Counting Down

Declining birth rates mean fewer students, and funding and staffing may decline, too

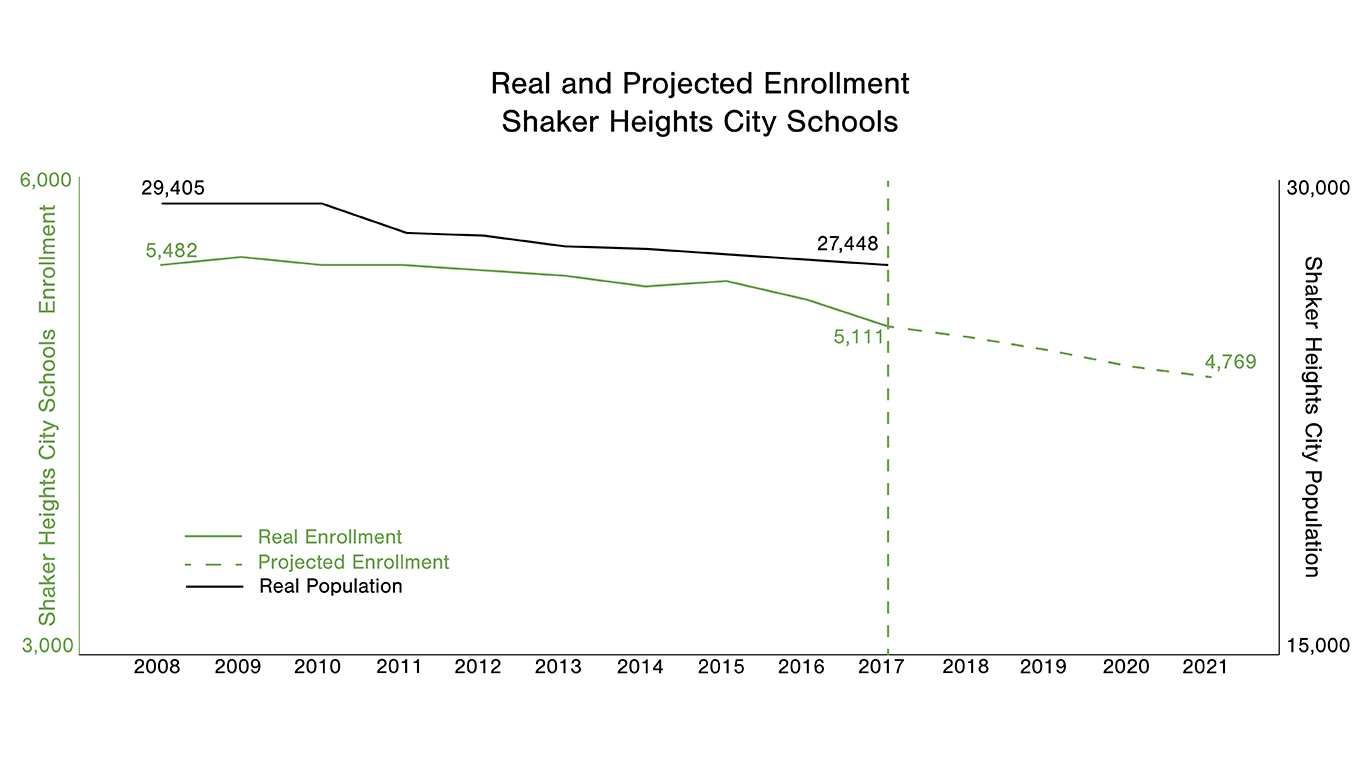

Shaker is losing students.

Over the past decade, district enrollment has declined by more than 370 students.

That’s nearly the equivalent of this year’s seventh grade class. And District Treasurer Bryan Christman expects the district to lose another 342 students in the next four years.

To anticipate and react to enrollment changes, the district contracts with Public Finance Resources, a firm that, according to their website, “was created to serve local government organizations such as school districts, townships, villages, cities, and counties with their financial forecasting needs.”

It’s their forecast that Christman uses to predict future enrollment. “They actually access live birth data, and then they project out for the five years to predict how many students might be enrolled in kindergarten five years from when they’re born,” he said.

In past years, the number of students entering kindergarten has been around 93 percent of the recorded births five years prior. Mike Sobul is Shaker’s specific consultant from PFR and helped make this forecast. Using this norm and current birth data, his firm projected kindergarten class enrollment to be around 330 students each year in the next four years.

According to district enrollment counts, senior class sizes will be close to 390 students each year in that same interval.

For the next four years, if 390 students graduate and only 330 enter kindergarten annually, the district will lose 60 students each year. Declining kindergarten enrollment thus accounts for about 70 percent of the anticipated enrollment losses. But that still leaves 100 of the 342 students unaccounted for.

Those 100 students are lost due to mobility — what Sobul calls a survival rate. “Families move out. Families move in,” he said. “On average, over the last period of years, the families moving out have net losses of 15 to 30 kids relative to families moving in.” That means at least 15 more kids are moving out than moving in each year.

In the past, mobility has not substantially affected K-7 enrollment. For example, using past averages, this year’s kindergarten class is predicted to increase by two students by the time students reach fourth grade.

In the past, mobility has not substantially affected K-7 enrollment. For example, using past averages, this year’s kindergarten class is predicted to increase by two students by the time students reach fourth grade.

This year’s third grade class is predicted to increase by nine students by seventh grade. But every seventh grade class over the next four years is expected to increase by 10 students on their way to eighth grade.

The jump to ninth grade is even more dramatic: On average, these classes will see 45 new students enter between these years. So far, these numbers suggest a net increase of students moving in.

Christman explained this growth. “Some kids will be in ninth grade but, they’re really sophomores, or they’re in their tenth year because they don’t get enough credits to be classified as a tenth grader,” he said. “Some kids go to private school for their early ages and then go to high school at publics.”As these classes advance through high school, however, these gains are eliminated.

From ninth to tenth grade, PFR predicts an average of 40 students leaving the district each year. Twenty-seven leave before junior year. Then, 20 going into senior year.

Overall, PFR predicts 22 students leaving each year due to mobility. Over four years, this adds up.

Sobul summed up the losses: “You have a little bit more move-outs than move-ins. Plus you have kindergarten classes that are quite a bit smaller.”

The next question is, why? Why is enrollment dropping?

The answer is complicated.

“It can be lower birth rates. If you have an aging population, which a lot of places like Shaker do, where the average age of the population is getting older, then obviously there’s less opportunity for young kids,” he continued. “That’s a pretty standard thing that we see in a lot of areas in Ohio, especially northeast Ohio where the population is aging.”

Christman agreed. “If the population’s aging, they become empty nesters; they’re not having kids in the school,” he said.

Shaker is getting older. Since 2009, the average age of people living in the district has increased from 39.4 years old to 40.5.

At the same time, this trend is being seen nationwide. The average age of people across the country increased by 1.2 years in the same time.

And in neighboring districts, it is even more distinct. Solon City saw an increase of 2.5 years to an average age of 44 years. The Beachwood average has settled at 50.3 years old.

And, though the number of children being born in Shaker Heights is decreasing, the amount of women who live in Shaker Heights and had children increased from 4.13 percent to 5.09 percent over those eight years.

Overall, PFR predicts 22 students leaving each year due to mobility. Over four years, this adds up.

Shaker’s decreasing birth rate may be a function of fewer Shaker residents choosing to have children. But it also could be the result of fewer women — and people — choosing to live in Shaker overall.

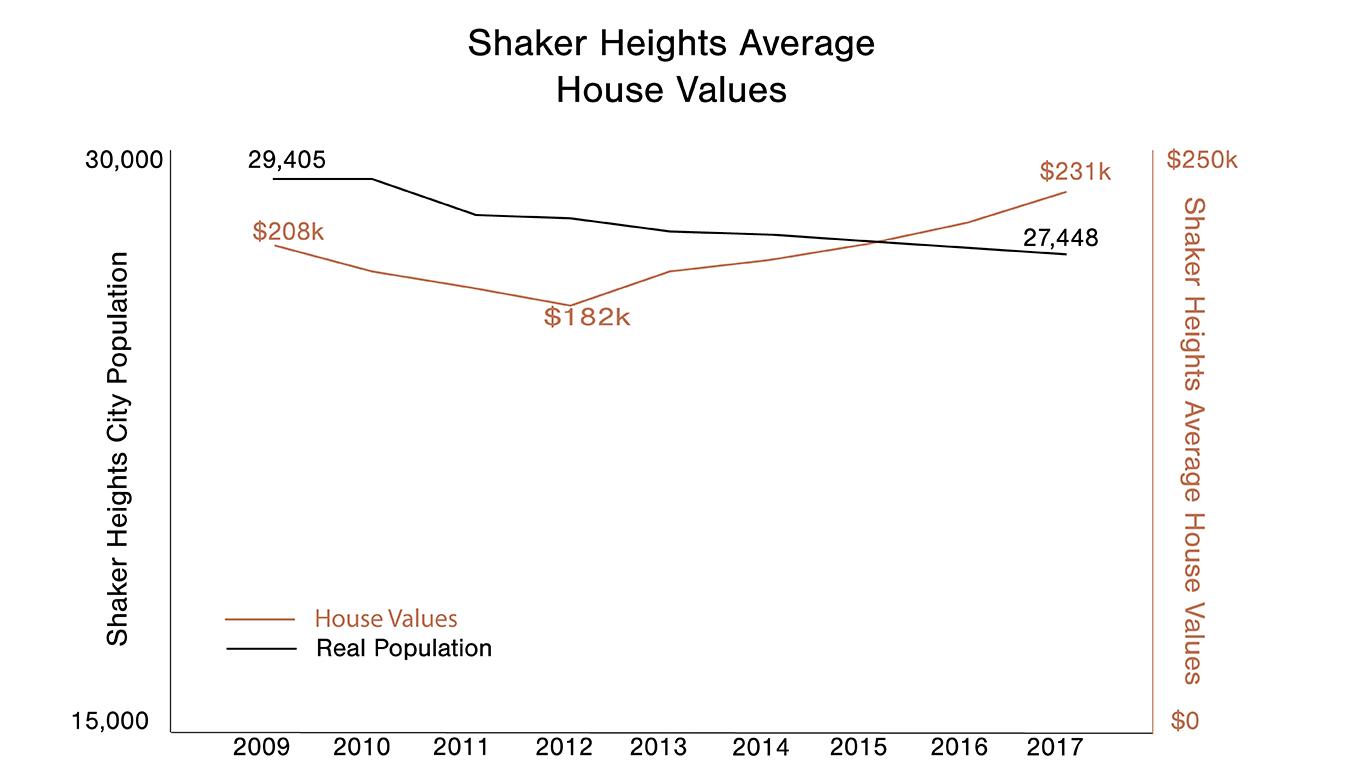

Since 2008, nearly 2,000 people have left Shaker. That’s a 6.7 percent drop in population. This mirrors, almost exactly, the 6.8 percent drop in students enrolled in the district over that time.

“A lot of it is the robustness of the economy,” said Sobul.

“In northeast Ohio, the economy is less robust than where I am here in central Ohio, where we have a lot more younger families moving into the area, which allow for more of that type of growth,” he continued. “You also have home values in Shaker that are pretty high, and so that makes it harder for younger families to be able to afford to move in.”

According to Zillow.com, an online real estate database, Shaker home values are at a 10-year high with median house selling prices at $228,100 — a figure 71 percent greater than home values on average across Ohio.

Zillow.com ranks the Shaker market as a buyer’s market — based on “sale-to-list price ratio, the prevalence of price cuts on home listings, and time-on-market” — but it’s those increasingly high house values that Sobul thinks keeps young families away.

Shaker’s population, however, has been steadily decreasing since before 1990 through periods of high and low house values.

Though they may have had an impact, they aren’t the only reason for a declining population. People aren’t just leaving Shaker because taxes are too high and houses cost too much.

The question of why enrollment is declining is answered as lower birth rates, smaller kindergarten classes and more families moving out of Shaker than moving in. But we don’t know why those things are happening.

Why are families moving out of Shaker? Why aren’t young people moving in?

The uncertainty stops here, however.

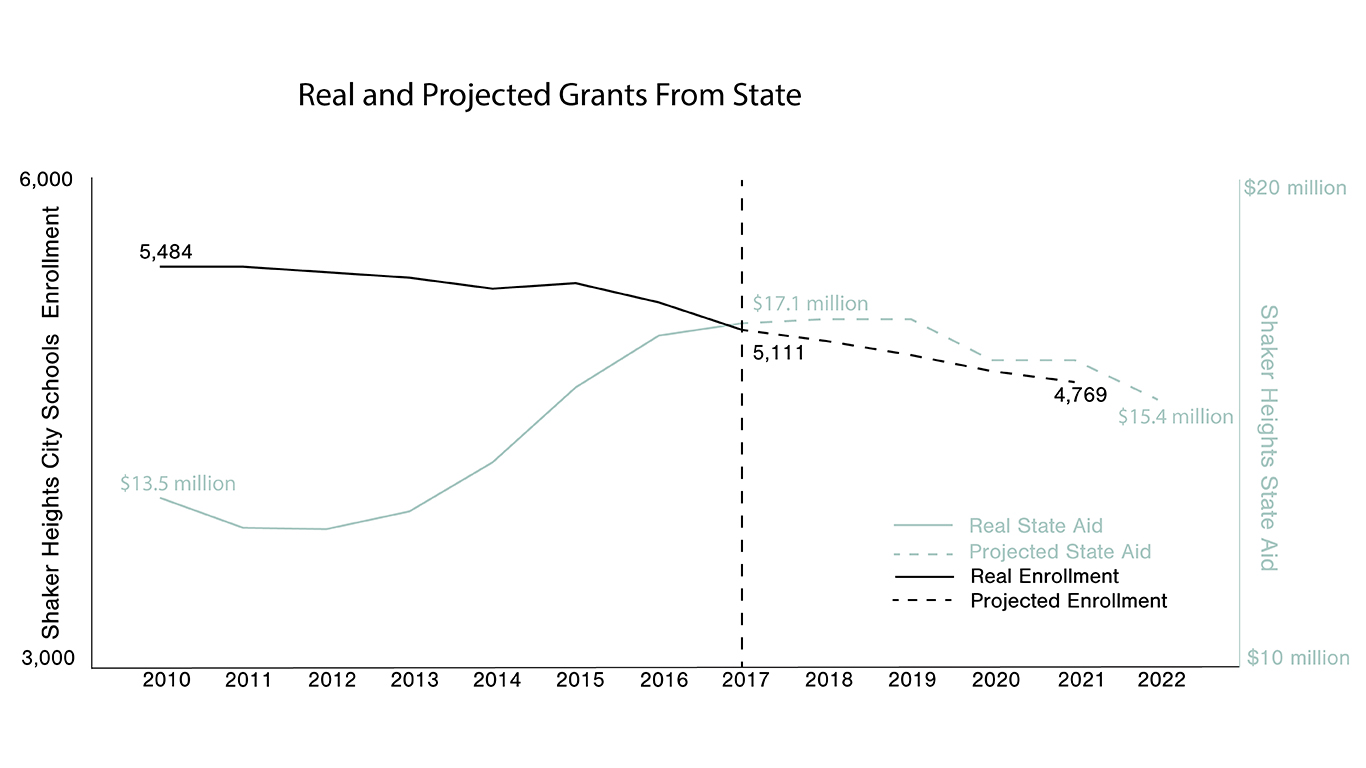

PFR and Christman are pretty sure of what’s going to happen if enrollment keeps declining. They’ve even agreed on a number: $3,379,764 lost over the next five years.

Each year, the state gives aid to districts based on their enrollment. This year Ohio gave Shaker $17 million. The majority of the district’s revenue comes from local property taxes, but that state aid still made up 18.4 percent of the district budget.

As enrollment drops, so should that $17 million. There is, however, another factor: the guarantee. Traditionally, the money the district receives is based on a formula — again, calculated using enrollment.

But if a district starts losing students, the state doesn’t want them to lose money immediately.

A guarantee basically ensures that a district gets the same amount of money from the state as the previous year. With such a guarantee, the district should not lose state funds, right?

Not quite.

Every two years, the state legislature passes a new budget, and this year, they added a requisite: If a school district loses more than 5 percent of its students over the two-year period, the guarantee no longer applies to them. Instead, the state funds they receive will once again be determined by the formula.

Despite declining enrollment, Shaker hasn’t lost 5 percent of its students in a two-year period. In the next two years, the district is expected to lose 3.2 percent of them.

In the two years after that, 3.8 percent. Without the guarantee, the district would already be receiving less state funding.

“Essentially what that is saying is that if the formula was just allowed to work with no guarantee, Shaker would actually get $954,000 less than the $17.2 million,” Sobul explained. “So, [the district] might get $16.3 million.”

Presumably, all Shaker has to do is keep their enrollment declining by less than 5 percent and they’ll stay on the guarantee and continue to receive the $17.2 million a year from the state. However, according to Sobul, no one likes being on the guarantee, and there’s a good reason why.

“There’s a potential that the legislature could come in and say, ‘This year we’re only guaranteeing that you get 95 percent of what you got last year,’ ” Sobul said.

“Maybe they’ll change it to a 5 percent drop over four years instead of two,” Christman said. “Maybe they’ll lower the percentage to four or three.”

The state rewrites the budget every two years, and in a political climate that does not make funding schools a top priority, Christman says, that danger is very real. It’s real enough for him to assume that, even if we don’t drop 5 percent in enrollment, there are still going to be budget cuts.

Budget cuts of more than $3 million. Shaker would need to add around 310 students in one year and keep those numbers up in sequential years in order to get off the guarantee.

“You’re going to be hard pressed to see 300 new students coming into the district,” Sobul said. “Whether its a 600-kid kindergarten class, or, instead of losing 25 now you’re talking about gaining 200 or something more move-ins.”

“Something like that’s going to have to happen,which, in a community like Shaker, is probably pretty unlikely,” he continued. “What that means is that as long as the current funding formula stays in place, Shaker’s most likely going to stay on the guarantee.”

“As numbers of students decline, we need to adjust our staffing levels accordingly,” Christman said. “I think the superintendent has been mentioning that pretty frequently in the last couple months.”

These adjustments can be implemented in two ways: attrition, when teachers retire or resign and aren’t replaced, and reduction. In force, when teachers are fired and aren’t replaced.

In an April 10 Board of Education meeting this year, members laid out four different options: first, no change — the district continues to replace teachers as they leave; second, attrition starting in the 2018-2019 school year; third, attrition in 2018-2019 and RIF after that; last, both attrition and RIF starting in 2018-2019.

The board laid out in more detail who would be affected by attrition and RIF.

Through attrition, the district expects about six teachers to leave (one English teacher, one math teacher, one world language teacher, one social studies teacher and several others).

Utilizing RIF, they’d expect to eliminate 14 more teachers (six from elementary schools, four from the middle school, three from the high school and one support teacher).

According to Christman, however, cutting those positions won’t be enough to make up for the loss of state funds. He expects new school levies as state funding decreases.

“Right now we’re projecting to have a new levy in 2020 that first starts collecting in 2021,” he said. The expected levy would bring in a projected $2.9 million the first year and $5.8 million every year after that.

Christman posed the question, “Do increased taxes discourage families from relocating in the district?”

If they do, higher levies would mean even lower enrollment, which would introduce the need for more levies and so on. “Obviously that’s the delicate balancing act,” he said.

There are two beliefs: either our enrollment is spiraling or it’s seasonal.

As the district introduces tactics to accommodate enrollment decline such as higher levies and more teacher cuts, either enrollment will decrease even more so, or the city will rebound to former heights.

Christman is of the latter camp. “Certainly neighborhoods rejuvenate. They turn over from being empty nesters to being families with young kids. It’s cyclical,” he said.

A version of this article appears in print on page 28-35 of Volume 88, Issue III, published May 18, 2018.