Shooting Prevention, Not Paranoia

We must act to prevent gun violence through government action, rather than focusing on the stereotypes associated with shooters

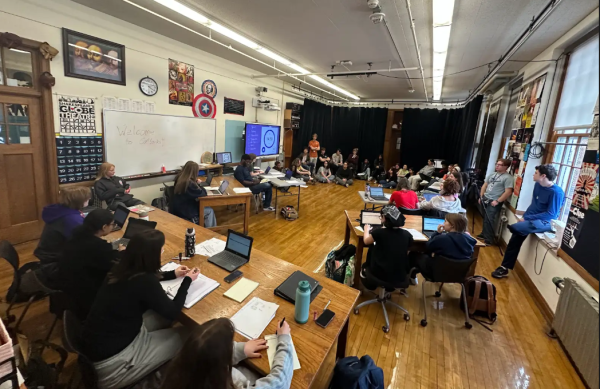

A still from a PSA released by Sandy Hook Promise about the importance of knowing the signs one may exhibit while planning a shooting.

A high school boy named Evan is communicating with an anonymous person by writing messages on a desk in the library. They communicate for days until finally he asks for a name, but when he comes back to check for a response, the library is closed for the summer.

When Evan is signing a girl’s yearbook later that day, her friend notices the handwriting and asks if he was the boy writing on the desk. They all laugh and start to talk about it when the gym door flies open, and in walks a boy who pulls out a rifle and cocks it as screaming, terrified students flee the gym.

This dramatization, which appeared in social media feeds in December as a public service announcement video, was released by Sandy Hook Promise, an organization that strives to raise awareness about the signs that a student may exhibit while contemplating a shooting. After the gym scene, the video revisits the earlier scenes and, through alternative camera angles, slowly reveals that the shooter was in the background all the while — being bullied or worshiping guns or avoiding social interaction. The video suggests that knowing these signs could help prevent another mass shooting.

And prevention is a noble goal. Every day in the United States, 314 people are shot. Of those, 41 are younger than 18, according to Sandy Hook Promise.

The organization’s website states that students who commit shootings could be victims of long-term bullying and may demonstrate feelings of persecution. Other signs could be an infatuation with firearms and mass shootings as well as “gestures of violence and low commitment or aspirations toward school, or sudden change in academic performance.”

Sandy Hook Promise clarifies that, “It’s important to know that one warning sign on its own does not mean a person is planning an act of violence. But when many connected or cumulative signs are observed over a period of time, it could mean that the person is heading down a pathway towards violence or self-harm.”

The video tricks us into feeling horrible for not noticing the signs of a distressed student, but then the organization says that people who exhibit these signs may not even be school shooters. This is paradoxical. The weight is on our shoulders to examine our classmates. Yet, clues we are to notice may not be evidence of danger.

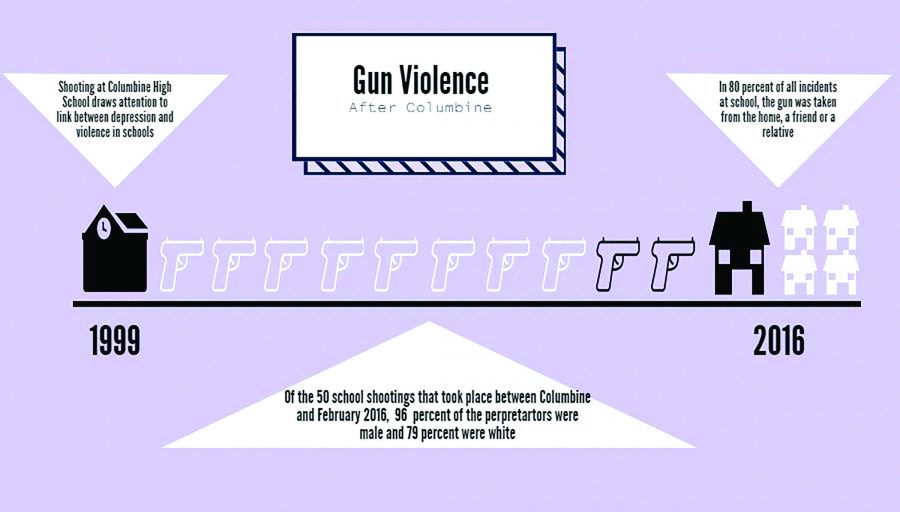

Since the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado, the stereotype that depressed teens are a danger to others has become prevalent in media. Previously, however, it was predominantly feared that a depressed student would inflict harm onto themselves.

In one of the worst school shootings in America, two Columbine seniors, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, killed 13 students and teachers and injured 20 others before shooting themselves. The Columbine shooting is credited for galvanizing schools to prevent similar incidents. Schools started to enact zero tolerance policies in an effort to decrease violence. This effort eliminated the decision that school officials had to make when deciding who is dangerous and who’s accidentally breaking the rules, according to “The Columbine Effect,” an article published in TIME Magazine.

In 2005, the Ohio general assembly introduced State House Bill 422, which implemented lockdown drills in schools. It was approved in 2006. Now, Ohio students practice three times a year.

It’s important to note that Columbine was the turning point, after which the media, school administrators, and psychologists identified a link between depression and violence toward one’s peers. The same TIME article reported on a student who was disciplined for sporting blue hair because the color was seen as “an omen of antisocial, possibly even violent behavior.” Expressing yourself through hair color now has become intertwined with being goth, and it’s a common stereotype that goth students are more likely to be violent.

“There is this view that an emo person is unstable and can hurt a lot of people,” junior Brian Ford said. This stereotype has evolved into what it is now: the lonely, bullied, goth white boy who sits alone in the cafeteria, loves guns, and is going to shoot up the school if people don’t leave him alone.

The Sandy Hook Promise organization relied on this image when it released the PSA about Evan, who was too focused on a mystery girl to notice that a lonely, bullied, goth white boy who sits alone in the cafeteria and is infatuated with guns was planning a shooting.

“I feel as though it is just that most school shootings that are shown in the news, the shooter is more often than not, white and a boy,” Ford said.

In truth, according to ABC news, of the 50 shootings that took place between Columbine and February 2016, 96 percent of the shooters were male. And according to Political Research Associates, 79 percent of the perpetrators were white. These numbers are the reason for the stereotype that has now become so well known.

Ironically, due to these statistics, white teenage males could be victims of a stereotype. They now must watch their appearance and behavior at school, as they could be perceived as a potential shooter if bullied. How the tables have turned.

Since Columbine, the rise of the internet has brought more and more attention to school shooting and shooters. Coverage of these incidents may make the idea attractive to potential shooters, who

feel attacked by their peers and want to be remembered.

“There have been school shootings and school bombings dating back to the early 1900’s, except now it’s in the media more so it gets shared on Facebook and Twitter, and everything gets retweeted and reposted,” school psychologist Sagar Patel said.

Patel said that this sensationalization of bombings on the news can lead to copycat incidents. He listed the Virginia Tech shooting as an example. The perpetrator emailed videos to news organizations before killing himself and 32 others.

“Then a couple days later, when the news stations got those tapes, they played them all over the news,” said Patel, “and that’s when the American Psychological Association stood up and said you need to get these off the air right now.”

The entertainment industry contributes, too. Hollywood produces crime TV shows by the dozens, and shooting games have captivated adolescents for decades. Violence is glorified in games such as “Call Of Duty,” where players are trained how to shoot to kill, and killing is normalized on shows such as “How To Get Away With Murder.”

Before society was surrounded by this glorification of violence, a troubled student may not have lashed out at others. But now the idea of mass murder has been planted in their brains by inescapable messages and images.

So Hollywood continues to profit from violence, and Congressmen continue to reap donations for refusing to regulate semi-automatic weapons. The only solution to mass shootings at school, then, is for teenagers to be suspicious of lonely classmates? There’s more solutions to the gun problem than “See something, say something.”

We should do something about the heart of the problem: guns. Adults in positions of power should put a stop to gun violence instead of putting the weight of prevention on struggling adolescents.

The problem that arises with the ‘if you see something, say something’ rule, is that it’s unclear what’s a joke and what’s not on social media.

According to Sandy Hook Promise, the shooter expressed his intentions in four out of five cases, which includes unreported threats on social media. If people want real threats to be reported, they shouldn’t post their gun violence jokes on social media.

“I think social media has made the lines blurrier because people can’t tell whether a picture of gun or a statement is serious or just for attention,” said junior Meredith Modlin.

Of course, in the case of a blatant tweet or an Instagram post of a selfie with a gun captioned, “See you at school,” students should notify adults.

But are we really responsible for noticing a classmate reading a catalog about guns? If we do notice, what must we do? Turn him in for reading?

It’s easy in hindsight to say, “Oh, Johnny read about guns and sat alone in the cafeteria. That was obviously a sign. I can’t believe we didn’t notice!” But people have their own lives and problems to face. With their own school work to complete must they simultaneously monitor what other students are researching? This is too much to ask of already stressed students.

Implementing tighter gun laws seems easier than expecting students to become amateur detectives. According to Sandy Hook Promise, in 80 percent of all school shootings, the gun belonged to a friend or relative and was taken from the home. In addition, “Approximately half of all gun owners don’t lock up their guns in their homes, including 40 percent of households with kids under age 18.”

It should never be this easy for a student to get a gun.

We need fewer unstable people with access to semi-automatic weapons, not more. Congress has persisted in defense of the second amendment, nevertheless. According to USA today, the Senate voted Feb. 8 to “overturn a rule barring gun ownership for some who have been deemed mentally impaired.”

I wish that America would act to prevent gun violence rather than just look for signs of a threat. But if the slaughter of 27 elementary school students and teachers at Sandy Hook Elementary wasn’t enough to change the minds of Congress about guns, what will?

Lifestyle Editor Maggie Spielman contributed reporting.