Further Than The Eye Can See

Diversfying Diversity series reinforces Shaker’s reputation for acceptance while acknowledging opportunities for growth

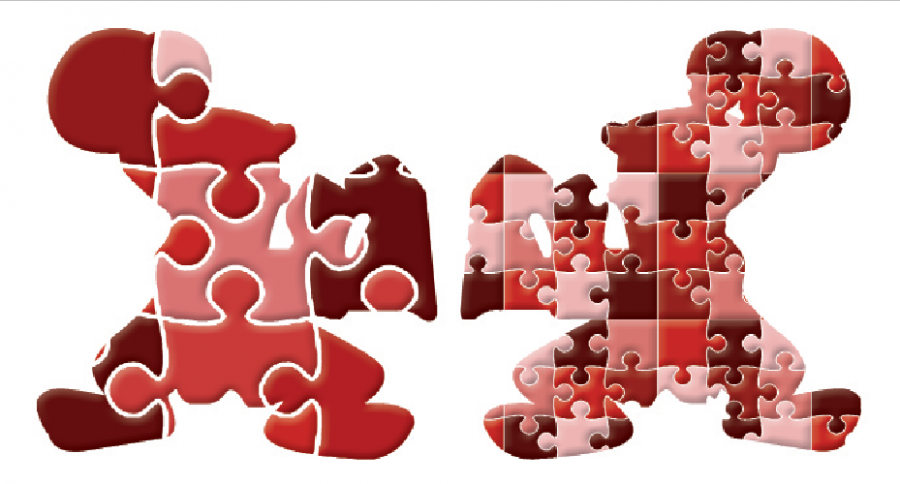

The Shaker Raiders display the different ways people can view diversity. The Raider on the left, divided into larger pieces, represents a view of diversity defined by traditional categories. The Raider on the right — divided into many more pieces — represents diversity beyond racial limitations.

There are more than one thousand students at Shaker, but not all of these students interact with one another or even know each other’s names.

“You walk the same way to your classes every day, and you see the same people every day in the halls, so you kind of create your own little school of faces,” Senior Evan Shaw said in an interview for the Investigations series Diversifying Diversity.

Though on paper Shaker appears to be a diverse high school, once inside, students segregate themselves, and this separation results in a less cohesive school.

Shaker events are just one example of this division.

Productions like Sankofa that celebrate minority cultures give the student body an opportunity to expose themselves to ideas different from their own, but the attendees do not represent the student body either.

“Is it the best representation of Shaker? No. Is it Sankofa’s fault? Absolutely not,” Stage Crew Leader Lauren Holloway said. “People choose whether they want to show up or not it just happens to be more of the African American community within Shaker Heights. Would it be nice to see a mass crowd with different backgrounds? Of course. Will it ever happen? Who knows?”

Some organizations like SGORR, for example, are racially diverse, but that diversity is somewhat forced.

“It’s 100 percent a flawed and hypocritical system,” Core Leader Nat Crowley said, “which we as an organization understand. But ultimately, it is the only way that we can ensure that we have a diverse organization, which we feel is important since we are trying to promote diversity and improved race relations.

“Every year, we admit 15 white males, 15 white females, 15 minority males, and 15 minority females,” he continued. “This we feel is justified, because we aren’t admitting under-qualified applicants simply to fill a quota, but we think that we have enough passionate and capable students to fill all of these slots each year.”

Crowley admitted that a critique of the “discriminatory acceptance” admission into the program is also justifiable. “However,” he said, “it is the only way to ensure that we are admitting a diverse group of students in order to foster better discussions with different viewpoints as well as leading by example as we are promoting improvements in race and human relations.”

SGORR’s admissions process is not only “flawed,” it’s inaccurate. 52 percent of students at Shaker are African-American, 37 percent Caucasian, 5 percent multi-racial, 3 percent Asian and 2 percent Hispanic, according to the factbook on the district website.

Were SGORR to actually represent Shaker’s student body, it would admit 31 African-American students, 23 Caucasian students, three multi-racial students, two Asian students and one Hispanic student each year in order to mimic the district’s statistics.

The theory behind racial quotas is, as stated by Crowley, to represent the viewpoints of all members of the student body. Yet racial quotas capture only surface-level differences, and so often end up accidentally excluding students whose identities are not immediately visible.

For example, a student’s religion, sexual orientation or gender identity may be represented in some years’ crop of recruits and overlooked in others, yet these aspects play an important role in a student’s experiences.

In an interview for Diversifying Diversity, senior Martha Jackson and junior Sheila Scanlon provided an example.

“Mario Clopton, our choir director, has from day one been open and accepting and has said, ‘Hey listen, guys, you are gonna respect everyone’s pronouns, this is a safe environment for LGBT kids,’ because he’s an openly out LGBT man and from day one he has always used my pronouns in choir,” Jackson said.

“He’s the only teacher I’ve experienced who’s come forward and said all gender identities are welcome and we’re gonna respect everybody, and the only teacher who openly asked what people’s pronouns are and then used them,” they continued. “None of my other teachers have ever asked what anybody’s pronouns are.”

“It’s the whole community thing,” Scanlon added. “You want to be with a group of people who may not be the same as you, but have the same experiences and who get it and who aren’t going to invalidate your experiences.”

This ‘invisible diversity’ doesn’t only affect students’ social and mental state, but also the practicalities of day-to-day life at the high school.

“Our spring breaks always correlated with Passover,” said Shaw, who attended the Joseph and Florence Mandel Jewish Day School prior to transferring to Shaker in ninth grade. “And now, sometimes they do, and that’s convenient, like we don’t have to bring Matzoh to school, but sometimes they don’t. And that’s like, whatever, that’s just life.

“It’s hard when you’re non-binary, because, like, what bathroom do you use?” Scanlon asked. “I use the women’s restrooms, because the other alternative would be to go to the nurse every time I want to go to the bathroom.

“I need to go to the bathroom too many times in the day to go down to the nurse’s office every single time. If you’re trans, you can get – I think it’s called a permanent pass to go down to the nurse’s office to go to the bathroom, so there’s that. [But] that singles us out. We have to go to the nurse. We have to go do this, or whatever.”

At Shaker, students often find themselves facing not prejudice, but ignorance; because of the limitations on the current definition of diversity, the burden falls to minority students to represent and, sometimes, defend themselves.

“Even though my pronouns are on my Instagram and I put my pronouns everywhere, people still don’t really use them,” Scanlon said.

“Shaker is pretty open and tolerant but it’s still not everyone, a lot of people still have misconceptions and stereotypes and they still have a negative view of trans and gay people,” they said. “Even if it’s not an expressed hatred it’s still bias, a negative connotation.”

“The principal said to the teachers that for hijabs it’s ok,” sophomore Arwa Elmashae said, regarding dress code and the rule prohibiting “headwear” in school, except for religious purposes.

“But some people say, ‘Why are they wearing hijabs, it’s the same as us wearing hats’ – and it’s not. It’s like, you wear a hat because you really want it, and you wear a hijab because it’s part of your religion,” Elmashae explained.

“I try to explain, and then the next time I try to explain, and it’s like ‘Why are you doing this, why are you doing this’ and sometimes I get tired of explaining each time,” she said.

Students like Shaw, who do not encounter as much friction, however, don’t feel the same exasperation with their fellow students.

“I get questions pretty often about Judaism, and like, they’re usually good questions,” Shaw said. “Someone’s like, ‘I don’t want to sound ignorant,’ but no! I would always rather someone ask a question, than just hold their assumptions.”

Assistant Principal Kathleen Sauline believes it is important that Shaker continues to hold discussions on cultural and diversity awareness, especially at the high school.

“We want those conversations to go on here, and I think it’s best that they’re student led,” she said.

“So someone could ask a question, but they’d do it with the proper background knowledge,” Sauline continued.

Said Elmashae, “Here in Shaker it’s all like, we should respect each other, [even] if someone is different than others.”