Go Well, Madiba

English teacher Elizabeth Colquitt, who has spent time in South Africa, reflects on Nelson Mandela’s life and passing

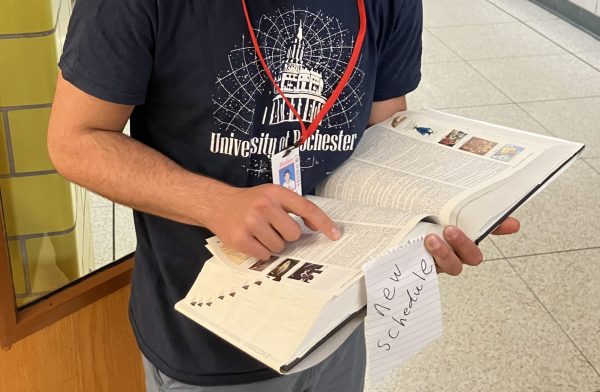

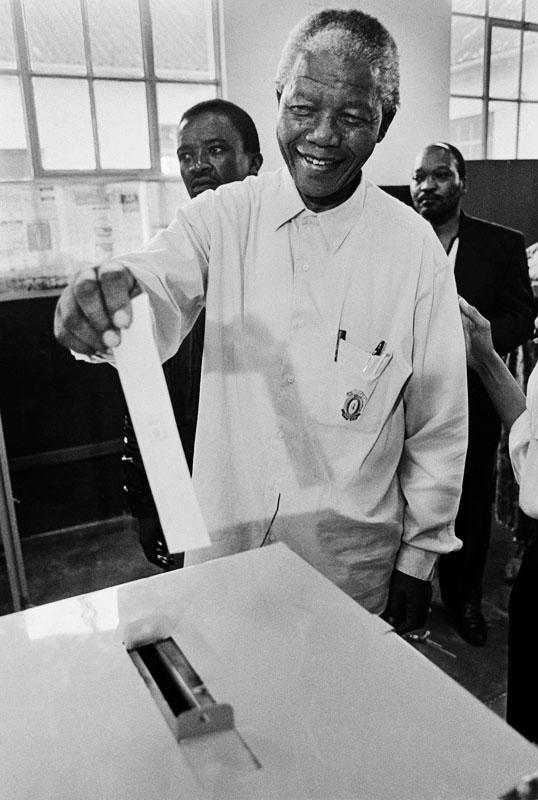

Nelson Mandela visits the London School of Economics in 2000. Mandela died Dec. 5. He was 95.

I knew this was coming: he was 95, after all. But it surprised me that I reacted so strongly. Nelson Mandela has been in and out of the hospital all year, and I assumed the image on TV indicated another flare-up – until CNN followed that picture with another, and another, and another. Next FOX, then MSNBC switched from late-afternoon programming to breaking news. My breath caught, knowing that this kind of media coverage only follows death, and my eyes began to fill up.

I first encountered the racist apartheid system that Nelson Mandela worked so hard to conquer in college. As I crossed campus my freshman year, I saw in front of the graduate library a wooden shanty, painted brightly with “U.S.A. out of South Africa” and “Free Nelson Mandela” slogans. It sat there for three years. Occasionally the administration dismantled the shanty, since the University of Michigan had significant investments in South Africa, but students always promptly rebuilt and repainted it. I can’t say that my 20 year-old self fully grasped the significance of the protest, but that shanty disappeared for good in 1990, the year Nelson Mandela walked out of the prisons that had been his home for the previous 27.

My infatuation with South Africa began with Bryce Courtenay’s breathtaking descriptions of the country in my favorite novel, The Power of One. I longed to walk the hills and explore the kloofs with his larger-than-life hero, Peekay. In Cry the Beloved Country, a novel I teach in 11th grade English every year, Alan Paton’s poetic prose also pays homage to South Africa’s stunning landscapes and gorgeously printed animals, while mourning its racism and violence. Violence and beauty provide the backdrop for Nelson Mandela’s story.

Mandela displayed a saintly ability to work and make peace with his oppressors, yet his actions were not just inspiring; they were clever, deliberate and designed for political effect. As president, he flew out to have tea with the widow of Hendrik Verwoerd, the architect of apartheid. He invited his jailer from Victor Verster prison to his inauguration ceremony. Over and over he demonstrated the fair and forgiving behavior he hoped and expected to see in his countrymen. Nearby countries had descended into corruption, violence and chaos after the departure of colonial powers, and Mandela decided South Africa could do better. He put the full force of his legal experience, 27 years of prison education and personal charisma into convincing both whites and non-whites to follow a more productive route: reconciliation.

I admired Mandela as the rest of the world did, but I didn’t appreciate his political genius until I saw Clint Eastwood’s 2009 film “Invictus”. Mandela’s calculated support of the Springboks, a mediocre rugby team whose fan base was composed entirely of white South Africans, united the entire country behind their run at the 1995 Rugby World Cup.

I traveled to South Africa in the summer of 2009 to assist in livestock research on a private game reserve not far from Kruger National Park. While there, I asked the team leaders what they thought of the newly-elected President Jacob Zuma. He was no Mandela, they said, but they would wait and see. These twentysomething white South Africans insisted that their parents’ generation was racist, but they did not feel or endorse their parents’ sentiments. They didn’t see why everyone couldn’t just move on; 15 years had passed since South Africa had held the democratic elections that placed Nelson Mandela at the helm. As an American, I knew what a long, hard road South Africa faced. For once, I didn’t see my country as a clumsy, idealistic teenager on the world stage, but a country that knew from painful experience that 150 years was not enough to redress the injustices of centuries of brutal repression.

Two years ago, I persuaded the University of Cape Town to accept me as a graduate student for a semester. I immersed myself in the voices of African independence, including Mandela’s autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom. Again I admired Mandela’s clever exploitation of his symbolic status to keep his beloved country on a path towards racial harmony. My love of South Africa has not diminished after living there, but my concern for it has increased. I have never lived in a place so fearful or economically and racially divided. Crime plagues South Africans at every income level. The consequence of the stark inequality between those who live in townships and those who live in Johannesburg and Cape Town’s middle-class suburbs is the electronic gates, dogs and razor wire that protect every private residence.

My family and I took a township tour – a difficult but utterly memorable day in which we saw the poverty up close. We marveled at the friendliness of everyone we met. Why, my mother asked me, don’t they hate us? They have every reason to hate us. Yet they welcomed us, our tourist dollars and our embarrassed interest in their appalling living conditions, and if they felt resentment at seeing our white faces snooping into their lives, we never saw it.

On Friday morning, during Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s eulogy for his friend and compatriot, he joked about Mandela’s predilection for loudly printed shirts, but his worried question stuck with me: “What is going to happen to us? Now that our father has died?” Until last Thursday, South Africa had Mandela, the face of the aspiring Rainbow Nation, to remind them of their better selves. He still smiles down on South Africa from the sides of buildings and the thousands of murals that decorate the townships. There cannot be anyone in the world that has better earned his rest than Nelson Mandela, but I worry for the fragile rainbow that he left behind.