Texts and Context

Choosing what works to teach might be one of the hardest tasks an English teacher has to face. There are just SO MANY great texts — how do I narrow it down? And what about all those boxes I need to check in my curriculum: It needs to be challenging but accessible, engaging but intellectually rigorous; I need to include a diversity of authors by gender and ethnicity; I want students to explore a variety of genres and media.

In many ways, “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian” by Sherman Alexie was a perfect book: An author from an underrepresented minority pens an engaging bildungsroman, swinging from laugh-out-loud humor to tugging on the emotional heart strings, all while dealing with big, real-life issues. It even has pictures!

When sexual misconduct allegations against Alexie first came to light in 2018, it was right before we were about to start the book in my ninth-grade honors class, and not that many people had heard about them.

I decided to wait until students brought up the issue. We discussed it briefly toward the end of the unit and moved on. Last year, however, with the Me Too movement gaining momentum, I knew we’d have to confront the matter head-on, and so I brought up Alexie’s transgressions right at the start. I let my students know that we teachers had reservations about the book, and that I would be interested to hear their take on the issue.

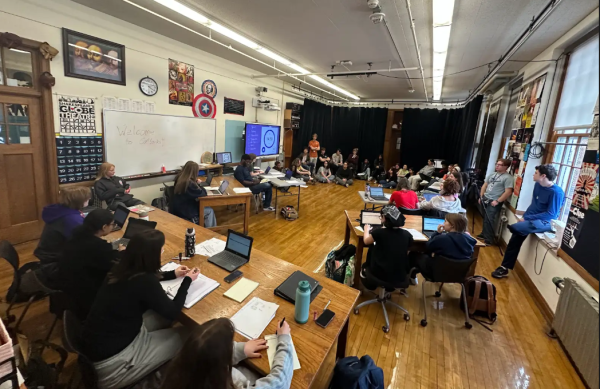

Teachers sometimes talk about the “magic lesson,” when a perfect storm of teachable moment and student engagement come together and the results exceed all expectations.

That was my experience teaching “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian” last year. Throughout the unit, I was astounded by the maturity and insight my students brought to bear on our conversations.

I found myself recounting entire seminars to colleagues in the department office. The connections and observations students made let them explore ethics and morality in ways that I don’t know would have been possible with a less controversial text.

They discussed objectification of women and toxic masculinity; they explored cultural appropriation and media representation and the importance of giving voice to marginalized people; they debated what to do when bad men make good art.

Ultimately, they were nearly as torn about the text as I was.

As satisfying as it is to condemn all offenders with a broad brush, I believe there is a spectrum to bad behavior.

There is a difference between Al Franken and Bill Cosby, between John Lasseter and Harvey Weinstein, and between Sherman Alexie and R. Kelly. Many of my students recognized this, too, and saw enough value in the text to argue for keeping it; very few felt strongly that it should be removed, but the exchange of ideas between the various camps was a learning experience that cannot be replicated artificially.

This year, my plan is to teach the book.

I don’t know if we’ll capture lightning in a bottle again, but if we can, it will be worth it.

That is not to say, however, that I’m not on the lookout for a replacement. I (along with other ninth grade teachers) read about two dozen books this summer for that purpose, and the search continues.

If we can find another “perfect book” without so much baggage, great — and I’ve read a few with promise.

No matter what we read, though, I believe my students are capable, engaged and sophisticated enough to navigate the challenges that any text — or its author’s life — offers.

A version of this article appears in print on page 59 of Volume 90, Issue I, published Dec. 9, 2019.