Black Is Beautiful, By Any Standard

For the first time, black women hold five major beauty crowns, but students and staff say media images perpetuate western beauty standards

Junior Tanaziona Lucious

Editor’s Note: This is the first of 15 stories reported, written, edited and revised for Volume 90, Issue II, our second print edition of the school year. When schools closed March 13 due to COVID-19, Issue II’s 80 pages were nearly ready to go to press. Initially, we chose to delay printing until in-person school resumed; otherwise, we would struggle to distribute the 2,500-copy press run. However, events throughout the country have increased the relevance of these stories, most of which were inspired by last year’s coverage of the November community meeting. We believe they are important and can contribute to local and national conversations about racism, so we will publish them online, beginning today and continuing through June. We will print and distribute them as Issue II when circumstances allow.

When junior Tanaziona Lucious decides she wants to straighten her hair, she prepares to embark on a four-hour, painstakingly frustrating process.

Before doing anything else, she checks the outside temperature and humidity to make sure her hair won’t frizz up as soon as she steps outside and won’t get wet if it rains. Lucious also makes sure she’s not playing a sport for the next three days, because sweat will ruin what she is about to do. If any of those conditions are not suitable, she leaves her hair as is.

She usually wears braids, so first she needs to take them out. She slowly uncoils each twist and turn in her hair. That step takes about 90 minutes.

She steps into the shower and lets the water seep into her thick hair for about 10 minutes. Once all of her hair is wet, she shampoos it for about five minutes, then rinses it. Next, while deep conditioning her hair, she combs away any dead strands, which catch in the wide-tooth comb. She then rinses her hair once more. She repeats this rinse, shampoo, rinse, condition, comb, rinse cycle a second time; the process takes about half an hour.

After she gets out of the shower, Lucious lathers her hair with a deep treatment oil to ensure her scalp is hydrated. If she doesn’t, her scalp will become dry, itchy and produce lots of dandruff. She covers her hair with a shower cap so the heat doesn’t escape, and she leaves the oil treatment in for about 20 minutes before removing the cap, jumping back in the shower and rinsing out the oil.

After the second shower, she towel-dries her hair, then starts the blow drying process. It takes Lucious about an hour to thoroughly dry all of her hair.

She then pulls her hair into a ponytail bun at the top of her head. And, two and a half hours after she began this odyssey, the straightening begins.

Little by little, beginning with the line of hair that grows at the base of her neck, moving right to left, Lucious squeezes segments of her hair between the flat iron’s two plates. She holds the flat iron there for two seconds and then moves on to the next section because if she holds it for too long, her hair will burn. If the flat iron accidentally touches her skin, she will jump because of the heat. Next, her rattail comb helps her divide her hair into another section. She feeds more hair into the straightening iron. Even with her careful effort to not damage her hair, she is repulsed by the odor when the iron singes some strands.

Two hours later, her naturally curly hair is as straight as a white girl’s.

After she irons her hair, Lucious must wrap it up. She grabs her comb and brush and brushes her hair so that it’s swaddled around her head. She wraps a scarf around it so that it stays compressed. If she ties the scarf too tightly, her hair will mold more than it should and lean to one side. The scarf’s pressure will create a dent on her forehead, which will start to hurt.

If she ties it too loosely, her hair will not be straight anymore or controlled when she wakes. After the unbraiding, the two showers, the four chemicals, the towel drying, the blow drying and the ironing — if she sleeps wrong and her wrap comes off — Lucious’s hair will revert to its curly essence.

With the scarf wrapped carefully around her head, she sleeps on one side of her body and is very conscious not to fall off the bed so the wrap doesn’t come off.

If Lucious is lucky, and it’s cloudy outside, with gentle breezes and little sun, her hair will remain straight for three days.

Because Lucious used to endure this process once every four months, she became emotionally and physically drained. She straightened her hair that frequently to prepare for important events or for school pictures. So she stopped using the flat iron and began using a chemical relaxer that permanently straightens hair but, because of the chemical reaction, creates heat that damages it as well. Her hair was not healthy; it was dead and no longer naturally curly and growing.

But Lucious has not straightened her hair in more than a year since she found out it was suffering from heat damage. She cut her hair and has since restored the health of her curls and is loving them.

“Beauty is acceptance of who you are,” she said. “Try to prosper on that instead of trying to conform to another standard, instead of embracing the one that you have yourself.”

Whether done with a hot iron or with a chemical, Lucious’ straightening odyssey, which transformed tight curls to smooth locks, is the result of a chemical reaction. Licensed cosmetologist Ashley Lokash, guest service leader at The Paul Mitchell School in Cleveland, explained the science behind straightening hair.

She said hair has three different kinds of bonds: hydrogen, disulphide and salt. These bonds link chains of the hair’s amino acids together.

Salt bonds are broken by pH changes in the hair. Using pH-balanced shampoos and conditioners will reform and stabilize these bonds.

Hair’s hydrogen bonds are broken when it is strained by extreme heat. Flat-ironing hair breaks hydrogen bonds to make hair straight. Hair can revert to its natural state through conditioning and careful treatment.

There are two disulphide bonds in hair. When someone chemically straightens their hair, they lose one of their disulphide bonds, which weakens the hair. “Once you lose your disulphide bond, it never comes back. You can never replace it,” Lokash said. Disulphide bonds are intact in new hair.

You might be wondering at this point, why would anyone do that to their hair?

Lucious’s mom, Lois Robinson, likes the look of straight hair. “I don’t have a particular reason why. I just like the way it looks,” she said.

We all do.

Because long, straight hair — often blond — is a foundation of western standards of beauty for women, and whether we have it or not, we learn to value it above all other kinds of hair.

Senior Madison Owens last straightened her hair six months ago. She usually straightens it once or twice a year. She said that when she does so, people often compliment her on it, and one of her teachers even told her that she should wear it like that more often.

“I was getting compliments, I felt like, just because it was so different than my natural hair,” said Owens. “It did not offend me when they complimented my straight hair, but I still don’t understand why they preferred my straight hair rather than my faux locs.”

“I know it wasn’t coming from a malicious place, but it’s definitely something that I noticed,” she said.

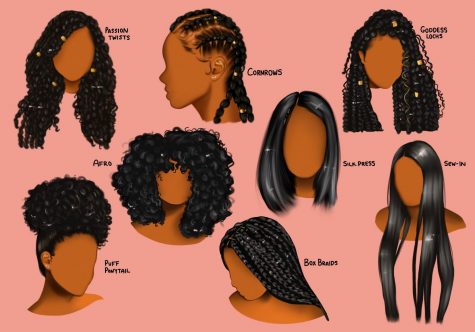

Faux locs, a temporary style, are hair extensions installed by twisting or braiding natural hair and attaching it to long, sometimes colorful, braids.

Junior Maiya Simmons said she no longer conforms to others’ beauty standards. It has been more than a year since she last straightened her hair, but she used to do it every month. “Honestly, the most times when I used to get complimented about my hair was when my hair was straight, and I haven’t straightened my hair in, like, a year, because I hated it,” she said.

Owens said that the people around her have always told her that to be beautiful, she needs to follow these and other western beauty standards. For instance, she said that during summer, when her skin tone is darker, relatives will tell her to get out of the sun because she is getting too dark.

Dr. Linda Heywood is a professor of African American studies and history at Boston University. She has written and co-written five books about the African experience.

Heywood said that it is essential for parents to teach young black girls to be proud of who they are and to assert themselves so that they will not feel confined by America’s beauty standards. “One’s personality should be formed at a very young age so that it doesn’t matter what people say about you, but you know who you are, you know what you are, you have your own standards of beauty. And you shouldn’t feel ashamed of who you are and what you look like,” she said.

Junior Wynter Brooks said that magazines shaped her sense of ideal of beauty to include white, skinny, perfect women. “I was so unsure of myself, and I feel like society molded me into the person I am today, and that’s not really a good thing,” she said. “I feel like I’ve been told so much stuff in my life about what I should be, and who I should dress like, and what I should act like that I started acting and dressing like that.” Brooks has straightened her hair only once, and that was about four years ago.

Simmons said that magazines have taught her that beauty is clear skin, long hair or perfect curls. She doubted her beauty growing up, but has stopped caring what other people think of her appearance and started to value herself. “I am who I am. I love who I am,” she said.

The effort to make hair conform to beauty standards is also expensive. According to The Los Angeles Times, black American consumers spent an estimated $2.56 billion on hair care products in 2016. Senior Mikayla Wilson said these products are costly. “It’s annoying. Not everyone has 50 to 100 dollars to spend on hair products a month,” she said.

For instance, Aveda’s Be Curly Shampoo is $21 for an 8 ounce bottle, and an eight-ounce bottle of Carol’s Daughter leave-in moisture is $12. Because black students face texturism, they are encouraged to use more of those products. Texturism is the idea that some hair textures are more beautiful than others. In particular, the looser the curl, the smarter, more attractive and feminine a black woman is considered to be.

Discrimination based on black hair can be traced to slavery, when slave owners gave preferential treatment to those who had “good hair” — a term still used today to describe black hair that more closely resembles European hair textures. Black people long ago developed techniques to straighten their hair in order to achieve a higher social status.

Heywood, of BU, said that black women are scrutinized in job interviews and in public based solely on how their hair appears. “Your hair reveals something about you that people may interpret based on their own biased notions of what hair should look like,” she said. “If I press my hair, it doesn’t mean that I want to be white. If I straighten my hair, it doesn’t mean that I want to be white. I should have choices in how I want to present myself.”

Science teacher Sharita Hill said that her 9-year-old daughter came home from school one day when she was 5 and said she wanted straight, blond hair. “After that,” said Hill, “I made it my mission to make sure she understood that different didn’t mean bad, especially when it came to her hair.”

Hill said she allowed her hair to grow and wore it naturally after her daughter was born to show her that natural hair is beautiful. She buys books and dolls for her daughter that feature black girls who have Afros and curly hair. “I try to — I guess, in a sense — flood my daughter with positive images of self so that she could understand, ‘Oh, it is different, but here’s why it’s great,’” she said.

Hill said that by wearing her hair naturally, she hopes to gain greater acceptance from her peers. “I hope that when I wear my natural hair, people view me as being more beautiful, because that is who I am at my purest or rawest form,” she said. Hill last straightened her hair four months ago and usually does so twice a year.

The decisions Lucious, Owens, Hill and Simmons make about their hair are contemporary examples of the revolutionary role hairstyles have played in black history, race and identity. The civil rights movement of the 1960s challenged both U.S. laws and social norms, including hairstyles. By reclaiming their natural hair, black activists made political statements. Angela Davis, a prominent member of the Black Panther movement and human rights activist, sported a famous Afro. That style became a symbol of cultural independence for black people.

Simmons said that the natural hair movement began with the actions of a few women who resisted and wore their hair naturally. “We need to embrace our natural hair, natural makeup without lightening our skin tone with makeup,” she said. Without the brave women wearing their natural hair, “there would still be too many young black girls thinking [they] have to straighten their hair to be beautiful.”

Hill said she notices more black students pushing back against dominant beauty standards. “In my generation, we kind of tried to submit to this generalized idea of what beautiful meant. You needed your hair straight, you needed to wear these pants, you needed to wear these shoes,” she said. “[Today], the natural hair movement is a really big thing. Students wear whatever they want. Brands don’t really mean nearly as much as they did in my generation.”

Brooks said that black people are increasingly documenting their natural beauty on social media. “Black people take pride in their hair, because our hair is just now being accepted, so we just want to show it off,” she said.

Hashtags that celebrate the power and intellectual prowess of black women include #blackbeauty and #BlackGirlMagic. More than 19.1 million Instagram posts use #BlackGirlMagic.

Simmons made the switch to wearing her hair naturally and had difficulty adjusting. “Even trying to become natural, it’s a journey, it’s a process, and it teaches you how to love yourself. It’s a struggle, honestly,” she said. “I used to think that I loved my hair straight when I was younger, but that’s just because it was socially acceptable.”

Black hair is compelling enough to inspire filmmakers. In 2009, Chris Rock produced and narrated a documentary titled “Good Hair” that examined the history of black hair throughout modern black culture. A short feature titled “Hair Love” won the 2020 Academy Award for best animated short film. The film promotes self-love by depicting a father eventually learning how to style his young daughter’s hair.

While these films make strides in promoting self-love, they do not make a difference in the policies surrounding natural hair in the workplace. In 2019, Dove carried out a research study to identify the magnitude of racial discrimination black women experience at work. Eighty percent of black women respondents said they have to change their hair from its natural state to fit in at the office. The study concluded that black women’s hair is 3.4 times more likely to be perceived as unprofessional.

Later that year, California state legislators introduced the CROWN Act. It aims to ensure protection against discrimination based on hair texture. CROWN stands for “Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair.” California was the first state to sign the bill into law. Since then, five other states have enacted the Crown Act; Ohio is not one of them.

There would be no need for the CROWN Act if western beauty standards did not prevail. These western standards don’t stop at hair; they privilege light skin over dark skin, too. While black students may be able to straighten their hair to conform to social norms, they cannot alter their skin.

Colorism is discrimination against individuals of a darker skin tone, typically among people of the same racial group. Black students and staff said that they did not think they were accepted or beautiful as a child because they did not see their skin color in the wider culture.

Brooks said that when black women are portrayed in the media, they usually have a lighter skin tone and light brown eyes. “I feel like that’s a problem,” she said.

Owens said that slavery accounts for colorism within the black community. She said that lighter-skinned slaves were granted more privileges than others. “[Slavery] started this whole divide, and we’re continuing that, we’re furthering that, and it’s just separating our own community when we should be for each other,” she said.

Jessica O’Brien, who teaches African American history at the high school through a Kenyon College course, said lighter-skinned slaves fulfilled household roles. “Somebody that looked more closely related to European was much more accepted inside the home than somebody who was much darker skinned. They would usually be out working,” she said.

O’Brien said white families would say, “You may cook my food if you’re darker skinned, but you can’t hand it to me. I want the lighter skinned person to actually be the person that’s seen.” The favoritism created animosity within black communities.

O’Brien said some slaves attempted to pass as white to escape slavery. “Many lighter skinned African Americans struggled because they weren’t always accepted by African Americans because they weren’t dark enough, and if they chose to become white, they had to go. They really had to give up a piece of themselves,” she said. “You have to give up everything of yourself that you used to know.”

The obvious benefits of passing white in American history were to live a life of social and economic privileges. Black people appearing white could escape the threat of racial violence, political disenfranchisement and powerlessness. Such benefits persist today. But one of the penalties of passing white is rejection from the black community.

Lucious gave an example. “If you’re mixed and you look more white than you do black, they say you’re not really fully black,” she said.

Junior Indira Rice said she experiences this treatment. “People don’t believe me when I say I’m black because I don’t look black,” she said. “My name is a big part of it, too, because I’m a black girl with an Indian name.”

While lighter-skin women may not always be viewed as black by some classmates, they are sometimes viewed as more beautiful by other peers, which further divides the black community.

Those features are so idealized that some white people aspire to them. Freshman Jakeia Banks said that it’s a trend today for white people to want to look more Afrocentric by darkening their complexions with spray tans. However, Banks said, “As soon as an actual person of brown skin color goes and celebrates their skin color, people look down on them.”

Rice said there is cultural appropriation on Instagram, such as white people wearing black hairstyles and darkening their skin tone. “Maybe people are trying to appreciate black people more, but they’re doing it in the wrong way. It’s kind of offensive,” she said.

Some white influencers and models on social media are passing as light-skin black or biracial women — also known as “blackfishing.” Swedish influencer Emma Hallberg is known to darken her skin tone to look like a person of color but says she only sees herself as white.

The belief that beauty is subjective and personally defined exists despite western standards. Nevertheless, since 1921, Americans have judged women’s appearance through annual competitions called beauty pageants.

Black women are usually not crowned, especially when wearing their natural hair. For instance, it took 63 years for a black woman to win the Miss America competition. But in December 2019, five black women won crowns in the Miss Teen USA, Miss USA, Miss America, Miss World and Miss Universe competitions, a historic first.

Owens said that natural hair is gaining acceptance. The reigning Miss USA, Miss Universe and Miss Teen USA are all black women who wear their hair naturally. “But I don’t think it’s preferred,” Owens said. “More people of color are getting more recognition and getting more visibility in the media, so that way we feel more confident in ourselves,” she said.

During her acceptance speech, 2019 Miss Universe winner Zozibini Tunzi said, “I grew up in a world where a woman who looks like me — with my kind of skin and my kind of hair — was never considered to be beautiful. I think it is time that that stops today. I want children to look at me and see my face and I want them to see their faces reflected in mine.”

Owens said it warms her heart to see black women getting the appreciation they deserve. “Had I been younger, and I had seen all five women being black women getting such high recognition, it would have definitely boosted my own self esteem because of visibility,” she said.

Simmons said that five black women winning pageants is a step in the right direction. “It shows the younger generation of girls that ‘I am pretty. I can be seen as pretty in the social world without having to change,’” she said.

What Americans considered beautiful has shifted over time. Hill said her views have changed about her beauty since childhood. “Growing up, I used to feel like the way I looked wasn’t good enough because the image that was portrayed, even for African American women, was that you needed to be fair-skinned, and you need to have straight hair,” she said.

Assistant security supervisor Nicole Wilson said that people used to see beauty as a woman with a skinny waist, blonde hair and blue eyes. “Now, you will see all types of sizes, colors. It doesn’t matter about the grade of your hair,” Wilson said. “I think there has been a major change in it.”

All students and staff interviewed gave their definition of beauty; no answers involved looks or skin color.

Although the most common definition of beauty relies on physical traits that you can see, touch or feel, students said they see beauty as confidence and acceptance.

For example, Simmons said beautiful people value their unique appearance. “Beauty is just loving who you are and accepting yourself,” she said. “I don’t want to be one of those people that fits in with everyone else. I’m OK if my style is different from my best friend’s style because that’s what sets me apart.”

BU’s Heywood said that by owning your beauty, you are setting the beauty standards and not letting them control you. “You cannot change who you are, so you just have to assert yourself and be proud of who you are and what you look like. You shouldn’t let other people define for you who you are,” she said. “You first have to be comfortable with yourself, and then you could go anywhere and project that pride.”

Simmons said that despite increasing awareness of socially constructed identities and norms, she cherishes her black identity. Simmons said that if she wanted to change her gender, she could change her gender. If she wanted to change her religion, she could change her religion. “The one thing that I will never change, even if I could change, is my race, because I love being black,” she said. “You have to embrace it. You can’t be scared.”

While loving yourself and your body and your hair may seem impossible, Lucious has found her strength. When I asked her if she thought she was beautiful, she answered matter-of-factly, “Yes!”

Comment using your Facebook, Yahoo, AOL or Hotmail account