Time For Change

We are all trying to be Hermione Granger, without the time turner. We take on six or seven classes, each with hours of homework and throw ourselves into crazy numbers of extracurriculars. There is just not enough time and something has got to give. Usually, this something is sleep.

High school students share three realities during the school year: overwhelming amounts of homework, time-consuming extracurriculars and, most importantly, sleep deprivation.

This issue’s prevalence has grown not only in high schools, but also in the psychiatric and journalistic fields.

The National Sleep Foundation estimated that teenagers need at least nine and half hours of sleep per night. So imagine their dismay when their 2014 survey revealed that less than half of American children get at least nine hours of sleep each night, and 58 percent of 15- to 17-year-olds typically sleep fewer than seven hours.

But we high schoolers already knew that. We live it every day.

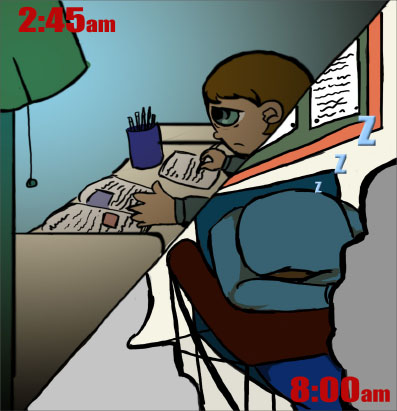

“We have so much work to do that we’re just up late,” said sophomore Mathieu Girard, who takes both Advanced Placement

Biology and Advanced Placement U.S. History. “So at the end of the day we’re just really tired, but we still have work to do, so we end up going to sleep at like two o’clock in the morning.”

From there it’s a downward spiral. Advanced Placement Psychology teacher Sylvia Sheppard thinks that students’ lack of sleep takes a toll on their learning.

“When you’re tired, your body goes into a mode where it wants to fix whatever it’s lacking. So if you’re hungry during school, you’re not actually thinking about what’s going on in the classroom, you’re thinking about your next meal. Same thing goes for sleep,” Sheppard explained.

“If you’re that tired, either you’re half-out in class, trying to get rid of that need for sleep, or you’re planning when you’re going to sleep. Can I go home? Can I take a nap? And that becomes the preoccupation, therefore, you’re not paying attention in class to what you need.”

“Students who stay up to study, that’s not beneficial either,” said Sheppard. “It’s better to get a good night’s sleep in order to perform well in school than on a test, than it is to cram until really late into the night.”

Still, many students choose to stay up for that extra hour or two at night. But going to bed late makes students tired at school, causing them to fall asleep in class.

“There are students who frequently fall asleep in class, and it’s not that they’re just being rude and putting their heads down, it’s that they can’t keep their eyes open. So yes, I do think [lack of sleep] is an issue,” said Sheppard. “I do see students compensating. A lot more students carrying around coffee.”

However, as much as lack of sleep is a teenagers’ choice of homework over sleep, their bodies also play a role. Adolescents’ body clocks are by nature wired differently than those of adults and younger children.

According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, teens will usually not feel sleepy until 10 p.m. or later, no matter how much homework they have.

By nature we are night people, but we are forced to act as morning people.

“As we mature and go into the teenage years, the natural tendency is the body’s internal clock, which is usually set for a little bit longer than a 24-hour day. So there’s a tendency to not get sleepy until later into the night and then want to sleep in later into the morning,” said Metrohealth physician Dennis Auckley, Associate Director of the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine.

“Not all kids do that, but it’s the average trend, and it becomes a problem when they have to get up early and get to school on time. They may have difficulty falling asleep at night because their brain and their body are still awake.

“Because you need to get to bed earlier, it can be very hard, because your own natural tendency is not going to allow you to do that,” said Auckley.

“The result of that is that they’re having trouble falling asleep early enough at night, and they have to get up earlier than what their internal clock wants them to. So they develop a lack of sleep, or what we call a chronic partial sleep deprivation,” said Auckley. “That can have significant effects on their mood and level of alertness, which can translate into problems with school and behavior, and also even potentially performance in school.”

At first, high schoolers’ lack of sleep affecting their learning abilities was a mounting issue. Then it became a real problem. Now it’s a genuine concern.

It all began in 1999 with Congresswoman Zoe Lofgren, who posed the “ZZZ’s to A” act. It encouraged school districts all over the country to move their start times to no earlier than 8:30 a.m.

Her hard work to pass this bill has continued through the past 15 years. She is now working with the National Sleep Foundation to supply her argument with realistic statistics about this problem.

But what would Lofgren’s bill look like in action?

A study by Dr. Kyla Wahlstrom at the University of Minnesota suggested that pushing back school start times would help students both academically and mentally. Based on her research, the Minneapolis Public School District pushed back their starting times of seven high schools from 7:15 a.m. to 8:40 a.m., and the results were very encouraging.

Dr. Wahlstrom found that students gained at least five extra hours of sleep per week, and saw an improvement in attendance and enrollment rates, increased daytime alertness and decreased student-reported depression.

However, we must also acknowledge the disadvantages of this change.

We will not pretend that instituting a later start time for the high school would be easy, but our health, in the short and long term, matters most. The well-being of the high school’s student body is at stake.

“I think the understanding of [starting school later] is sound enough that I think it makes sense, and there is some data supporting it. It’s not universal if you look at the whole body of literature, not everything is saying there’s a clear connection, but I think there’s enough information out there to suggest that it probably is important,” said Auckley.

“The flipside to that is that it really has to be a cultural change, because you have to balance making this change. What’s going to happen with extracurricular activities, sporting activities, busing and parents who have to bring their kids to school and pick them up?

“So it really has to be well thought out. I think from the standpoint of a sleep physician, it would be a good idea to make that change, but it’s a hill you’ve got to climb.”

Sheppard agrees that late start would be helpful in theory. However, she knows that teenagers are creatures of habit, and will only fall back into the same repetitive cycle.

“I don’t know if making school later is going to necessarily help students actually get more sleep. I think on Tuesdays some students sleep in, but a lot of them are already here and studying,” Sheppard explained.

“Teenagers should get somewhere between eight and 10 hours a night of sleep, and they’re probably getting around six and compensating during the day.

“The key would be that you actually do sleep eight to ten hours, and not just start school later and still deprive yourself of sleep,” said Sheppard. “You still stay up until three in the morning, whether you’re playing video games or doing homework.”

Auckley and Sheppard are both right. Not only would changing school start times require re-working the schedule, it would also cause logistical problems in the community.

All or nearly all schools in the area end their school days around three p.m. If Shaker pushed back the school day, coordinating after-school activities with other schools would be harder. Specifically, sports. As is, athletes already miss class time for games.

“Falling asleep in class becomes a big issue. I feel like it impedes learning and also development as a student,” said senior athlete Arpit Agrawal. “Especially as a student athlete, it takes a toll.”

Additionally, if the high school offered bus service for its students, we would have one less hurdle to clear. The district would not have to worry about the logistics of altering the bus system to different start times, because for the high school, there isn’t one. However, the bus schedule would have to be considered if later starts were implemented throughout the entire district.

A constant fight rages between what we have done in the past, and what we should change today.

We live in a society where our health is an increasingly popular subject. We have begun to move towards healthier foods and greater exercise, so it’s only a matter of time before we implement improvements in our sleep habits.

“[Lack of sleep] has a great impact on mental health. Again, with the way that teenagers’ brains work, the emotional part of their brain is starting to develop faster than their frontal lobe, which is their judgement. When you’re tired, you become very emotional. You will overreact to things that should be benign. You think that they’re much bigger,” Sheppard said.

“It can even get to the point that if you’re so sleep deprived you can hallucinate. It’s the type of hallucination where you’re not sure if you’re dreaming something or if it really happened,” said Sheppard. “You’re not sure what’s real or not real. It can definitely impact mental health and your perceptions and how you respond to events with your emotions.”

Along with emotions running high, those who experience what Auckley calls “a chronic partial sleep deprivation” are prone to physical health issues as well.

“[There are studies that bring] normal people in who typically sleep eight hours a night, and then restrict them and their sleep, say six or four hours a night, and then study them and see what happens to them after a week,” Auckley said.

“We start to notice some changes. The most pronounced ones being that there’s changes in certain hormones in the body that affect appetite, specifically cravings for certain types of food, particularly unhealthy food,” said Auckley. “So there’s a pretty good understanding in associating a chronic partial lack of sleep with weight gain and leading to obesity.”

“We’re seeing that starting at a younger age, and that can translate, as well as by some other pathways, into earlier onset of some adult disease, which we usually didn’t see previously in kids,” said Auckley. “Adult onset diabetes, blood pressure problems, and even sleep apnea. Obviously weight gain is a complex phenomenon, and has more to do with just sleep . . . but the lack of sleep is probably a factor that’s important in the overall equation, and can be part of the pathway leading to these other problems.”

High schools have started at the same early times for years, and older generations have yet to show signs of those start times’ “long term effects.” However, Auckley thinks it’s possible.

“Since the field’s fairly new, we haven’t had enough time to study teenagers and track forward to see what happens twenty years later. But it’s very likely that it would hold true,” Auckley said.

Whether or not that would be enough to change school start times once and for all remains unclear.

The bottom line is, teenagers’ mental, emotional and physical health are being put at risk. We’re reaching a point in history where students’ performance on tests is considered more important than their quality of life. Late starts or not, something has to change.