The Definition Dilemma

McKeon: Defining bullying, although harder than it seems, is crucial, but so is emphasizing empathy

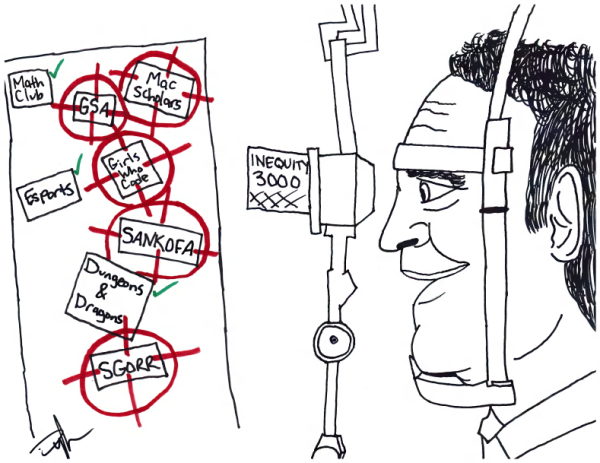

On a frigid Sunday night in January, the Student Group on Race Relations’ 19 core members are packed into their adviser’s living room.

After a break for the quintessential SGORR snack — Papa John’s pizza — the group begins its activity. Each member receives a sheet of printer paper and the following instructions: write down a time you saw bullying, were bullied or were the bully.

Five minutes pass. Then 14 members share. When sharing is done, senior Shaun Roy tells members to ball the paper up; then he says to smooth it out.

The activity is one big analogy. Roy points out that the creases are permanent, just like harm from bullying. He says they did the activity in a sixth grade classroom; every kid shared, and the day ended with the class face down, crying into their desks.

This year, there’s been a movement inside of SGORR to focus more on bullying, reflecting the national progress anti-bullying campaigns have made recently. When the core members discuss SGORR’s role in discouraging bullying, a few common themes arise: How should the group approach anti-bullying activities for the younger, more impressionable fourth graders? How can groups best communicate with teachers who have concerns about SGORR tackling the topic?

And — the most interesting question — how should the group define bullying?

It’s a question school districts and state legislatures across America are answering, and it’s more difficult than it sounds. If we define it too broadly, bullying becomes too vague to address; if we define it too narrowly, we may neglect victims of bullying who don’t fit our arbitrary definition.

In “Defining Bullying Down,” a column published by The New York Times, author Emily Bazelon wrote that the definition of bullying is “expanding, accordionlike, to encompass both appalling violence or harassment and a few mean words.”

We must be careful bullying doesn’t become a catchall for any aggressive behavior; the broader it gets, the harder it is to address. What if instead of waging a War on Terror we waged a War on a Specific Aspect of Terrorism? It’s very difficult to win a war on an amorphous noun — see also: War on Poverty, War on Drugs — and bullying is no different.

But what if we narrow the definition? What if it becomes so narrow (or perceived as so narrow) that kids don’t feel comfortable voicing their pain?

According to the district website, between Aug. 26 and Dec. 31, 2013, there were 18 “incidents of harassment, intimidation and/or bullying leading to a suspension or expulsion” at the middle school. There were three at the high school and five at Woodbury. Would there be more suspensions if the district broadened or clarified its definition of bullying? As Bazelon wrote, differentiating between bullying and what kids call “drama” is another problem entirely.

The American Psychological Association defines bullying as “a form of aggressive behavior in which someone intentionally and repeatedly causes another person injury or discomfort.”

The district uses a similar definition, provided by the state. The APA’s definition is helpful because it provides a three-part test: aggressive, intentional and repeated. Teachers and administrators should clarify this definition so that students may know where bullying begins and ends.

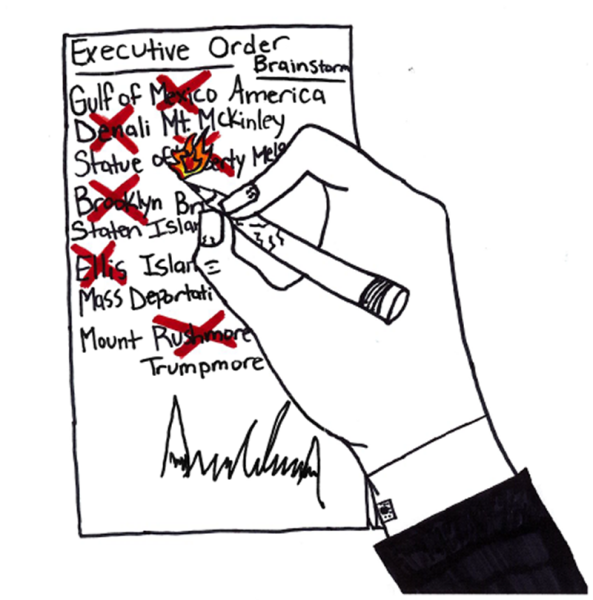

In addition, adults need to model what they teach, in school and out. I’m not so worried about teachers, though; it’s more our elected officials.

Isn’t it bullying when a governor’s aide create a traffic jam for political retribution? Or when, standing in the Capitol Building minutes after the State of the Union, a congressman threatens to throw a reporter “off this f—–g balcony”? This cutthroat political culture no doubt aggravates the problem.

We should expect civility at both the schoolhouse and the statehouse.

In the end, our goal shouldn’t be to teach students that bullying is wrong. We should teach them that empathy is right. Empathy at recess and in the workplace, in the classroom and on the Internet. Empathy for total strangers and for significant others. Empathy for both the bullied and the bullies. This path is more worthwhile — albeit more difficult — than a “just say no” approach to bullying.

And, if we’re embracing IB from pre-K to Lawn Day, we need to get serious about nurturing caring students who are open-minded toward all of their peers. SGORR is already using the Learner Profile to supplement its curriculum; the more of this synergy the better.

This is all doable. We’d better hurry, though, because those creases are permanent.