Paper and Pencil to Computer and Wi-Fi

As more homework must be completed online, the equity gap increases, and so does students’ stress

After becoming a Google district in 2017, Shaker teachers began using Google Classroom to assign homework to students.

Once upon a time, a boundary existed between the school building and the home. A student would sit in each class for 50 minutes a day and leave with an assignment to complete before class began the next day.

Today, instructors can turn any place with a computer and internet connection into a classroom. Suddenly, we don’t have an assignment tucked somewhere in a folder that’s due tomorrow; we have a screen staring at us as the clock ticks down the minutes until an online assignment is overdue.

Schools nationwide are turning to digital learning. However, this technology is only valuable if every student can access it. And even then, the extra stress that accompanies these assignments leaves us wondering if the effort to capitalize on technology is worth it.

In 2017, Shaker became a Google district, creating Gmail accounts for every student and encouraging teachers to employ Google Classroom — a free, cloud-based service. According to shaker.org, this decision was characterized as an enhancement of district practices “to help increase efficiency, facilitate communication and support the already great work being done by our students, faculty and staff.”

French teacher Eileen Willis began using Google Classroom in October 2016 after attending a conference organized by the Ohio Foreign Language Teachers Association. “I learned how to set up a Classroom and I went to a couple of other short, general trainings for Classroom teachers,” Willis said. “There are also several teachers in the department who have experience, and some who were really helpful any time I made an error.”

She continued, “I really have not heard many students complain about [Google Classroom]. Most people seem to view it positively.”

Margaret Bartimole (’18), however, expressed concerns about the use of Google Calendar, another cloud-based Google service, and Google Classroom. “I just think teachers should tell us our assignments in human form because it feels too electronic — not personal,” she said. “No one is explaining what we’re doing, no one’s explaining why we’re doing it. It’s just like, ‘Check Google Classroom.’ I don’t like that.”

Bartimole also said that it’s harder to stay atop online assignments. “I feel like it’s easier for me to get behind on Google Classroom. I feel like I hold myself more accountable when I turn in a physical copy,” she said.

EdWeek reported that 68 percent of districts nationwide, including our own, use Google Classroom to remind students about due dates, upload notes and assign online work.

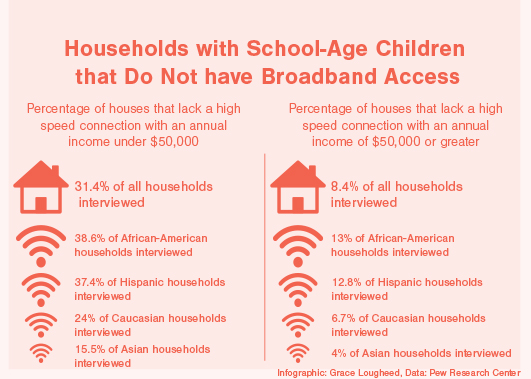

But more teachers making this switch produces a widening technology gap. According to the National Education Association, approximately 70 percent of teachers were assigning homework that required internet access in 2009. However, at that time there were 5 million American households with school-age children that did not have high-speed internet service.

Given that the NEA study was done nine years ago, it’s safe to assume that today more than 70 percent of teachers assign homework requiring internet access.

The technology gap is essentially an extension of the achievement gap. Students without internet service or personal computers risk falling behind as more assignments are accessed and completed online.

Willis expressed understanding for students without internet access at home and their rare situation in a screen-ruled world. “Everybody can always tell me that and they can either come in and work in class, or work during conferences” she said. “I always give extensions for situations like that. It’s not a problem.”

Executive Director of Communications and Public Relations Scott Stephens noted an item in the district’s Five-Year Technology Plan that states that during the 2015-16 school year, the district would “perform a survey to determine technology accessibility in homes throughout Shaker Heights.”

However, this study was never completed. According to Stephens, “It will be rolled into our new technology plan.”

Students without internet access must jump over extra hurdles to catch up, including spending extra time at before- and after-school conferences, the library and friends’ houses.

Students without internet access must jump over extra hurdles to catch up, including spending extra time at before- and after-school conferences, the library and friends’ houses.

For these students, homework can’t be done in the comfort of their own home. They must spend extra long hours — tacked on to the end of an already long school day — in conferences or at the library, propped up at a desk, staring at the harsh blue light glowing from a computer screen. And for some students, even making it to the library before it closes may be difficult. The Shaker Heights Public Library closes at 9 p.m. on weekdays and 5:30 p.m. on the weekends.

I spent half of high school exploring new tactics to catch up to my classmates because I didn’t have access to a computer at home. Teachers are usually understanding when it comes to these circumstances. However, discussions with them were only half the battle — the other half was finding a way to complete the assignments.

Homework assigned on websites other than Google Classroom was the most difficult to complete because it was harder to access. My first generation iPad wasn’t compatible with websites that required an Adobe plug-in, such as Pearson’s Mastering Biology or Mastering Chemistry.

To dodge this roadblock, I spent time in biology conferences. However, there were days when I wasn’t able to make it to conferences due to sports, clubs, my job or the demands of other classes.

When my teacher would ask everyone about an assignment that I wasn’t able to complete, I would raise my hand and, before saying a word, he’d laugh, nod his head and the class would join in. It was lighthearted fun, but it concealed a much bigger issue: In 2017, the idea of a student not being unable to complete an online assignment was comical.

Online assignments posted on Classroom are usually due at midnight, requiring students to upload and submit them by that time. If a student submits the assignment past midnight, it is automatically marked as late. However, it can still be accessed.

Not every online program allows this flexibility. On Cengage, an online program commonly used by science teachers, students cannot access their assignments after 11:55 p.m. So, for students who only have internet access at school, it’s impossible to complete these assignments for late credit the next morning.

Once the clock strikes midnight, the algorithm in the computer marks outstanding online assignments as missing, automatically reducing a student’s grade. While some teachers do offer the option of coming to conferences to reopen the assignment, it usually can only be completed for late credit. Teachers differ in their late credit policies; they can assign anywhere from full to partial to no credit, which can discourage students from completing the assignments as it may not help their grade in the long run.

Additional stress caused by online assignments is seemingly justified by the belief that they help students learn — whether skills future jobs or by keeping them organized — but without access, students cannot practice the skills the assignment is designed to reinforce.

Even for students with internet access, online assignments can be stressful. The digital classroom redefines homework, forcing students to adjust their habits. Going home is supposed to allow students time to themselves without teachers and deadlines. Any work they’re expected to do can be completed on their own terms — right when they get home, late at night, or the next morning. Because homework is assigned to help students review, as long as they complete and understand it, it has served its purpose.

However, students now have less autonomy when they complete their work as it must be done on a computer screen and turned in before they go to sleep, rather than completed the next morning or throughout the day before class. Allowing students to turn in homework when they should be sleeping encourages the belief that it’s acceptable to lose sleep over schoolwork.

Just because we can do something doesn’t mean we should. Just because we can make something digital, doesn’t mean it’s better for learning — especially if that something isn’t equally accessible to everyone.

Being relatively new to the Google game, Shaker teachers are discovering the lengths they can go to with their online assignments. But individually doing this creates inconsistencies in the demands on each student and confuses us as we try to figure out the new way to navigate homework.

Teachers, please consider some uniform approaches to limit the demands you make of us online, such as making assignments due at the beginning of class the next day and thus giving students as much time to finish online assignments as they would paper ones.

The age of digital learning has arrived and will not end. It’s crucial to discuss what can be asked of students at home, what’s fair and how the teachers and the school board are going to work to close the equity gap created by technology and online assignments.

A version of this article appears in print on page 44-45 of Volume 88, Issue III, published May 18, 2018.