Speaking Up, Safely and Peacefully

Elevated political conflict sparks debates over student speech and a desire for discussion

Following the election of President Trump, political controversy ignited nationwide, as well as within the borders of Shaker Heights. Though Shaker has earned the label as a liberal “bubble,” the national divide is present here as well.

“We’re not in every way a microcosm of the nation at large,” said social studies and English teacher Halle Bauer, (‘06). “I do think we’ll probably see an intensification of political feeling.”

The expression “Shaker bubble” characterizes the school and community as overwhelmingly liberal. This homogeneity repels alternative views and influence, which then emboldens liberal intolerance of conservative ideas and speech. The bubble thus limits students’ exposure to and engagement with such ideas.

And without much practice listening and responding to students whose views contradict theirs, students can struggle to do so respectfully.

Alumna Sarah Tibbitts (‘16) explained that although she did not necessarily agree with Shaker’s label as a bubble, she acknowledged clear political differences between Shaker Heights and The Ohio State University, which she currently attends.

“I don’t think I knew a Trump supporter before coming to college,” she said. “Ohio State is a fairly politically active campus, and I would say there’s a liberal leaning. However, it is a state school in a traditionally red state, and I’ve seen way more ‘Lock her up’ and ‘Build the wall’ signs than I’m comfortable with.”

Tibbitts also acknowledged the intensity of the election. “In a normal election, I would enjoy the fact that coming to college has allowed me to meet people with views that challenge my own. I think I too often conflate being liberal with being open-minded, and I think it’s an important part of growing up to be able to expand my views,” she said. “But in this election, the politic was and still is very personal.”

Bauer said she did not shy away from political discussion in class despite this year’s intense and personal campaign. “I think we have to not embrace the conflict, but be open to talking about it. I think that’s the only way,” said Bauer. “If two people respect each other, they don’t have to share the same opinions, but that respect allows them to have a conversation that I think sometimes we shy away from, so I just hope that the conversations continue.”

“I think there’s something to learn and grow from when you have an honest dialogue,” Bauer added.

Principal Jonathan Kuehnle echoed this idea. “It is my belief that true learning happens when it’s a real-world, controversial topic and you’re able to explore and have those talks with each other and try to arrive at a place where we can all compromise, we can all agree, instead of just sniping at each other or saying how bad the other side is,” he said.

Kuehnle acknowledged the importance of teacher training to facilitate discussion.“A lot of it is up to how the teacher in charge of the classroom controls the classroom or manages the experience and ultimately guides the learning,” he said.

English teacher Cathy Lawlor taught Social Issues in Fiction and Nonfiction for more than 10 years. Lawlor said it was through this experience that she obtained the skills needed to facilitate a meaningful discussion in class.

Lawlor explained the importance of laying groundwork for the class at the beginning of the year. “I put a lot of thought into how I want to start out the year, and we spent a lot of time establishing rules of common decency. We actually had the whole first unit about civil discourse,” she said.

According to Kuehnle, civil discourse is also a key component of a curriculum employed by Facing History and Ourselves, a non-profit organization. According to its website, Facing History aims “to engage students of diverse backgrounds in an examination of racism, prejudice, and anti-Semitism in order to promote the development of a more humane and informed citizenry.”

According to the Facing History website, this guide tells teachers how to “create a reflective classroom, develop a classroom contract, provide opportunities for student reflection, establish a safe space for sensitive topics, implement teaching strategies that provide space for diverse viewpoints and encourage active, engaged listening.”

“Facing History-style lessons that I’ve observed in our building have gone very well and been very engaging for our students,” Kuehnle said. “We are actually providing training for our entire staff in the month of March.” Teachers will be trained in using a Facing History guide called “Fostering Civil Discourse.”

He explained that Facing History aids teachers in creating a safe environment for respectful and meaningful conversation. By adopting the curriculum, Kuehnle said teachers “can teach you how to respond, but in such a way that it’s conversational, and it may be spirited and passionate, but that’s fine — you’re working towards finding an eventual resolution or eventual agreement instead of just going at each other, instead of just fighting.”

According to Lawlor, another way to maintain a peaceful environment is by establishing class rules for discussion.

“We actually spend a couple of days just talking about what kind of ground rules we want in the class, and so it’s not just me, like, ‘These are the rules and you guys will follow them.’ It’s like, ‘What do you guys want to see? What do we want as far as creating a safe space and being able to talk about issues, and sometimes very controversial issues in a respectful way?’ ” she said.

Lawlor also requires students to offer evidence for their statements. “You have to work on teaching kids how to support their views,” she said. “They have to say, ‘Well, this is what I believe and this is why,’ and so that gets them used to the idea of having to support what they’re saying.”

“You’re requiring them to really think,” she added. “I think that takes away some of this danger of kids crossing into just spouting their opinions and turning hateful.”

However, even supported opinions may offend peers and lead to conflict in discussion; thus, limits of student speech have been widely debated.

The expression of student opinion in a public high school is largely protected under the First Amendment, which states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”

Students’ First Amendment rights have been solidified by Supreme Court cases such as the notorious Tinker v. Des Moines in 1969. The Supreme Court ruled that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

Despite this ruling, there are limits to student speech within a public high school, which have also been upheld by historical Supreme Court cases, such as Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser of 1986. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of punishment of a student who expressed a political opinion in a vulgar manner during an assembly.

Law Clerk Sarah Ingles of the Ohio American Civil Liberties Union acknowledged that limits to student speech in a public high school are circumstantial and are determined by the court.

“Students may express their opinions, even on controversial subjects, so long as it does not materially and substantially interfere with education and does not materially and substantially interfere with the rights of others,” Ingles said.

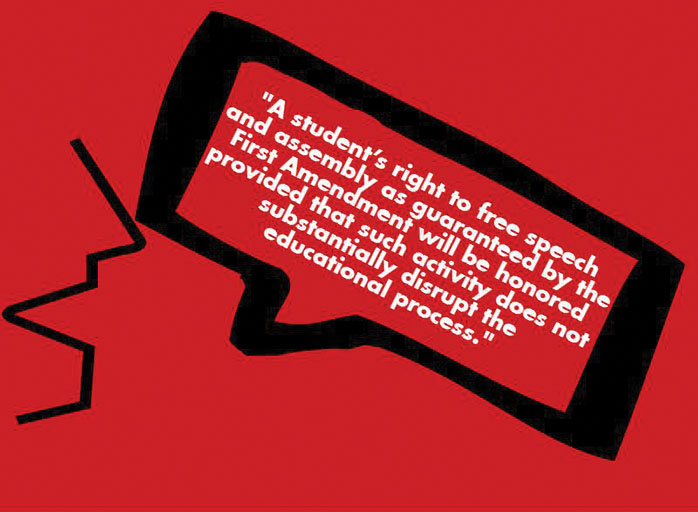

Shaker’s student handbook outlines the limits to students’ First Amendment rights. “A student’s right to free speech and assembly as guaranteed by the First Amendment will be honored provided that such activity does not substantially disrupt the educational process,” the rule states.

Asked to explain the specific grounds under which student speech is punishable, Kuehnle said, “It’s pretty open-ended. A lot of it would depend on the context of the situation. It just depends on the time and place and the details of the case.”

Controversy erupted at the high school during November over a social media incident in which two students displayed another student’s racially charged comments via Twitter. Both students were initially suspended by the district, sparking student protest.

The ACLU wrote the district a letter on behalf of one of the punished students, Myyah Husamadeen, which stated that “the ACLU of Ohio is gravely concerned that Shaker Heights High School student Myyah Husamadeen is about to be punished for exercising her First Amendment rights.”

The letter subsequently urged the district to revoke this punishment, and Husamadeen told The Shakerite that she was later offered an alternative punishment to the suspension.

“The interesting thing to note about the First Amendment is that it is not designed as a popularity contest, and instead must protect all views, including those that are less popular,” Ingles said.

“I think it would be sheltered and unrealistic of me to not ever want to hear the other side’s opinion,” said Tibbitts, “but when freedom of speech turns into hate speech — for example, ‘Build a wall,’ ‘Go back to where you came from,’ using the N-word or swastikas or degrading any person based on their historically oppressed gender, race, religion, etc., I think it crosses a line and is no longer acceptable.”

Hate speech, as defined by the American Bar Association, is “speech that offends, threatens, or insults groups, based on race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, disability, or other traits.”

Tibbitts added, “First Amendment rights are no excuse for bigotry.”

Student Group on Race Relations leader Izzy Wang also echoed this.“It is not conducive to our nation’s forward progress when people misuse their freedom of speech to perpetuate hate and fear,” she said.

As a teacher, Bauer acknowledged her role in monitoring student speech. “I think there’s a line when somebody’s feeling hurt, and it’s just my job as a teacher to make sure that line is not crossed. Free speech is one thing; harming another person is something else,” Bauer said.

Though Kuehnle acknowledged that consequences of crossing this line are situational, he emphasized the district’s recent implementation of a restorative justice program.

Kuehnle said the program allows students to acknowledge mistakes and correct them accordingly.

“We need to be about more than just consequences. We need to be about justice and moving forward and understanding,” he said. “[Students] may get a disciplinary consequence, but they’ll also get the opportunity to learn from it and to make it right, and that’s what restorative practice is all about — not just suspending somebody, but having them learn from it.”

Controversial discussion is not only facilitated by teachers, but by student leaders as well. SGORR leader Vishnu Kasturi explained how he conducts conversation with his fellow group members.

SGORR leaders, collectively known as CORE, are responsible for holding weekly meetings with their high school group members and facilitating activities on race and identity in fourth- and sixth-grade classrooms.

“In discussions, I try to bring my own opinions to the conversation and also try to play devil’s advocate,” Kasturi said. “Offering differing viewpoints forces my group to try and understand where others may be coming from and enhances their understanding of very complex issues.”

Wang stressed the importance of listening. “Listening is crucial in every conversation, but many people choose to speak and construct responses rather than to listen. If we can listen to others and develop an understanding about where they are coming from, then we can create beneficial discussions, better advocate for our own beliefs and work from our similarities to create unity within our community,” she said.

According to Kuehnle, SGORR will conduct a series of forums outside of school for community members. “In the upcoming couple of months you’re going to see additional conversations facilitated by SGORR for students, for staff, and then some stuff in the afternoons and evenings for parents and community members as well,” he said.

Kuehnle referenced a Nov. 16 SGORR discussion. “We wanted to provide more opportunities along the lines of like what SGORR did about a week or so after the election,” he said. “That went really well.”

The discussion focused on “stepping forward” and was held in the school’s lower cafeteria. The forum was structured in three phases. Phase one was about expression of emotion. Phase two covered our ideal community, and phase three was call to action.

Wang explained that the discussion was not centered around politics, but moving forward as a community. “We CORE Leaders did not specifically target politics,” she said. “We knew that, after the election, political discussion would be diverse because tensions ran high. Since we focused on building our community and uniting people of all backgrounds, I believe we were successful in facilitating a positive and practical discussion.”

Freshman Evan Grossman-McKee also said he believes forums are crucial to resolving conflict. “I have noticed elevated conflicts between students after the election,” said Grossman-McKee. “I think we can resolve this conflict by holding forums where people have a chance to share their opinions without being judged.”

“When you have a situation that’s this charged and this impactful, you can’t just say, ‘OK, we’ll have one meeting, we’ll have one conversation, everybody talked about it, now it’s great, we all get along.’ That’s not realistic. That’s not how it works,” Kuehnle said. “It has to be an ongoing, embedded, meaningful conversation.”

Journalism II reporters Jude Hinze-Gaines and Mae Nagusky contributed reporting.