Colleges Should Pay Some Athletes

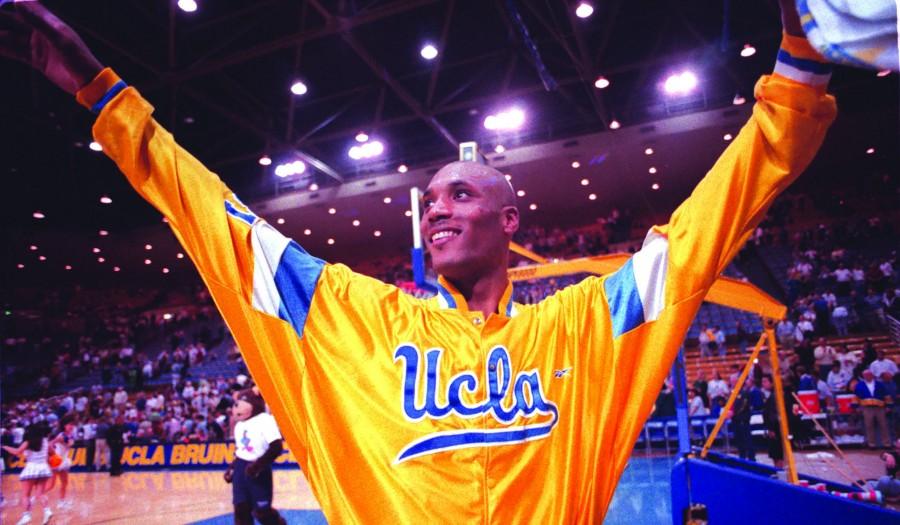

Al Seib// copyright 2013, The Los Angeles Times. Reprinted With Permission

Former UCLA basketball player Ed O’Bannon sued the NCAA on behalf of Division I football and basketball players over the NCAA profiting from merchandise featuring collegiate players without compensation.

Imagine if you spent four years of your life dedicated to maintaining a multi-billion dollar industry and you got absolutely no payment for your services. This is the epitome of how Division I athletes feel when they see their respective universities pulling in millions of dollars in revenue, while they themselves get absolutely none of it. This issue of whether or not Division I athletes deserve to be paid for their services is currently a big debate in the world of sports.

Just last year, a California court ruled in the case of O’Bannon vs. NCAA that the NCAA has violated the Sherman Antitrust Act by profiting from merchandise featuring collegiate players’ likenesses without compensating the athletes, and that the NCAA was restricting the student athletes’ right to publicity. The lawsuit focused on former UCLA basketball player Ed O’Bannon, who sued the NCAA on behalf of the NCAA’s Division I football and basketball players, and the TV broadcasts, video games and other merchandise that use Division I college football and basketball players’ likenesses.

The National Labor Relations Board made a similar decision last year, when they awarded Northwestern University football players the right to form a union and be recognized as university employees. The players signed union cards and are awaiting an appeal from the University to see whether or not they will be recognized as employees instead of just students. The NCAA has appealed both these rulings, but it is clear that major change is coming to collegiate sports. So does this mean that all college athletes should and will receive compensation in the near future?

Yes and no. Only Division I college football and basketball players should be paid, and they will be paid soon. Here’s why:

Colleges and universities make millions of dollars every year from merchandising, TV deals and licensing agreements for their football and basketball programs. According to USA Today, The Ohio State University made more than $130 million in 2014 from football alone — and they didn’t even have the highest earnings. The University of Texas made more than $165 million in 2014 from their football program. College basketball is just as profitable. According to U.S. News, CBS brought in $1 billion from broadcasting the 2014 NCAA basketball March Madness tournament. The NCAA sold CBS the right to broadcast the tournament for the next 14 years for a whopping $10.8 billion.

How much of this profit did the athletes see?

Zero.

On the other hand, smaller sports programs at Division I schools such as soccer, volleyball and lacrosse don’t make as much revenue. Although it may seem unfair to pay some student athletes and not others, these athletes from smaller programs shouldn’t be paid. From an economic standpoint, they aren’t generating any or enough revenue to have a valid claim to receive compensation. Division I football and basketball players are really the only ones generating enough value to merit compensation. One of the pros would be giving the players a fair share of revenue they helped create. The cons of paying only some athletes is that it will provoke protest from sports that produce less or no revenue.

College football and basketball programs, however, generate absurd amounts of money — none of which the players receive, except in college scholarships. For years, people have argued that college football and basketball players already have everything they need because they receive a free education. But how much do student athletes really gain from their scholarships?

According to the NCAA, only 68 percent of Division I basketball players graduate. Division I football isn’t much better, at only 71 percent. According to Business Insider, less than 1 percent of college basketball players make it to the NBA. College football doesn’t fair much better, with only about 1.6 percent of players reaching the NFL. So if only a little more than two-thirds of Division I basketball and football players graduate, and hardly any of them ever make it to the pros, are they really being fairly compensated?

Moreover, these scholarships sometimes sound better than they are. Most scholarships give student athletes free room and board, but just last year former University of Connecticut star point guard Shabazz Napier told reporters that sometimes, that wasn’t enough.

“Sometimes there’s hungry nights where I’m not able to eat,” Napier told SB Nation in April 2014. “But I still gotta play up to my capabilities.”

If one of college basketball’s premier players doesn’t have enough to eat, who knows what less prominent players at smaller Division I programs are going through?

Another argument against paying student athletes is that it will get rid of college sports’ current “amateur” label. In 2014, NCAA president Mark Emmert told CNN that he believed paying student athletes would negatively impact the tradition of college sports.

“Traditions and keeping them are very important to universities,” said Emmert. “These individuals are not professionals. They are representing their universities as part of a university community.”

“People come to watch . . . because it’s college sports, with college athletes,” Emmert said.

Emmert may be right that part of college sports’ tradition is the allure of up-and-coming stars. But does making billions of dollars off the hard work of student athletes really signify that college sports are amateur?

Furthermore, college athletes should be paid because they often don’t have time to hold jobs outside of school due to their busy schedules, unlike their non-athlete classmates. Division I colleges should at least pay their basketball and football players minimum wage for every hour they practice or play in games, in exchange for not allowing them the time to get jobs. Such a practice is completely fair from an economic standpoint, because athletes sacrifice their opportunity to work when they go to practices or games.

Senior basketball player Nathan Bouie believes that Division I basketball players should be able to have some say in their workout and practice schedule.

“I think they should have free range to accommodate their busy schedules,” said Bouie. “They should be able to skip a morning workout or miss a practice or two if they were up all night studying or have to take an important test.”

Whether the NCAA gives student athletes more control of their schedules or not, players need to be a bigger part of the overall business that is Division I basketball and football. Perhaps colleges should set up bank accounts for all Division I basketball and football players and pay them once they graduate, but only if they graduate. This way colleges and universities could use paychecks to incentivize graduation and at the same time provide compensation for athletes when they no longer fit under the “amateur” label.

No matter what the NCAA decides to do, change is necessary and looming. It is impossible for a multi-billion dollar industry to provide their most productive workers with no compensation and expect them to stay happy.