What About Mental Health?

We all must be conscience of students’ mental health

Her breath begins to quicken. Her hands are shaking, her palms sweating as she asks to use the restroom. Sprinting out of her Spanish classroom and into a bathroom stall, she lets out silent screams as tears stream down her face. It feels like her throat is closing.

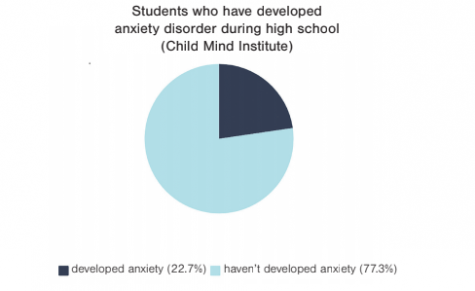

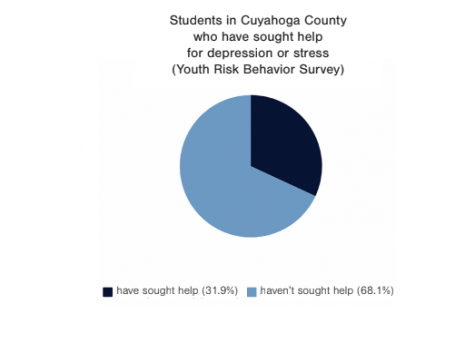

According to the Child Mind Institute, by the time teenagers graduate high school, 31.9 percent of them will have developed some sort of anxiety disorder. During the short time I have been in high school, too many of my friends have become part of this statistic.

While I haven’t developed clinical anxiety, I do experience panic attacks and high levels of anxiety. It’s a problem that affects all aspects of my life.

I am not the only person at Shaker Heights High School who has experienced some part of this disorder. So many students have endured experiences similar to or worse than mine.

In 2017, 22.7 percent of students who took Cuyahoga County’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey reported that they saw a mental health professional about stress and depression.

According to the Child Mind Institute, depression and bipolar disorder affect 14.3 percent of high school students. This statistic could include one of your friends. How many of us know a student who struggles with depression or anxiety?

How many of us know a student who regularly stays up doing homework until three in the morning because anxiety attacks make it difficult to complete assignments?

How many of us have seen a student come to school after getting two hours of sleep, clearly too tired to participate in class?

These students push themselves because of a fear too many of us share: falling behind in their classes.

The culture in our school pressures every student to succeed in the same way. Every student is expected to push themselves as hard as possible in every area of their life in order to secure a comfortable future.

One would assume that school administration would take extreme measures to protect its students. After all, the school’s number one priority, as they always say, is our safety. Though many say it isn’t the school’s responsibility to fix the problem, the school has implemented resources such as flex nights or the zen room. But it’s not enough.

What else should be done?

While administration and some parents believe mental health is a student’s responsibility, the school should not avoid the subject. Much of what causes anxiety could be changed by the school.

The national conversation about teenage mental health is beginning to expand, and it is important that Shaker follows this trend with conversations of our own.

We need a nation-wide intervention with students to explain that the amount of sleep they lose, or how mentally exhausted they are, is not a measure of success. Both are unhealthy and self-destructive ways of thinking. This conversation needs to encourage students to take care of themselves, and it needs to be led by adults. Because, for us, exhaustion is all we’ve ever known.

Priorities need to change.

We must treat mental illness as seriously as physical illness. Students should feel comfortable telling their teachers they need to leave class and visit the nurse because of something they’re struggling with mentally.

By eliminating this stigma, more students will feel free to ask for help rather than suffering in isolation.

Another necessity is changing the attitude about how students choose what classes to take.

Students are always expected to challenge themselves, which is good.

However, there is such thing as being too challenged. Most students, teachers, parents and administrators don’t address this.

Shaker schools and parents flaunt students who get into top colleges, which creates a misconception among other, younger students that they must get into these schools to be someone the district and their family are proud of.

While it can’t be expected that high school students know exactly what they want to do with their lives, most know where their general interests lie.

For example, I dropped down a math level to make room to succeed in AP U.S. History, a course that I am fascinated by.

Dropping down to Algebra 2 Honors from 10 Honors Math gave me more time to do homework for other classes because my nightly workload for math decreased significantly. The decision allows me to get more sleep, which makes me a better student and more importantly, mentally healthier.

Often, students take the highest level classes possible to please a college, but the decision to take a class should be a decision to make the student happy, not to impress a man or woman sitting in an admissions office hundreds of miles away.

When I dropped down a math level, all I heard from my friends was that I was capable of succeeding and should remain enrolled. What most of them didn’t understand was that I was protecting my mental health.

The school also needs to begin the process of eliminating the competitive culture that has existed at Shaker for too long.

Often, when tests or essays are passed back, students share their scores with peers. This practice can cause stress and even induce panic attacks when students realize they didn’t perform as well as others. It certainly has for me.

Students need to understand that while there is peer pressure to share grades, they don’t have to. And it would be healthier not to.

When students discuss scores, whether in person or over text or on social media, they are doing so to make themselves more confident or less anxious.

Students who do well on a test will share their scores to boost their self esteem through positive feedback from peers. Students who don’t earn a good grade on an assignment share scores to feel better by learning that other students did the same.

Last month, after an English test score was entered into ProgressBook, my phone blew up.

Almost all of my classmates were sharing their scores, and nearly everyone had earned a higher score than I did. It was discouraging.

It was like looking at the same bad score for the first time all over again.

I am sure I am not the only student at Shaker Heights High School who has fallen victim to this destructive habit.

Teachers must at least attempt to put a stop to the practice, and students need to understand it is not only hurtful, but it can also cause students to experience anxiety attacks or other harmful effects as well.

Tight schedules can also lead students to unhealthy outcomes. Generally, I go straight from school to practice or work and then home and immediately start my homework.

This schedule often pushes me over the edge because I often don’t get time to myself for five days straight. However, only students can fix this problem.

One of my cross-country captains reminds me to take at least 15 minutes for myself daily. Since I began doing so, I have felt happier and healthier

To battle this epidemic, mental illness must be taken seriously by students, parents and schools.

All parties must help students improve their mental health. We must lessen stigma and change our school culture. We need a viable effort from everyone.

If we don’t, the situation will only grow worse.

A version of this article appears in print on pages 34-37 of Volume 89, Issue I, published Dec. 21, 2018.

Comment using your Facebook, Yahoo, AOL or Hotmail account

Gerette | Feb 6, 2019 at 9:23 am

Until we put mental health on the same level as physical health, there will still be a stigma. I hope the teachers and staff read this and take it to heart.