Fighting for the Right to Kneel

Community members, teachers, students related to armed forces discuss kneeling controversy

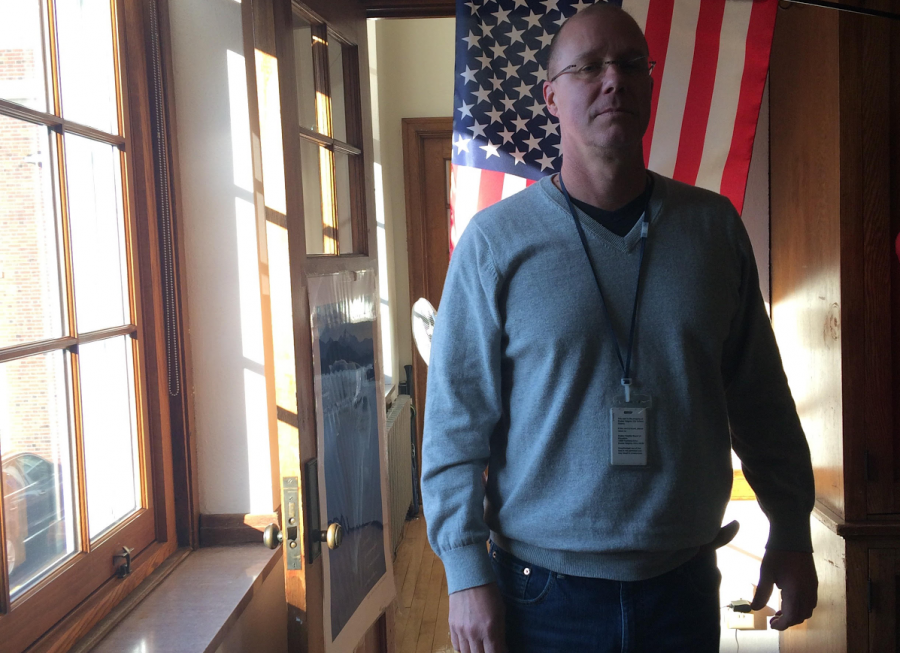

Tod Torrence, Army veteran and history teacher, in front of his classroom’s American Flag.

Though he stands for the national anthem, Tod Torrence has no objections for those who do not.

“I think, overall, Colin Kaepernick’s idea of drawing attention to social injustice issues in our nation was a good idea,” said Torrence, a history teacher and Army veteran.

Although as a child Torrence was taught to stand during the national anthem — and still does — he supports the protest and its cause. “We still have a huge problem with race in our country, obviously being further exacerbated by our current administration,” said Torrence, referring to U.S. President Donald Trump.

Shaker students have knelt during the national anthem at sporting events, modeling their support for the Black Lives Matter movement after former National Football League quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s protests. Kaepernick was the first professional athlete to kneel during the anthem. His protests have spread among other athletes in other sports at professional, collegiate and high school levels since 2016.

Students have knelt at football games, soccer games and other sporting events. Even some spectators at the hockey game Dec. 2 did not stand when the national anthem was played. When marching band members were given permission to kneel at a football game, a teacher notified them that they might be subjected to harassment or even violence.

This form of protest has sparked debate around the country. Those who oppose kneeling claim it is disrespectful to members of the armed forces.

“I fought for the right to kneel,” said Chris Roessner, an Iraqi War veteran who grew up in Ohio and visited the high school Nov. 9 to speak to the Political Action Club. Roessner said he could not speak for veterans everywhere, but he considers such protests patriotic uses of the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech and assembly. Two Shaker residents associated with the armed forces expressed similar opinions during interviews.

Senior Emma Ponitz plans to join the Marines after graduation. She supports those who choose to kneel during the national anthem but does not participate in those protests. “I think that I didn’t kneel because — not that I didn’t feel a strong enough pull towards the cause — but I thought that for me, personally, I want to make a difference in a different way.”

“I think people get confused about why people are kneeling,” she said. Ponitz said that though opponents of kneeling claim it is offensive to the military, the protest is not about the flag. Ponitz sees the protest for its objective: to bring awareness to institutional racism in America.

“I’ve seen veterans who are really supportive of kneeling, who, like myself, see that it’s not about disrespecting the flag, that it’s about greater issues,” she said. Ponitz believes that veterans sometimes oppose the protest because the flag holds sentimental meaning to them. The flag is placed over the coffins of veterans as a sign of respect for their service.

“I understand that they want people to bring awareness to the issues in different ways,” but the athletes protesting are not making any statement about the flag, anthem or veterans of the armed forces, she said.

Torrence comes from a family of veterans, and their perspectives on the protest differ. “My father, a veteran of the Korean War, he’s not happy about it, but he’s not going to stop watching football games,” he said. “My brother’s a 22-year Air Force veteran, and we’ve talked about this and it doesn’t offend him.”

Torrence’s children attended the high school. Though these protests did not occur at their time in the high school, if they had, Torrence said that he would have supported them. “I would say that’s your right,” he said. “As an individual, you can make those kinds of decisions.”

Torrence said, “As a veteran myself, I’m going to stand and put my hand over my heart anyway. But what other people do is up to them.”

Comment using your Facebook, Yahoo, AOL or Hotmail account