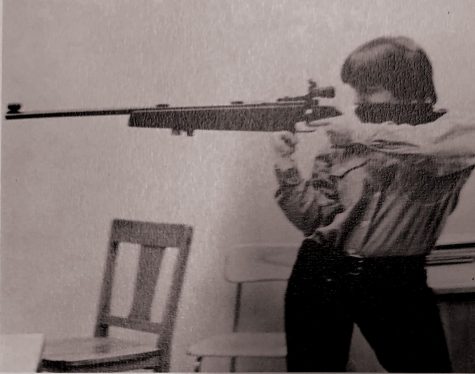

Rifle Club, 1971

Where students learned to shoot guns for sport, before students began to spray bullets to kill

Beneath the boxes and discarded trophies stashed away in the basement of the high school lie the remnants of another time.

In the basement of the high school, hidden beneath years of storage, lie the remnants of another time — one so far removed from today that it is nearly inconceivable.

They lie beyond a hallway of chain link fence that shields you from the tools and machinery stored behind it. Past it, an entrance — a heavy metal door, unlocked with a hidden key.

Upon entering, you notice only hints of what these remains once were.

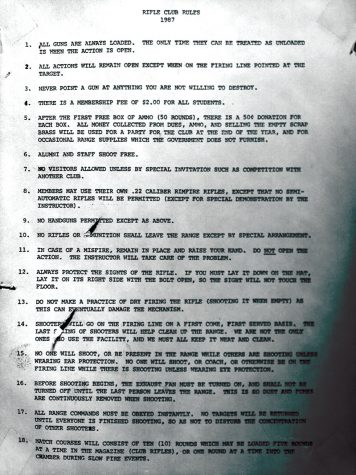

The school’s past is stored away in the corners of the room, hiding its abandoned purpose. A list of rules remains taped to a storage cabinet. One rule advises, “Never point a gun at anything you are not willing to destroy.”

Bullet holes punctuate the walls and ceiling.

The steel wall that the bullets hit is pock marked from years of use.

A faded chalkboard offers defining evidence: You are in what was once the home of Shaker’s Rifle Club.

In a time when mass shootings in American public schools are so common that they blur together, how ironic that perhaps the safest place to hide from a shooter in Shaker Heights High School is the abandoned shooting range where students fired weapons for skill and sport.

The shooting range comprised eight, 50-foot lanes leading to eight targets attached to pulley systems. Behind the targets were bags of sand, and beyond them, a steel wall. Most shooters first learned to shoot in the prone shooting position, lying chest-down on mats. Once they gained experience, students could also learn to shoot while standing or kneeling

The Rifle Club began in the 1920s, when the high school was built, and lasted until 1987. It was a place for students to find comradery, learn to shoot and compete with one another, according to physical education and health teacher John Schwartz. He remembers taking Boy Scouts to the school’s indoor shooting range before it closed.

Riflery was a club sport at Shaker, like rugby or fencing today, and members of the Rifle Club competed against such clubs at other schools. There were three categories of competition: solefire, rapidfire and timed fire. For each category, competitors had 10 shots to hit 10 small targets. The 10- to 15-person Shaker team hosted visiting schools in the basement rifle range for competition, or they carpooled to compete at another school’s range.

Students stood while shooting in the solefire event. Shooters had as much time as they needed to reload their guns after each shot, usually taking three to five minutes to shoot all 10 bullets. Rapidfire was almost always shot prone; shooters would load two five-bullet magazines into their rifles and shoot as quickly and accurately as they could. In timed fire, competitors shot in any of the three positions. They had one minute to shoot 10 bullets. According to former Rifle Club adviser Gary Johnston, the most common event was solefire.

Once everyone finished, the scores from the targets were counted. The highest score would win for each event. Sometimes, a team score was also compiled. Still hanging from the Rifle Club scoreboard is Johnston’s score sheet denoting a score of 87 out of a possible 100 points. Johnston was the last adviser of the club, which disbanded when he left to become a lieutenant in the Shaker Heights Police Department.

No one wanted to fill his place as adviser, and Shaker students were becoming disinterested in the club and range. Eventually, the school turned the range into an athletic equipment storage room. The room now houses trophies, uniforms, old health class equipment, varsity letters, bikes and crutches.

To create athletic storage, the range had to be dismantled. This process was difficult because the sand behind the targets was contaminated with lead from absorbing years of bullets. The sand had to be removed by wheelbarrow to the parking lot. Once it was removed, the Environmental Protection Agency had to oversee its disposal.

According to Schwartz, the room was deemed unfit to become a classroom because the concrete-coated floors and fluorescent lighting were not up to code. The 1,000-square-foot room’s single entrance also poses a fire hazard.

After the rifle range was dismantled, it was designated for athletic storage and is still used for that purpose today.

Johnston got involved in the Rifle Club when he started working at the high school as an off-duty police officer at the request of Assistant Principal Albert Senft in 1971. Johnston was working in the juvenile detective bureau of the Shaker Heights Police Department at the time. Off-duty police officers who work in schools are now called student resource officers. Johnston was technically the high school’s first.

Although mass shootings in schools did not occur during the 1970s, the high school was not immune to violence during the days of Rifle Club. Back then, Johnston recalled, the high school was chaotic.

During his first year in the high school, Johnston made 74 arrests for fights, assaults, trespassers, drugs, knives and handguns used by students in the school. He told stories of students from a Cleveland Heights gang called Boys About Town — BATs for short — trespassing and starting fights with Shaker students.

He relayed instances when he confiscated drugs from people. Once, he tackled a McDonald’s employee outside of the Egress — then nicknamed Hippie Hall for the number of students who went there to smoke. The employee was carrying 15 ounces of marijuana with the intention of selling it to students. He tried to run away when he saw Johnston.

Johnston recounted fights, thefts and confiscations of weapons at the high school during his time there in great detail. He remembered two students who fought with razor blades and cut each other’s faces. Once, Johnston and another officer cut a hole in the wall to spy on a locker thief. Another time, Johnston took a .38 caliber revolver from a student in the vice principal’s office.

Johnston said he would receive tips about kids who brought guns to school from other students.

After Johnston’s first year working in the high school, two more officers were added to the school patrol. This arrangement led to the current system of security guards and Student Resource Officers working at the high school today.

During his time at the high school, Johnston soon got to know the Rifle Club and took over as adviser in 1976 when the previous adviser left.

Club members paid a $2 membership fee to show their commitment to the club, according to Schwartz. Most equipment costs were financed by the National Rifle Association. The first box of ammunition that each club member used was free and consisted of 50 rounds. After that, each box cost 50 cents. The money was considered a donation to the club, since it was already paid for by the NRA. Alumni and staff, however, shot for free. The money from the membership fees, ammunition donations and sale of scrap metal was used to pay for a party at the end of the year and to buy range supplies that were not donated.

Johnston said that twice a month, adults in the community could go to the school’s rifle range to shoot in the Shaker Heights Adult Shooting Club. He said he participated in this club before he worked at the school, and that adults primarily shot handguns, specifically .22 caliber revolvers.

Johnston said some students choose to buy their own rifles, which, at the time, could cost up to $300. Students who owned their own guns would bring them to school and store them in their lockers during the day until they went to the range after school. The NRA also provided .22 caliber military surplus rifles that students in the club could use.

Students were not permitted to shoot handguns during club activities.

The rifles kept at school for club use were dismantled properly and locked away in cabinets in the rifle range when not in use.

Both Johnston and Schwartz stressed that the club was very safe and its rules well enforced. Taped to the cabinet where the guns were stored was a long list of safety precautions. Club guidelines included the proper way to store and handle guns. An adviser had to be present at the range when students were shooting, and students had to wear ear protection, eye protection and a vest when shooting.

According to Johnston, there are four fundamental rules of gun safety: Guns are always loaded and must be treated as such; never let the muzzle of the gun point to something that should not be destroyed; keep fingers away from the trigger and trigger guard; and always be sure of the target and what is behind it.

The rules of the gun club are still displayed.

The club members were a very responsible group of kids, according to Schwartz. They respected the instructors and equipment, and they followed all safety procedures. Johnston said they really wanted to be involved and be safe, and he continually encouraged safety. “Good habits are hard to break, and bad habits are hard to break,” he said, “so we always encouraged good habits.”

Sometimes, however, students would get distracted. “They knew what to do, but they’d get talking and having fun and laughing,” Johnston said. Sometimes he would have to give reminders, like keeping the muzzle of the gun pointed in the air.

Neither Johnston, nor Schwartz nor the community ever worried about dangerous incidents such as school shootings happening because of the club, its weapons or members. In fact, the club was supported by the community.

“By and large at that time, and we’re talking, you know, 40 years, 35 years ago, we had a lot of conservative people in Shaker Heights, and a lot of former military people, and they were all in favor of the Rifle Club,” Johnston said. Club members came from families with hunting or military backgrounds, and some enlisted in the military or became police officers themselves as adults.

“In World War II, the majority of the people that were drafted or joined the military had experience with firearms already, and that made it far easier for various branches of the military to train them,” Johnston said.

Schwartz said the community thought the club was great because some residents had been members. “There wasn’t the paranoia there is today,” he said.

Part of that paranoia comes from the drastic increase in school shootings within the past two decades. According to the Washington Post, more than 215,000 students in America have experienced gun violence at their school since the 1999 Columbine shooting.

Sophomore Esti Goldstein said she would be uncomfortable if a Rifle Club existed at the high school today. “I would definitely feel very unsafe, considering what’s going on with America right now,” she said. Goldstein said that the increase in school shootings and the way that guns have changed inform her feeling.

School and other mass shooters have used semi-automatic weapons including and similar to an AR-15, a lightweight military-style weapon easily modified to shoot more bullets more quickly. Citizens are able to purchase these weapons with limited background checks, and there are no restrictions for legal use. The student who killed 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida Feb. 14 used an AR-15, and that weapon has been used in 11 mass shootings since 2012, according to Stanford University and USA Today.

These mass murders have left Goldstein apprehensive, and if the Rifle Club existed today, she would not be surprised if a school shooting happened because of it. “I think under the pretense of going to gun club, people could come in and say, ‘This is my gun for gun club,’ and then we’d have a school shooting on our hands,” she said.

Johnston understands Goldstein’s views, and he said many people agree with her opinion on not using guns as part of school curriculum, especially in light of school shootings over the past two decades. “It’s, to me, a shame, but that’s unfortunately the way that society has evolved for a variety of reasons,” Johnston said.

With the increase of school shootings and change of political climate, the gun control debate has escalated. High school students, including those from Shaker, have taken action.

A Rifle Club member shoots a rifle for a Gristmill photo dated 1974.

Students participated in The March For Our Lives last spring to protest gun violence and advocate common sense gun laws. The march occurred March 24 in Washington D.C. with sister marches occurring across the country, including in Cleveland.

Shaker students also participated in a blackout and two walkouts. One was in support of the victims of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting. During the first walkout on March 14, students gathered on the turf for 17 minutes of silence, one for each victim of the shooting.

A month later, students participated in a walkout on the anniversary of the Columbine shooting, April 20, to protest the lack of gun control laws in addition to honoring victims. Students marched around the oval and participated in an open mic discussion from third to fifth period.

Johnston said something needs to be done about school shootings, but he advocates for mental health resources over banning guns.

“I would not support any ban because, out of the some 300 million AR-15 type rifles, for example, that are in the country legally and owned by various people, we are seeing less than one tenth of one percent — I don’t even know if its that big — of misuse of these weapons,” Johnston said.

He believes the issue is less about guns and more about the people using them. “I really think what we need to do is bring back the mental health network that we had up until about 1970, when the government closed all these facilities,” Johnston said.

These mental health facilities were hospitals that housed and cared for mentally ill people who were a danger to themselves or society. They were usually placed in the facilities by their families or by court order.

Johnston said when the facilities were defunded by the government, they left many people on the streets without the proper care. Johnston said this lack of support leads to violence such as mass shootings.

Johnston would also advocate for a few qualified people or police officers armed in the school to stop school shooters. The student resource officers currently in the school are not armed. He said it would also serve the purpose of building community relations between the students and the police department.

According to Johnston, in the 1970s and ’80s, the SHPD had a stronger relationship with the community and held an annual parade in which police officers marched and displayed their police cars, SWAT vehicles and gear.

The police officers who worked in the school also knew many of the students and were in touch with the community because many of them had grown up in Shaker. “It was a tighter-knit community overall back then,” Johnston said. In recent years, community relations with police across the country have become tense due to increasing evidence of police brutality, which has sparked the #BlackLivesMatter movement. The activist effort seeks justice for African-American people who have been unjustly killed by police. In 2017, 987 people of all races were fatally shot by police, according to The Washington Post. Johnston said he does not remember community tension with the police during his time in the police department.

When Johnston retired from the police department in 1992 as lieutenant, he had been head of the department’s SWAT team for the last 15 years of his career. He and his wife moved to Colorado, his home state. In retirement, he does volunteer work, drug education and writes for several magazines. Johnston is also a published author of three books. One, “The World’s Assault Rifles,” published in 2010, is 1,200 pages long and weighs nine pounds.

The 1972 Rifle Club brandishes weapons for its Gristmill photo.

Johnston said the book is used by the FBI and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives as a reference. The book is being updated and is no longer in print but is selling for more than $350 at amazon.com.

Although Johnston is busy in retirement, he looks fondly back at his time in Shaker working in the high school and with the club. “A lot of good times,” he said. “We had a lot of fun there, and a lot of good people we knew at the high school.”

Times have changed and so have the community’s views on guns. The National Rifle Association now suffers withering criticism. What was once a tool used for sport has become a killing machine people fear. Johnson is unsure what the community would think if the Rifle Club were still active -— if it would cause community backlash or change the way Shaker views guns. He said, “I’ve been away from Shaker for 26 years and a lot changes. I really don’t know.”

A version of this article appears in print on page 42-49 of Volume 89, Issue I, published Dec. 21, 2018.

Comment using your Facebook, Yahoo, AOL or Hotmail account