Change, By Agreement or Decree

Cleveland has been at the center of a policing tactic debate for years, but now, due to intervention by the Department of Justice, the city is starting to see progress

In the past decade, America’s newsfeed has been flooded with stories of police brutality — and questions about lack of accountability officers usually face.

A 2015 Washington Post and Bowling Green State University analysis found that from 2005-2015, only 54 police officers across the country were charged for fatally shooting someone, despite thousands of such shootings during the same period. These shootings, sometimes documented by body cams or witnesses’ smartphones, cause some people to fear the police.

Senior Grace Farrell recalled a time earlier this fall when she was in the car with her mother and was pulled over by a Shaker police officer. Farrell, who is African-American, said she thought during the incident, “Me and my mom are about to die in two seconds, and I don’t know what’s going to happen. I don’t know how to get through any of this. I don’t know if anyone’s going to help us, or if this is going to be another situation where nobody is going to do anything about it.”

Farrell said that everything turned out alright because they were only pulled over for a broken taillight. The officer was courteous, she said. But the situation was nerve-racking, she said, because she didn’t know if she and her mom were being pulled over for a legitimate reason, or if it was because of her skin color.

In the past few years, stories of the violent deaths of young African-Americans, mostly men, at the hands of police have dominated the internet, incited protests and inspired the creation of social justice movements and organizations.

One of the most notable protests occurred in Ferguson, Mo. after a white police officer shot and killed Michael Brown Jr., an unarmed African-American teenager. Protests against police brutality ensued in Ferguson and turned violent as people looted businesses and destroyed buildings in August 2014. Police responded by firing tear gas, smoke bombs and rubber bullets.

Calls for accountability and reform are mounting. Campaign Zero is an organization committed to ending police violence and reforming policing policies. By examining police contracts, they aim to stop the incidents that caused Farrell to feel the way she did when she was pulled over.

To do this, the organization created six categories and used them to evaluate police contracts across the country for the ways that they limit police officer accountability.

The organization attempted to review the police contracts of the 100 largest U.S. cities. They were able to evaluate 81 contracts, including Cleveland’s. Three of the 100 cities do not have police contracts, and the remaining 16 refused to send their contracts in for evaluation.

The first category is disqualifying misconduct complaints. For example, if someone submits a complaint about a police officer, provisions within the police contract may disqualify or invalidate the complaint if it is not submitted within a certain period of time after the incident occurred. Twenty-six of the 81 contracts Campaign Zero reviewed contained language that disqualified misconduct complaints.

The second category is restricting interrogations of police officers. For example, a contract may prevent a police officer from being interrogated within 48 hours after an incident occurs. This waiting period can prevent the entire story from being told, and it can decrease the effectiveness of an investigation.

Fifty police contracts Campaign Zero reviewed contained provisions that restricted interrogations.

Giving officers unfair access to information is the third category. Forty-one contracts Campaign Zero evaluated allow police officers to see information before they are interrogated about an incident. Civilian suspects do not have such access. In 16 cities, officers are allowed to review all of the evidence against them prior to the interrogation.

The fourth category is limiting discipline and oversight. A violation in this category can include preventing a police officer’s past history of misconduct from being considered in a future investigation of them. Limiting oversight can also prevent the media from holding police officers accountable by preventing the release of information about an officer under investigation. This is the most common violation, found in 66 of the 81 contracts.

The fifth category is requiring the city to pay costs related to police misconduct. Violations under this category may require cities to give officers paid leave while under investigation, to pay legal fees related to their actions or to pay citizens when the police reach a settlement, the organization wrote. Campaign Zero found 41 contracts contained violations in this category.

The sixth category is erasing misconduct records. These violations can include removing complaints from an officer’s personnel file or erasing all records of misconduct after a certain period of time upon request. Forty-three cities’ contracts contained violations in this category.

Out of the 81 contracts reviewed, 73 contained at least one of the six violations. The most common violation was limiting discipline and oversight, and the least common was disqualifying misconduct complaints.

“Police unions have used their influence to establish unfair protections for police officers in their contracts with local, state and federal government and in statewide Law Enforcement Officers’ Bills of Rights. These provisions create one set of rules for police and another for civilians, and make it difficult for police chiefs or civilian oversight structures to punish police officers who are unfit to serve,” the Campaign Zero website states.

Campaign Zero found that the Cleveland Division of Police contract contained violations in five categories. The only exception was requiring the city to pay for officer misconduct.

That means that if a Cleveland police officer is suspended during an investigation, the City of Cleveland is not required to pay the officer’s salary.

Police contracts that include such language can limit how strictly police officers are held accountable for misconduct, including shootings. Such limits can, in turn, affect how a police department performs and is perceived within its community, according to Campaign Zero.

But Commander John Cole of the Shaker Heights Police Department does not think that contracts limit police accountability.

He said that a contract is used to ensure that a police department follows its own rules when disciplining or terminating an officer and that officers will always be held accountable for their actions.

¨I can’t speak to anyone’s intention,” said Ayesha Bell Hardaway, an assistant professor of law at Case Western Reserve University Law School and a member of the Shaker Heights City Schools Board of Education. She continued, “I would imagine [police unions] have come up with things that they think will make their jobs less onerous or more friendly to their interests. And I think that is very much intentional, to create a document that is friendly, puts forth the interest of the union members,” Hardaway said.

However, amending features of police contracts isn’t an easy task because contracts are negotiated between the city that employs the police and the union that represents the police officers.

From the view of a police officer or a union representative, provisions that end up limiting accountability can be seen as ordinary contract features. Hardaway said that such limiting provisions exist within the contracts of many jurisdictions.

“Typically, when there’s a provision in a contract, it doesn’t just change. If the union contract spans for two years or three years, when it’s up for renegotiation, there has to be some sort of impetus that would cause the city to want to change it,” Hardaway said. Because of the nature of negotiations, Hardaway said, the city would have to give something up in order to remove or change a provision.

Further challenges in negotiating police contracts include the need to protect officers. “There’s this balance, of course, between making sure that the officers have due process, but then being sure that there’s the opportunity to explore other solutions that don’t just serve to completely obstruct the accountability processes,” Hardaway said.

When officers have due process, it means they are treated fairly when they are accused of wrongdoing. For example, if an officer is accused of excessive use of force, the claim will be investigated and the officer given a chance to explain their actions.

Cole said that union contracts help to protect police officers because they do not have the right to strike in Ohio. Contracts are beneficial, he said, because they outline the expectations between management and employees.

Although removing the limitations from police contracts can happen, it is unlikely that these provisions would ever be removed all at once through negotiation.

“In the context of reform efforts aimed at remedying a pattern or practice of unconstitutional policing, consent decrees have been viewed as the best way to provide numerous levels of support to struggling police departments, including in the revision of policies,” Hardaway said.

Often at the request of an elected official, the U.S. Department of Justice will investigate a police department for unconstitutional policing, often leading to the adoption of a consent decree, which is an agreement to resolve a dispute between two parties. Investigations and the adoption of consent decrees have proven effective.

“One frequently cited success story is Seattle, where a 2012 consent decree has been credited with reducing unnecessary uses of force and improving citizens’ trust in officers,” The New York Times reported. Hardaway said that the Seattle police officers started to use body cameras because of the consent decree.

The DOJ investigated the Cleveland Division of Police and released its report Dec. 4, 2014, citing a pattern of “unreasonable and unnecessary use of force.”

According to The New York Times, the DOJ began the investigation into CDP practices at the request of Cleveland Mayor Frank G. Jackson in 2013.

Jackson’s request came after Cleveland police officers killed two unarmed African-Americans after their car backfired Nov. 29, 2012. Police mistook the sound for gun shots and began a 20-mile chase that grew to involve 62 police cars. The chase ended when the civilians pulled into a parking lot and officers fired 137 rounds into their vehicle at close range, killing both passengers.

The DOJ investigation was announced two weeks after a white Cleveland police officer shot and killed Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old African-American boy, in a Cleveland park Nov. 22, 2014. Police had responded to a report of a man who was pointing a pistol at random people in a park. During the call to the police, the caller said that the gun was “probably fake” and that Rice was “probably a juvenile.” The weapon was a realistic toy gun known as an AirSoft pistol.

Rice’s death made national news as part of the increasing trend of unarmed African-American males killed by police.

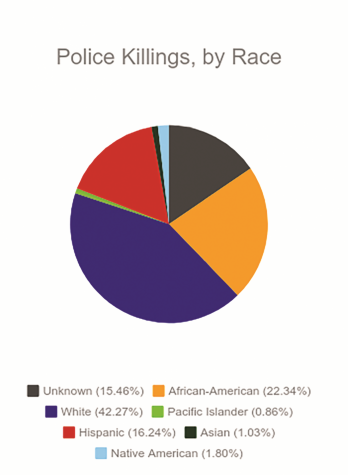

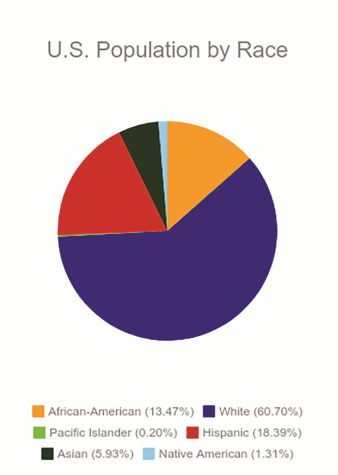

Police officers killed 1,164 people across the country in 2018. African-American people were 38 percent of those killed by these 100 police departments, despite comprising only 21 percent of the population in their jurisdictions, according to Mapping Police Violence.

Instances such as Rice’s death and the car chase led the NYT to deem the CDP “synonymous with the racially charged debate over police tactics” in a 2015 article.

The DOJ’s report found that Cleveland police officers used excessive force with firearms, tasers, chemical sprays and fists.

“The report also said the police had used excessive force against mentally ill people and employed tactics that escalated potentially nonviolent encounters into dangerous confrontations,” according to the NYT.

Cleveland worked with the DOJ to address abuses found in the report and to create an improved division of police. This cooperation resulted in the creation of a consent decree.

“What is remarkable, though, about Cleveland and this agreement is that it reflects the decision of community members, law enforcement, leaders and city officials to do the difficult work that is required to address systemic issues that can undermine cooperation between police and large parts of the community, and thereby reduce public safety for all of us,” said Vanita Gupta, former head of the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division, May 26, 2015 at the announcement of the consent decree.

“What is remarkable, though, about Cleveland and this agreement is that it reflects the decision of community members, law enforcement, leaders and city officials to do the difficult work that is required to address systemic issues that can undermine cooperation between police and large parts of the community, and thereby reduce public safety for all of us,” said Vanita Gupta, former head of the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division, May 26, 2015 at the announcement of the consent decree.

“With this agreement, the city and division of police agree to implement comprehensive reforms in the way that the CDP recruits, selects, guides, trains, supervises, investigates and disciplines officers to ensure that officers are practicing constitutional, community-oriented policing, and that those officers who fall short of that standard are held accountable,” Gupta said.

Agreements made in the consent decree are based on reforming policing practices. The consent decree requires that the CDP create plans that reform staffing, recruitment and develop a community and problem-oriented policing plan.

The CDP agreed to document every time an officer unholsters their gun, and supervisors are now required to investigate instances of excessive force the same way that crimes are investigated.

Cleveland police officers, abiding by the consent decree, are prohibited from using force in response to someone talking back or running away. Pistol whipping and firing warning shots are also prohibited in the agreement, according to the NYT.

Officers are now required to self-report instances of excessive force, and the officers’ personal reports are compared to internal reports that record every time a stun gun is used.

The new agreement prohibits shooting from moving cars, a guideline that policing specialists have called for across the country, and has proven effective, according to the NYT.

The new agreement prohibits shooting from moving cars, a guideline that policing specialists have called for across the country, and has proven effective, according to the NYT.

When the New York Police Department put this rule into place in 1972, the number of people killed by police dropped by 37 percent, and half as many officers were killed in the line of duty, according to The Guardian. “Between 1972 and 2010, the number of incidents each year involving an NYPD officer firing his or her gun dropped from 944 to 92,” The Guardian wrote.

The consent decree also established the Cleveland Police Monitoring Team, which plays the roles of arbitrator, adviser and facilitator in monitoring how the CDP implements the agreement and how this implementation results in effective and constitutional policing.

“This means that the Monitor reviews, provides feedback on, and ultimately recommends approval or disapproval to the court of changes in policy, training, procedure, and other practices within the Division of Police,” according to the Monitoring Team.

Hardaway is a member of the team. “We’re just considered subject-matter experts who serve as agents of the federal court to work with the [DOJ] and the local government, in this case the City of Cleveland, to work through the implementation of the consent decree terms.”

Hardaway said that the monitor has had no direct role in negotiations of Cleveland’s police contract.

The consent decree also created the Cleveland Community Police Commission. Choir teacher Mario Clopton-Zymler is a member. “The Commission is a group of 10 civilian community members and three police representatives from the three police organizations in Cleveland. The commission civilians and police officers have a great working relationship. We work on policy changes and leverage our community connections to bring feedback into the reform process,” Clopton-Zymler said.

When the commission was announced in May 2015, Clopton-Zymler applied and was sworn in September of that year. He said he was inspired to get involved after Rice was killed.

“He was 12 years old, and at the time I was teaching middle school students his age. I couldn’t imagine what it was like to have experienced one of your students being killed so tragically,” Clopton-Zymler said.

The City of Cleveland has not yet completed all of the reforms mandated by the consent decree, but the city has seen improvements. “A report this summer on Cleveland’s continuing reforms cited a nearly 40 percent drop in officers’ use of force from the previous year,” according to the New York Times.

“The work of achieving bias-free community problem-oriented policing is ever changing, and ongoing,” Clopton-Zymler said. “I can say in Cleveland, through the reforms required by the consent decree that the division of police continues to make progress in those two areas of police policy with recommendations from the commission on both bias-free policing and community problem-oriented policing.”

The Shaker Heights Police contract includes one of the provisions Campaign Zero evaluated. “Oral and written reprimands shall, upon written request to the Chief of Police, be removed from the employee’s personnel file after a retention period of three years.

Any Internal Affairs investigations that do not result in a ‘sustained’ finding will not be placed in the affected employee’s personnel file,” the contract states. This language falls into the fourth category of limiting discipline and oversight.

“The reason that’s problematic is because it prevents the mapping of patterns of engagement of particular officers in certain geographical locations of a city with certain demographics of people,” Kevin LaMonica (’19) said.

But Cole stated that police union contracts do not limit accountability. In the case of the provision that allows the removal of reprimands, “the benefit to the officer could be that those complaints that are not sustained after investigation would not be in their personnel file for review by another potential employer and/or otherwise limit the officer’s ability to be promoted. The time frame benefits the officer through the removal of negative writings in their personnel files,” Cole wrote.

Even though the Shaker contract contains this provision, Farrell said that she feels comfortable around Shaker police officers because she saw them work in Safety Town, an educational program for children that teaches safety awareness.

“I feel like when I step out in the real world, it will be a little different because I feel [police officers] kind of have a bias towards black people,” Farrell said. “But in Shaker, I’m fine because I know some of them, and I know that they have good intentions.”

LaMonica, who was a CORE leader in the Student Group on Race Relations, attends Johns Hopkins University and is passionate about social justice.

He said that he knows a lot of people who are concerned about racial justice and reducing police brutality and that he thinks being aware of the impact of police union contracts is important.

“I just think regardless of where you are or what your community looks like, officers should be held accountable because they aren’t above the law,” he said.

He continued, “Shaker is kind of known for being on the forefront of race relations. There’s like three documentaries about Shaker integrating in the ’60s and ’70s. SGORR made national headlines for being one of the first student organizations of its time in the country that really focused on bridging divides based on race.

So who’s to say Shaker can’t be in the forefront of creating fair police policies?”

Comment using your Facebook, Yahoo, AOL or Hotmail account

Keith Oliver | Jun 9, 2020 at 9:32 pm

Excellent article. Very comprehensive. I’d like to add that a civilian oversight office was created as a result of the consent decree. The Office of Professional Standards (OPS) investigates allegations of police misconduct against Cleveland Police Officers. Anyone who witnesses or is involved in police misconduct may file a complaint with OPS. Complaints are fully investigated and include a mandatory officer interview that is video-recorded. Please spread the word as this office is effective but little-known.