Solving More Than Equations

Building jigsaw puzzles together helps math teachers unwind

Imagine that it is seventh period; you have been answering the same three questions repeatedly throughout your day.

You are tired, hungry and exhausted by the continual chatter from all of your classes. You need a break. For the Math Department, the solution is simple: puzzles.

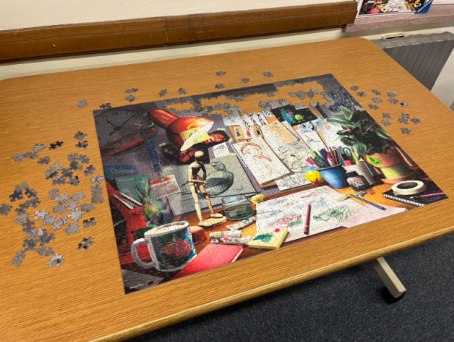

During first period, I journey down the hallway to Room 214, a small space that houses the Math Department’s office. To the front of the room sits 9th grade math teacher Adam Thomas. His fellow freshman math instructor Walter Slovikovski sits along the left wall, and stationed to his right is Calculus teacher Lori White. They work hastily, answering emails and composing lesson plans. If they finish tasks with time to spare, they can work on their newest puzzle, a rendition of a busy desk.

The puzzles provide more than a distraction from lesson planning and grading; according to White, the jigsaws actually make her work more productively. This feeling can be attributed to the fact that puzzling has been proven to offer many cognitive benefits. A 2017 study by the National Library of Medicine found that “jigsaw puzzles can help improve visual-spatial reasoning, short-term memory, and problem-solving skills as well as combat cognitive decline, which can reduce risk of developing dementia.”

The perks of puzzling do not end there for White, however. “For me, it is also more of a relaxing thing. If I am stressed about something, I can come in and work the puzzle and it kind of takes it off my mind.” Not only do the puzzles provide both cognitive and mental health benefits, they also offer an external motivation for math teachers to finish their work on time. “I’ll get my work done, and then I’ll come over here and start looking for pieces,” White says.

The puzzle currently occupying the back table is near completion; the upper right corner remains unfinished. White quickly explains why: “You can see the part that we have left is all of the gray area.” Apparently, even college-educated problem solvers can be tripped up by the monochromatic nature of a jigsaw puzzle.

Puzzling in the Math Department originates from Michael Kabay, who teaches Algebra II and Precalculus. Kabay saw the game as a fun way to challenge his colleagues – at first, he hid the puzzle boxes. The rest of the department found an easy workaround however: looking up the puzzles online and printing images of their boxes.

Puzzling in the math office is a welcome new addition, White notes. “People come in for five minutes, and are able to get away from things and get out of their heads,” she says.

“Who is the best puzzler in the department?” I ask. Slovikovski suggests reading teacher Kady Cole, whose classroom neighbors the math office.

“I am like an honorary member of the Math Department, basically because of geographical setting. I’m next door to them,” Cole said in an interview. She disagreed with Slovikovski’s assessment and suggested that Kabay is the title’s rightful holder. “I’ve witnessed him just go and not even use the box, just stare and put pieces together,” she said.

Cole attributed her puzzle prowess to her enthusiasm and previous career as a commercial interior designer. “I did a lot of space planning, and that was puzzles, so I’m very visually oriented,” she said.

“Mr. Kabay is pretty good, as well,” Thomas says. “Mrs. White needs to give herself some credit, too.”

“I’m very determined,” offers White. “When I start a puzzle, I have to finish it.”

Web Design Editor Josh Levin contributed to reporting.