“It felt like a dream.”

Sophomore Brandon Bey remembers his elementary school trips to the high school, where he and his classmates met the stars and planets, courtesy of Planetarium Director Bryan Child.

Shaker students visit the planetarium twice a year throughout elementary school. Dozens of younger students line up in front of the science wing for one of their first high school experiences. Inside the planetarium, Child provides interactive presentations of planets and stars, often using beach balls to model relative sizes of celestial objects.

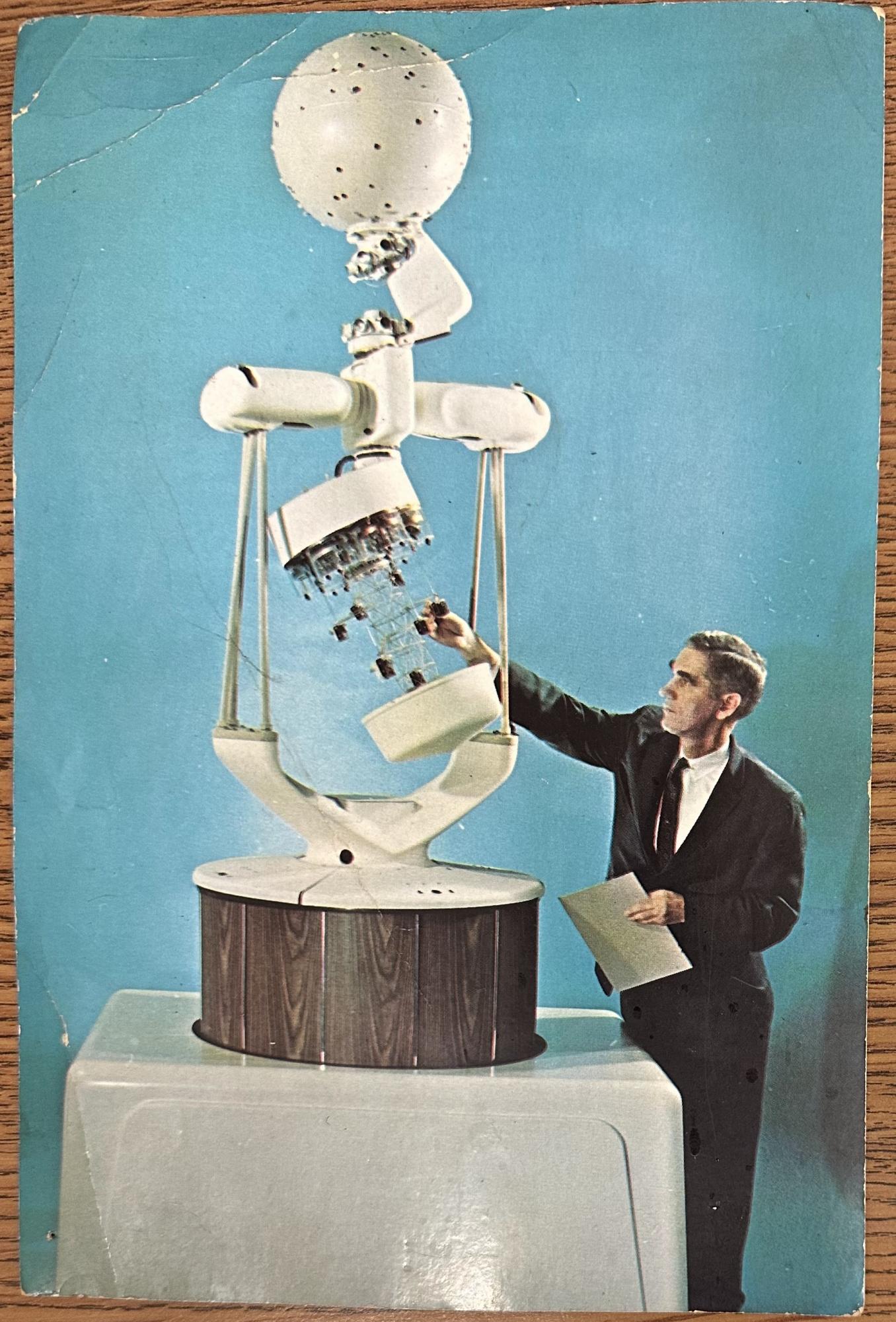

These elementary school memories have been made since the planetarium was constructed as part of a new science wing completed in 1970. The dome is made of aluminum with small holes punched in it to improve air circulation, reduce weight and allow for speakers to be placed behind the dome. The original dome projector was a Spitz Laboratories Inc. Model A4.

The A4 was primitive by modern standards. Child described it as “pretty much just a lightbulb in a can.” It used a lightbulb combined with a clever sequence of mirrors and holes to project 1,354 stars onto the dome, along with the sun, the moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. A laser pointer was used to point at objects on the dome. The operator had to manually move the sun, moon and planets to simulate their location on a specific day.

The A4 remained in use for more than 40 years. While that sounds like a long time, analog planetarium systems were built to last, and the high school’s is only one example out of hundreds of them remaining in use well into the 21st century.

The A4 was also easy to maintain. The high school paid Spitz around $3,000 a year, according to Child, to send a technician out annually to provide routine maintenance. If a part failed unexpectedly, former Planetarium Director Gene Zajac would perform many repairs himself. If he couldn’t fix it, Spitz would.

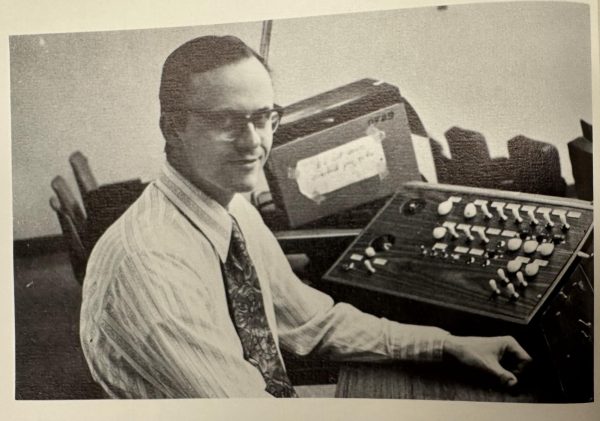

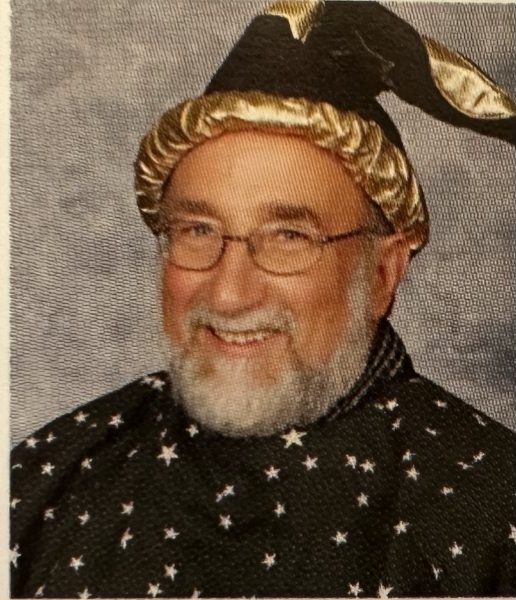

David Sandford was the high school’s first planetarium director. He operated the planetarium from its opening until his passing in 1988. Zajac, then a 6th grade teacher, became the second director. During Zajac’s tenure, Robert Sylak and Child joined him as astronomy teachers. Sylak retired in 2009, and Zajac retired in 2013, leaving Child as the current planetarium director. Dana Mercier also taught astronomy classes from 2013 through last school year.

Throughout the years, additional hardware was added to supplement the A4 projector. Six slide projectors were mounted on poles on the left, center and right at the back of the room, in order to project images across the dome. “If I wanted to create a swirling nebula, I had a special projector that would do that. For the changing of the sun from a cloud of gas to a star to disappearing and shrinking down, there was a special projector that did that,” Zajac said.

Zajac could mount carousels of photo slides into the projectors and cycle through them remotely from his control console. Later, a video projector was added alongside the slide projectors. Zajac used a computer to create and edit videos for presentations.

Zajac said he put a lot of thought into finding clever ways to enhance presentations. Once, he set up a convex mirror that he pointed a reel-to-reel video projector at, causing the image to be reflected up onto the concave dome, filling more of the dome with the image. “It was a lot of fun to rig things up,” Zajac said.

During the late 2000s, Zajac, Child and Sylak spoke with the district about a new dome projector. “Five or six years before [Zajac’s retirement], Brian and I talked about a new star machine. We met with people, and the school system was not interested. And I always told them, ‘If you get me a new star projector, I’ll stay.’ So when they finally did, they said, ‘Does that mean you’re gonna stay?’ ”

“ ‘Nope. That ship’s sailed,’ ” Zajac told them.

The new projector, a SciTouch HD, also designed by Spitz, was installed in September 2013. The SciTouch HD is a world apart from the A4; it’s fully digital and employs two projectors, one for each half of the dome, displaying a combined resolution of 1920 x 1920 pixels. Not impressive today, when TVs commonly offer a resolution twice that or above, but much more so 10 years ago.

The A4’s analog control console was replaced with two computers, one used to run and control the dome software, and the other dedicated to processing the real-time 3D imagery that the software can create. The “Touch” part of the name comes from another new feature. Instead of using a basic laser pointer to point at objects on the dome, the new unit includes a custom infrared pointer that interfaces with the software to both display a pointer and allow the operator to select and interact with objects on the dome.

The A4 may have lasted 40 years, but the SciTouch HD very likely won’t. In the 11 years since the SciTouch HD was installed at the high school, it has been discontinued and replaced with newer models. According to Child, the custom software package the SciTouch HD’s computers run has not been updated since January 2016, only three years after the dome hardware was installed, and there are no plans for future updates. The software runs on Microsoft Windows 7, an operating system that has been unsupported since January 2020. The latest full-dome movies are only available in a format that the current software does not support and now require manual format conversion to play.

Another factor to consider is the hardware itself. Component failures in systems as complex as the SciTouch HD are inevitable, and several have occurred in the nearly 11 years it has been in operation. One of the two main projectors broke down and had to be sent to Spitz for repair. The dome’s LED lighting has failed twice, both times caused by defective controllers. A hard drive inside of one of the computers failed, requiring a replacement to be sent by Spitz. Most recently, a power cable running to the projector unit was found to have begun to melt and had to be re-wired, Child said.

Maintaining analog hardware like the Spitz A4 over decades of use is possible with proper routine maintenance, but keeping digital equipment going is more difficult. Replacement parts have been available so far, but they likely will not always be, especially in cases where parts are fully proprietary. Digital hardware only becomes more unreliable as more time passes, adding to already high repair costs.

The district did not continue their yearly contract with Spitz after the SciTouch HD was installed, as costs would have risen to around $10,000 per year, according to Child.

With this in mind, along with the fact that the high school will likely be either renovated or replaced in the not too distant future, what are the district’s future plans for the planetarium? “There are none,” Child said. Funds to sustain the planetarium can come from the district and from the Shaker Schools Foundation. “It’s weird the way the school funding works. The foundation can’t buy chairs, but they can buy the projector, so there’s this weird line of who can buy what. So I would have to go to either the Shaker Foundation or the district and say, ‘Here’s the problem, here’s the price, how do we want to handle it?’ ” Child said.

Dr. John Moore taught science at the high school before becoming director of curriculum and instruction. “I think we take a lot of pride in our resources and facilities here, and the planetarium makes Shaker really special. When I think about some of the highlights of a Shaker education, I think about something like the planetarium that is really accessible K-12,” Moore said.

While Moore finds the planetarium valuable, he stresses that the community’s opinion is most important. “You have to really engage people to know what they value. My responsibility is to be responsive to the needs or desires or wants of our community.”

When the time comes, Moore said he plans to work with Child during the decision process.

Child said that there is no current need to replace the dome hardware, but he expects that the time will come “at some point in my career, just because these systems do have somewhat of a lifespan.”

The community and district will determine how many more students will carry planetarium memories with them after graduation. Freshman Maylin Heiskell recounted hers. She said, “We would all think we were big kids, since we were actually in the high school. When it was my first time ever going, it felt like I was in space.”

Daniel Carroll contributed reporting.