Teachers in Chicago recently ended a strike against their district’s new teacher evaluation system and its reliance on student performance. Shaker’s own teacher evaluation model is undergoing similar revisions due to a new state law and affiliation with a government program called Race to the Top.

Following the passing of House Bill 153 last year, the Ohio Department of Education mandated that 50 percent of teacher evaluations be based on “teacher performance on standards.” These standards include learning environment, instruction and professional assessment and growth. The other, more controversial half of evaluations must be determined by student performance, judged by standardized test results. Prior to the change, teachers were evaluated in five categories, including their own performance and certification.

There is disagreement about the accuracy of test scores’ portrayals of student growth. The Washington Post reported in 2011 that scoring errors are continual problems in the complicated system, and many people see standardized testing as a profit-seeking industry above all else. Students are dubious about the emphasis on student performance as well. “[T]he idea looks good on paper, but other factors besides the teacher’s ability to teach can affect test scores,” said Leah Greggo, a sophomore.

Senior Natasha Anderson agreed, adding, “It may help teachers plan a more focused curriculum, but . . . Shaker has a very worldly curriculum, and I think that is more important than learning to a test. Also, some students may not be good test takers, but are great students and learning the material. Basing a teacher’s salary or employment off of standardized tests doesn’t seem fair to the teacher.”

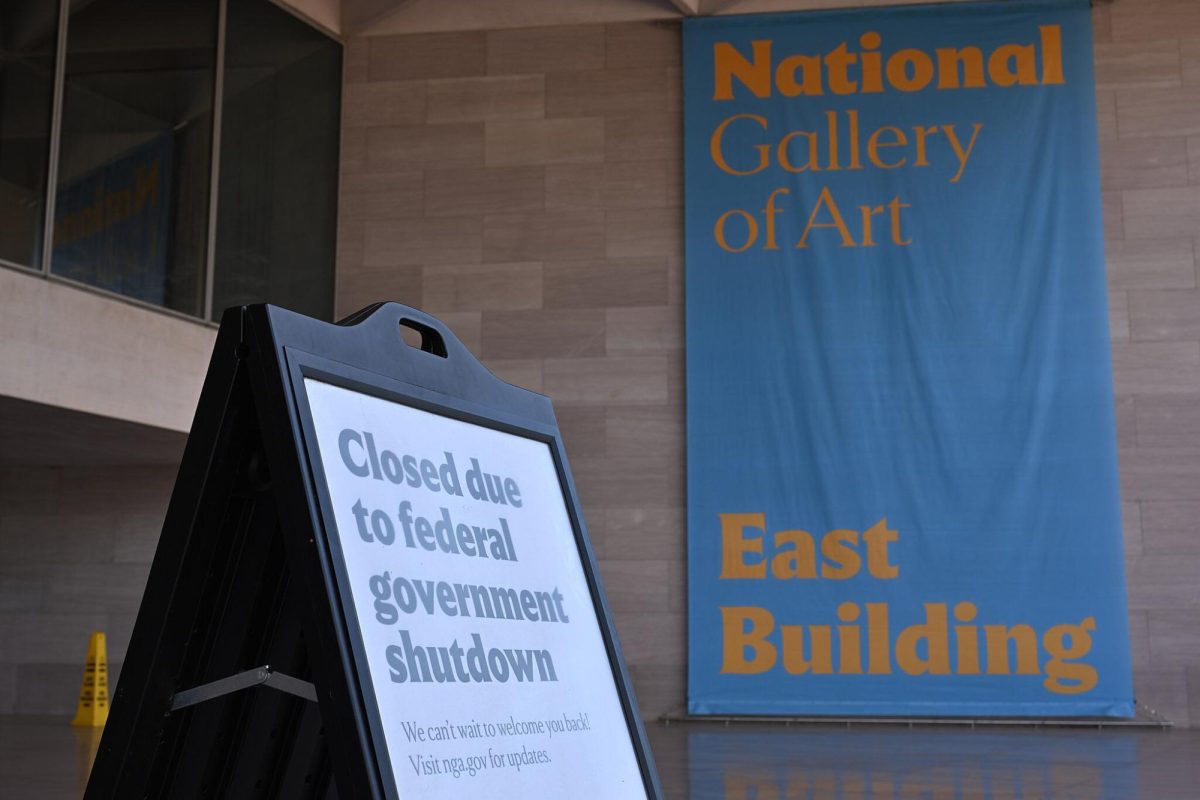

The revised teacher evaluation system must also take into account Race to the Top, a federal program promoting advances in education across the country. According to a White House press release on Nov. 4, 2009, Race to the Top is designed to be a competition between states, in which schools in states with the most improvement in education are allowed to apply for funding through the $4.35 billion fund. Schools that receive funding from the program enact the mandated reforms. Shaker, which became a part of the federal program in the past year, will revise its teacher evaluation program accordingly.

Shaker’s new evaluation process is being developed by the Teacher Evaluation Team, which last met in 2003, to create Shaker’s current evaluation system. The committee comprises a select group of administrators, teachers and school board members who have had “very positive reactions among each other,” said Principal Michael Griffith. He is a member of both the Teacher Evaluation Team and the joint Performance Compensation Committee, which is developing a mentoring program for faculty members.

According to the ODE’s website, Ohio’s new evaluation model is meant to “provide educators with a richer and more detailed view of their performance, with a focus on specific strengths and opportunities for improvement.”

Local teachers and administrators, however, are not so sure. “There are good parts of [the new teacher evaluation process] . . . Certainly pushing teachers towards self-reflection is good,” Griffith said. However, he believes that problems could arise if the new law becomes “over-burdensome, [and] people look to cut corners” due to the added responsibilities, especially for administrators.

A New York Times story portrayed the experience of Will Shelton, principal at Blackman Middle School in Murfreesboro, Tenn., which implemented Race to the Top in 2011. Shelton spends hours doing paperwork in his office, and the series of conferences he must have with each teacher takes a minimum of an hour and a half by itself.

Social studies teacher Andrew Glasier, co-facilitator of the Teacher Evaluation Team and the Performance Compensation Committee, took a more aggressive stance than Griffith. “The new evaluation process that the state is mandat[ing] with student performance will fail,” he said. “Every student is different, has different needs, different abilities and the process to figure out his/her performance and link it to a specific teacher is a logistical [nightmare] that drains the coffers of already stressed schools’ funding.”

These concerns are what drove Chicago’s teachers to the streets. While increased benefits and salaries were among the additional issues of concern, the Chicago Teachers’ Union argued that the new teacher evaluation system in particular would be unfair because it does not consider external factors which may impact student performance, according to the Associated Press. A settlement has since been reached, offering compromises on all issues.

Despite similar fears, Glasier is confident that Shaker’s teachers are not going to copy their Chicago counterparts any time soon. He “believe[s] the country will see many more teacher strikes in the future. . . . In Shaker, however, we have [a] very educated electorate and school board who understand these policies are foolish for education and have been working with teachers to minimize the damage from them.”

Separately, Glasier said, “I think Shaker school[s] will continue to push their students and work to improve education and worry as little as possible [about] politicians who believe they can do our job better.”

A version of this article appeared in print on 3 October 2012 on page 9 of the Shakerite