Government Mandates Spawn New Non-Teaching Positions

“I probably couldn’t live without mine,” said Superintendent Gregory C. Hutchings, Jr. of his assistant. “She does all of my scheduling, she takes all of my phone calls, she proofreads all of my PowerPoint presentations, she uploads all of my BoardDocs.”

For most students, administrators blend into the background. They are the teachers’ bosses. They make the rules. Assistants, directors and supervisors clump together into a single category of non-teaching staff.

In the minds of those administrators, however, the distinctions are vast. Yes, those directors are administrators. No, their assistants aren’t. Yes, the treasurer is an administrator. No, his accounting specialists aren’t.

A Shaker administrator’s definition of administrators includes only those staff members with an administrative contract. By the district’s count, there are 35.

But that isn’t the full story. Another category of employees — including administrative assistants and specialists — fulfill administrative duties or help central administration fulfill theirs. Even though the work they are doing is under the administrative umbrella, these staff members are not on administrative contracts.

“There are people, like the instructional coaches, who are not in direct-contact teaching roles…They’re there to help other teachers improve curriculum delivery, but they are not in the classroom per se,” said Dr. John Morris, president of the Shaker Heights Teachers’ Association.

There are administrative assistants, who, as Superintendent Gregory C. Hutchings explained, “assist all of our administrators.”

“I probably couldn’t live without mine. She does all of my scheduling, she takes all of my phone calls, she proofreads all of my PowerPoint presentations, she uploads all of my BoardDocs. Those are administrative things that are taken care of by the administrative assistant,” he said.

There are coordinators — such as the International Baccalaureate coordinator. “A coordinator may not be classified as an administrator, meaning they aren’t on the administrative salary scale, but they may have some administrative responsibilities,” Hutchings said.

All these employees who do not carry the administrator title, yet still fulfill administrative duties, comprise another 38 staff members in the district and are considered “supervisor-administrators” by the district.

The definition of an administrator is often misunderstood or not agreed upon.

Assistant principals in Room 110 are counted as administration by the district; the other staff members in the room are not.

“If I am the administrative assistant to the principal,” Dr. Ben Scafidi, director of the Education Economics Center at Coles College of Business, wrote in an email interview, “then I am part of administration.”

Hutchings, however, said of his assistant, “No one would say she’s an administrator.”

“I think that administering something versus being an administrator are two different things,” he continued.

“Everyone,” said Bryan Christman, district treasurer, “has a different definition of an administrator.” For the purpose of this story, those employees whom the district considers administrators will be called such, and those who are merely administering something will be called supervisor-administrators

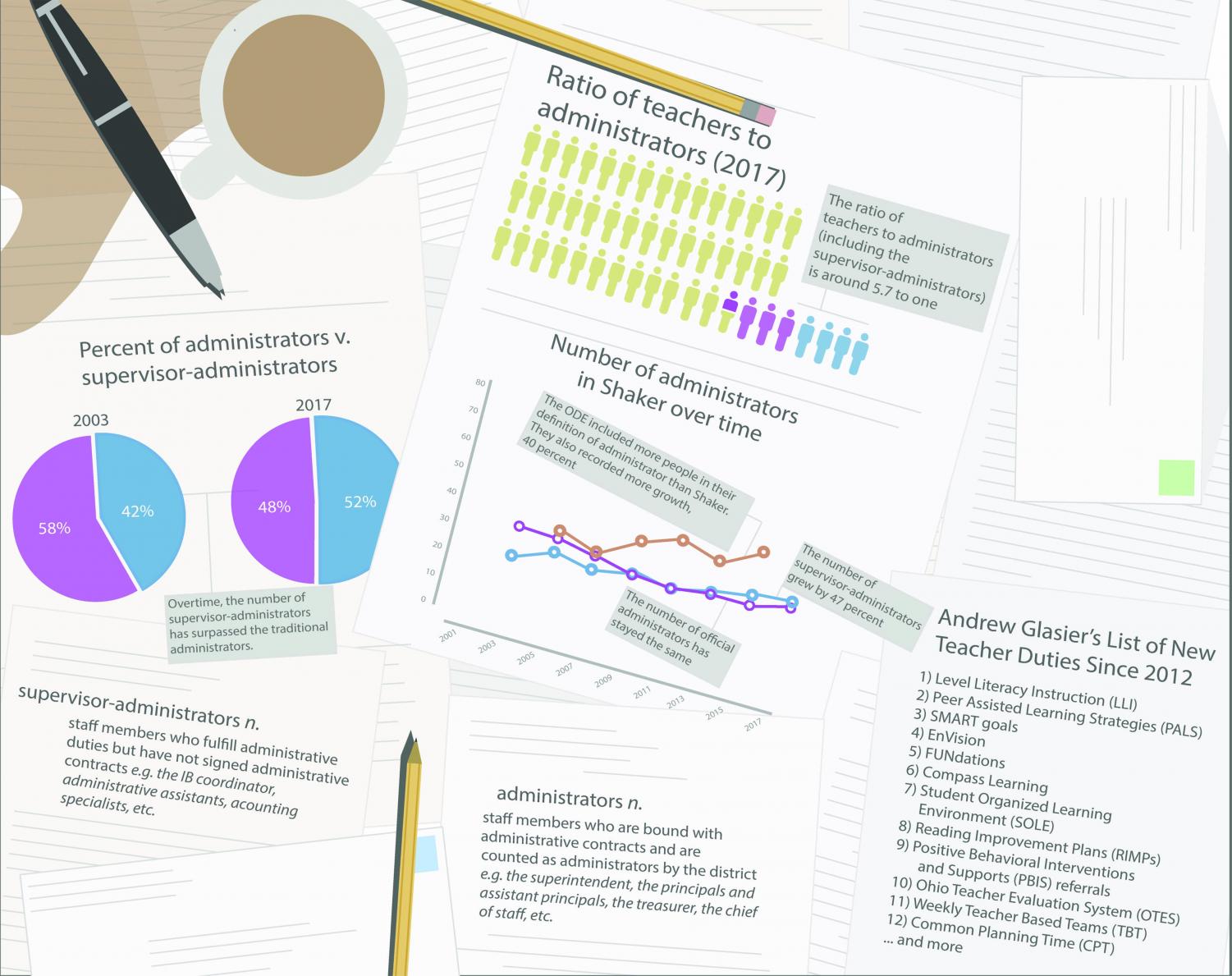

In addition to the number of administrators, there are two data points to consider. First, how many administrators there are per teacher. For example, If there were 73 administrators and one million teachers, that wouldn’t be very many administrators. Conversely, 73 administrators for only 50 teachers would probably be too many.

The second data point to consider is how much this ratio has changed over time.

According to the district, there are 11 teachers for every one of Shaker’s 35 administrators. This ratio has stayed relatively constant since 2003 — the earliest year for which records are available.

However, when the 38 supervisor-administrator positions that Shaker doesn’t count are included, this ratio drops to 5.7 teachers for every administrator. This seemed a little high to Scafidi, relative to the nationwide averages he’s been researching. But what interested him more was that the number of supervisor-administrators had increased by 47 percent over 14 years.

Every year, Hutchings said, the district also reports the number of employees and their positions to the Ohio Department of Education. By the ODE’s count, there were 49 administrators in Shaker in 2015, 14 more than Shaker counted. This is because the state includes some portion of the supervisor-administrator classification in its tally. “There’s a couple of the coordinator positions that are not administrators in my definition,” Christman said. They are, however, administrators in the ODE’s eyes.

From 2007 to 2015 — the only years consistently reported — as the number of teachers declined by about 1 percent overall, the number of administrators increased by 40 percent. The ODE’s ratio of Shaker teachers to administrators went from 10:1 to 7.7:1 during that span.

The Ohio Department of Education and Shaker count administrators differently, and Shaker has seen an increase in non-teaching positions.

“I just got back from our forecast seminar,” Christman said, “and even they say you get garbage from ODE.” But even the ODE’s numbers follow a familiar pattern. The number of Shaker’s principals stayed the same. The number of assistant principals stayed the same. The number of superintendents and treasurers stayed the same. From 2007 to 2015, however, the number of administrators that the ODE recorded with the title “Supervisor/Manager” increased by nearly 50 percent. So did the number of administrative assistants. A classification called “Coordinators” went from having zero staff members to five.

This group is where the growth is found — a subsection of staff members who are administering but do not hold administrative contracts. In the words of Hutchings, administering and being an administrator are two different things. This accounts for the rise of the “supervisor-administrator.”

Morris recognized this trend. “I’ve perceived an increase of non-administrators who are in these non-teaching roles,” he said. “We’ve implemented this huge IB curriculum. We have a strategic plan that wants to see growth in math and reading. That’s where I’ve seen it increase, more so than the central administration.”

Morris attributed this partially to Shaker-born initiatives and requirements. The Innovative Center for Personalized Learning and Family Engagement. The k-12 IB Programme. The strategic plans. The data collection. “Although they relate to teaching, it’s not specifically about what we are teaching. IB is a huge commitment. It means a lot of people have to be on board,” he said.

Christman agreed that some Shaker initiatives have prompted an increase in administrators but he also sees federal and state mandates playing a large role. “Parts of all the administrators’ jobs include dealing with federal requirements,” he said. “Just from the state standpoint, not even necessarily federal programs, there’s a fair level of reporting requirements which have only grown since I’ve got into this business 25 or 27 years ago.

“From a financial perspective, we never had to do these Five Year Forecasts, which I just presented last night at the board,” he continued. “There’s all kinds of reports, audits, reviews we get subjected to from the state and the feds.

“I can really only talk to the financial side, but I know that there’s other requirements: the need for documentation for discipline, for special needs children, for gifted children, for economically disadvantaged children,” he said. “There’s just a myriad of tasks to be performed or monitored that typically come with any state or federal money.”

Social studies teacher Amy Wadsworth recognizes the increase in administrative tasks. “I would never want to be an administrator,” Wadsworth said. “They are drowning in paperwork.”

“As the number of regulations increase, the number of supervisor-administrators must increase to keep up with that workload,” Christman said. Just increasing the number of central administrators — the directors and principals — wouldn’t help fulfill these requirements.

Scafidi cites these regulations as playing a large role in staff surges as well. “[Government officials] are just laying it on at all levels. When you think about it that way, it seems almost inevitable. Blaming the principals or even superintendents is not realistic,” he explained. “It can’t be just people at a local level, because we’re seeing the rate of non-teaching staff rise across the country.”

Scafidi doesn’t think this trade-off — more administrating, less teaching — is worth it. “More and more money has been going into education each year, but the money isn’t getting into teachers’ pockets. Instead, it’s going into more support staff,” he said.

In his report, Back to the Staffing Surge, Scafidi put numbers to this assertion. He wrote that if growth in non-teaching staff increased at the same rate as student populations from 1992 to 2015, roughly $805 billion could have been saved nationally.

What worries Scafidi more is how this surge works its way into the classroom. Employing more teachers in non-teaching roles can mean less money available to hire classroom teachers, which can lead to increased class sizes and less preparation time for teachers. At the same time, district, state and national mandates require more teacher attention.

“You always hear teachers complaining about paperwork,” he said. “Any time they spend filling out a paper is time they can’t be grading. In an ideal English class, your teachers are correcting your essays and giving them back and then grading them again and again until you can do it on your own. How often does that happen anymore? The paperwork takes away from us making students better writers.”

“Think about how many tests use multiple choice,” he continued. “That can’t be the best way to test your knowledge. But teachers just don’t have time to grade anything else.”

Schmidt recognized this change. “I feel as though there have been more requests put on our time outside of the normal scope of our regular instructional duties,” he wrote.

“Most of them seem minor, like tracking conference attendees or submitting examples of formative assessments for a Strategic Plan initiative, but in addition to the increase in those teaching responsibilities, it can feel as though there are significant increases overall,” he continued.

Social studies teacher Paul Kelly expressed a similar sentiment. “I think the challenge is that time keeps getting chiseled away… as a teacher, you have to meet state requirements and IB requirements, and it’s tough,” he said.

Wadsworth said her non-teaching duties have “absolutely” grown.

Andrew Glasier, a social studies teacher at the high school, has kept track of the new responsibilities teachers have been given over the past five years. His list includes paperwork for IB, Level Literacy Instruction, Peer Assisted Learning Strategies, daily detailed lesson plans and more. In the past five years, he observed the creation of 47 new tasks taking instructional time away from teachers.

“The list grows every year,” English teacher Jody Podl said. “And the hours of the day don’t change.”

“Anything that takes away time that you could be spending with students is not necessarily a good thing,” she continued. “That’s what we are supposed to be doing here.”

A version of this article appears in print on pages 24-29 of Volume 88, Issue 1, published Oct. 27, 2017.