Pollack is Leaving The Shaker Classroom Behind

50 years later, Pollack reflects on career, shares advice for teachers

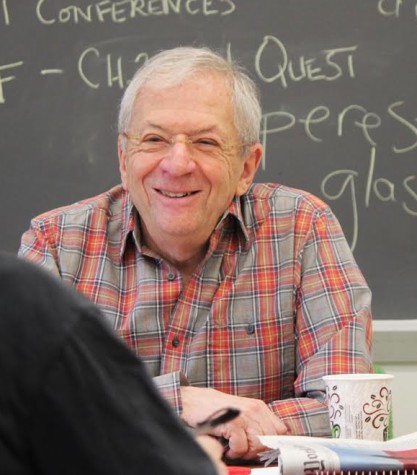

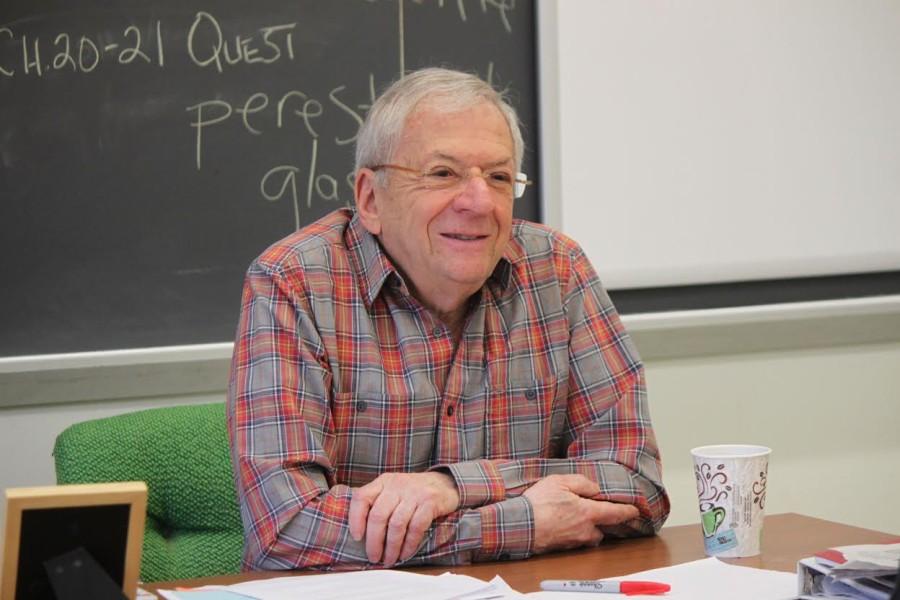

In all his years at the high school, Terrence Pollack has never sent a referral to an assistant principal. He credits this to his effort to empathize with students. Every day he observes how his students are feeling in the hallway.

“I’m probably the oldest teacher in the state of Ohio,” social studies teacher Terrence Pollack, 75, joked.

Pollack began teaching at the high school in 1964 after a three-year stint at East High School in the Cleveland Metropolitan School District.

Why retire now? Pollack said he has realized that there is a lot more of the world left to enjoy in retirement, but also points to “a number of changes in education which I’m not sure are for the best. And sometimes you feel like you no longer belong.”

He said the changes are not limited to increased testing and that the government has changed its educational philosophy.

Pollack said early in his career, teachers had the “freedom to teach. You were given the framework of a curriculum and you were basically told to teach that curriculum based upon your own strengths, your own personality.”

“We’re now caught in a framework where we have to prove ourselves based on testing,” Pollack said, adding that this limits creativity. He said this over-burdensome state and federal government interference began with the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act.

Pollack emphasized his love of students. Of his time at East High School, Pollack said: “Those kids were just as wonderful” as Shaker students. When he started teaching at Shaker, Pollack said, he “realized there really wasn’t a whole lot of difference in the kids,” and that stereotypes of inner-city kids and suburban kids in wealthy families were incorrect.

“All kids basically want the same thing. They want opportunity, they want to learn, and I also think they want to be in a classroom where there is spontaneity and creativity,” Pollack said.

Pollack proclaimed his love of teaching. “It’s a wonderful profession,” he said. “It’s the only profession I’ve ever known that you basically get paid for having a good time. Therefore you never consider it work.”

“The job of the teacher is sort of the job of a camp counselor,” Pollack said. “You develop your classroom as a cabin and give the kids a sense that we can work together and learn together and enjoy one another.”

Pollack suggested that teaching has a bad reputation. “No one ever says to a doctor, ‘When are you retiring?’ No one ever says to a lawyer, ‘When are you retiring?’ All my friends say to me, ‘When are you leaving?’ as if this is really a horrible place to be. It’s not. It’s a cool place to be.”

Pollack said teaching is “the one of the few professions in the world where you can’t ever sit back. You always have to be on top of the game. If you go to a bad movie, you can walk out. If you go to a bad class, you’re forced to stay. You’re called a delinquent if you leave.

“We have to understand that part of our job is to entertain the kids so that they want to stay with a script called subject matter.”

When Pollack feels he has failed to entertain his students, he lets them know. “Every once in a while, I teach a lousy lesson. At the end of the lesson I always apologize to my students. I say, ‘Man, this lesson really was bad. I’m so sorry. Tomorrow, I’ll try to make it better,’ ” he said. “Teachers, by nature, have to always be irritated that today’s lesson was not good enough. Tomorrow’s have to be better.”

Junior Allie Jeswald took Pollack’s Human Relations class this year.

“He’s a very good teacher because you can tell he loves what he does. I think that’s really important,” she said. For this reason, Jeswald said Pollack was good at motivating students in her class. “When you can tell a teacher doesn’t want to be teaching, it’s really discouraging to students,” Jeswald said.

Pollack said teachers should also “convey to kids that you’re here because it [the school] is a wonderful place to be . . . Kids really respond to staff who care. Kids respond to staff who say ‘please’ and ‘thank you.’ Kids respond to staff who don’t yell.”

Pollack shows how much he cares for his students by waiting in the hallway between periods to “see my kids as they’re coming into the classroom.” He said he has done this every day since he began teaching to observe “ ‘How are they today?’, ‘Who can I call on today?’, ‘Who’s in a bad mood today?’ ”

In all his years at the high school, Pollack has never sent a referral to an assistant principal. He credits this to his effort to empathize with students. He said it’s important for teachers to realize that even if they disagree with students, they “can still live in a world together.”

He said he “was hired to teach the lowest level classes because they presumed because I came from the Hough area [of Cleveland where East High School is located], I could only teach the lower-level kids.” Pollack has consciously only taught one AP class — U.S. History — and all the rest CP. “I don’t believe that it is correct for a teacher to teach only upper-level classes,” he said. “You get a skewed view of the school. It’s important for all kids to have good teachers.”

“Some people give Shaker a bad rap,” Pollack said. “They don’t see it the way it really is. They don’t see it as a mini university with multiple offerings in every department. The opportunities for kids here are enormous. Shaker has to do a better job of selling itself image-wise” in order to keep attracting families.

He believes the high school’s image is mired by state report card grades and national high school rankings. He pointed out that districts with as much socio-economic diversity as Shaker schools typically don’t perform as well in these measures, as the district emphasized during its levy campaign and when the state released its report card. Pollack said the district should invite news organizations to cover more positive developments in the schools and purchase ads in newspapers.

Pollack also wishes the district had asked voters for a bigger levy to increase teacher salaries and the level of technology in the schools and provide low-income families with computers or tablets.

Teachers, by nature, have to always be irritated that today’s lesson was not good enough. Tomorrow’s have to be better.

— Terrence Pollack

In addition to the negative report card grades and rankings, Pollack said people also see the increasing number of African-American students as a negative trend. “Just because there’s been a racial change doesn’t mean there’s been a drop in the quality of kids in the school. That’s a stereotype that must be defeated not only in Shaker, but in the U.S.,” he said.

Pollack said of the eastern inner-ring suburbs of Cleveland, the “Shaker [school district] is one of the only true success stories” because of its ability to effectively teach students who exhibit a wide variety of needs.

Pollack did mention one high school trend that he would like to see reversed: a diminishing level of school spirit. Pollack said the school used to have a dance every Friday night, teachers used to run a carnival in between semesters and the social studies department had monthly assemblies to educate students and faculty on current events. “There was a sense far more that it was a fun place,” he said.

In addition to his long teaching career, Pollack has an impressive number of accomplishments outside of the walls of school buildings.

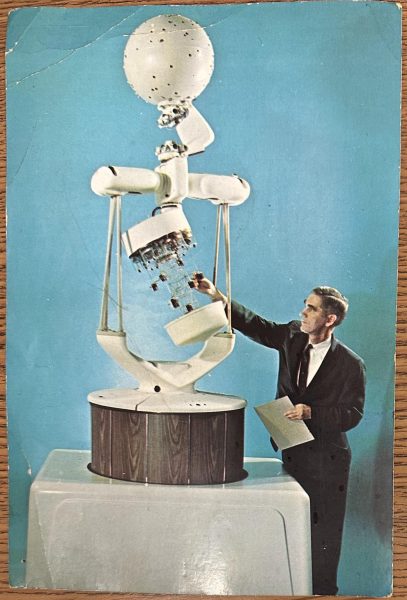

He left teaching for seven years in the 1970s to host a syndicated educational TV show for the local PBS station, WVIZ. He compared the show, which covered everything from organic foods to Congress and the Supreme Court, to the CBS newsmagazine “60 Minutes.”

Pollack has also been active in the Jewish community, directing the Association of Reform Zionists of America, a pro-Israel advocacy group, for seven or eight years, and the Anti-Defamation League’s A World of Difference program for five years, which develops training programs to “confront racism, anti-Semitism and all other forms of bigotry” according to its website. Pollack started working for the Anti-Defamation League in 1995 when he retired from full-time teaching and started teaching part time.

For the past nine years he has served as director of general academics and middle school coordinator at The Agnon School, a private Jewish school in Cleveland. He has also volunteered time on weekends as a regional director of the North East Lakes Federation of Temple Youth, a Jewish youth group, for almost 30 years.

Pollack assisted then-Case Western Reserve University Professor David Van Tassel in brainstorming ideas for National History Day before Van Tassel started the competition in 1974 in the greater Cleveland area. Every SHHS student enrolled in AP U.S. History is now required to complete an NHD project.

Pollack said he also came up with the idea of after-school study circles at Woodbury, the middle school and high school to give students additional instruction for high-level courses. Working with Principal Michael Griffith and English teacher Paul Springstubb, Pollack created Asian Studies, an after-school course that covers the histories and cultures of India, China and Japan, usually with an annual international trip to a sister school for cultural immersion. The course is offered to Shaker and Beachwood students. He also created Oppression, a course that primarily studied slavery and the Holocaust. Too few students signed up for the course for it to continue this year.

In all, Pollack estimates that he has worked with “well over 45,000 young people” in his lifetime.

“When I think about the gift that Terry Pollack has been to Shaker Heights High School, and the lives of countless others, I can’t help but smile,” Griffith said in an email interview. “Terry has an endless energy that is addictive, boundless curiosity, and absolutely no fear about experiencing the unknown. He is, bar none, among the most insightful and engaging teachers I have ever seen.”

“Whether standing in front of a class, or in the authentic moments on the back roads of China, Japan or India, we have all been touched and challenged by Mr. Pollack’s wit, humor, his keen intellect and masterfully articulate thoughts about people and the world around us. He will be greatly missed, but his influence remains here through the many programs he helped establish to close the achievement gap, build cultural competency, and teach us about understanding humanity and the global perspective,” he said.

This story appeared in Volume 85, Issue 1 (June 2014) of The Shakerite on pages 14-16.

Laura Barnett Webb | Jul 8, 2014 at 10:33 am

Terry was my teacher, colleague and above all, inspiration! He taught me to love history, appreciate my religion and culture, and encouraged me not to put up with b.s.! Is impact on thousands of Shaker kids over the years is immeasurable. Congratulations on your retirement, Terry, and enjoy!

Joel Libava | Jun 9, 2014 at 6:33 pm

I must include my thanks, to Terry.

He was in charge of NELFTY. I was a member in the late 70’s, and some of the best times of my life were when I was involved in that great youth group.

Terry was our fearless leader, and he was a great man to have around-fun and fair.

Joel Libava

Cleveland

Matt Wall | Jun 5, 2014 at 10:32 pm

Best wishes to you Terry – amazing career and I am not surprised in the least you’re still a gadfly. Rest assured some of it rubbed off. Onward and upward.

Matt Wall ’82

Candace Giddings Laryea | Jun 5, 2014 at 7:11 am

I took Mr. Pollack ‘ s class in the mid 80’s and he was among the best teachers of my high school experience. He had boundless energy and was committed to excellence. Thank you Mr. Pollack!

Sincerely,

Candace Giddings Laryea, MD

Celia Hollander Lewis | Jun 4, 2014 at 5:35 pm

Thank you for printing such an in-depth portrait of a lovely charming and intelligent man. I was a student of Terry’s, and was fortunate to know him through NELFTY as well as appearing once on his TV show. He has has a lot to do with shaping the culture at SHHS and I hope his influence holds on for generations to come.

Beth Lane Brennan | Jun 4, 2014 at 10:02 am

While it is certain that I was not Mr. Pollack’s best student in 1969, it is equally certain that he was my best teacher. He taught me to think critically and to question. I am now an Associate Dean at a university in California. Our job is to train teacher candidates. If we can train teachers who love what they do as much as Mr. Pollack, our schools will be better places!

Michael J. Saltzman | Jun 4, 2014 at 7:52 am

I graduated from Shaker in 1963, the year right before Mr. Pollack started at Shaker. His career provides an easy answer to the age old question, “Who was your favorite teacher?” Can anyone imagine asking that question to someone who was home schooled? The Shaker students will miss Mr. Pollack, I know I would.

Cheryl Cohen | Jun 4, 2014 at 12:16 am

I remember Mr. Pollack chaperoning us in Florida over spring break. We all had a blast! I also remember him telling us he had a dog named Damn It, “Damn It, get off the couch!” He was a wonderful teacher, mentor and friend. Those that had him as a teacher were indeed lucky. Good luck on your retirement…you deserve it!

Julia Bricker | Jun 3, 2014 at 11:49 pm

I took Mr. Pollock’s “Oppression” and “Human Relations” classes my sophomore year of high school, in 1998-1999. He opened my eyes and really taught me how to think. His classes awakened many passions that I still have today and led me to pursue a Bachelor’s degree in psychology and later a Master’s degree in education. He took the time to connect with us, as individuals. I am a classroom teacher now myself, and throughout my education and career, when asked to think of a teacher who made a difference, I always think about Mr. Pollock. Thank you, Mr. Pollock! – Julia Bricker

Renee Morris Roth | Jun 3, 2014 at 11:22 pm

Terry Pollack was one of the best teachers I ever had! He is a jewel to the Shaker Schools. He was also an incredible Youth Group advisor. Wishing him the best of luck and happiness in retirement!

Dana Adler | Jun 3, 2014 at 8:28 pm

Excellent article. We send our best wishes for your adventure, whatever that may be. Dana and Ira Adler