What the Refs Don’t Hear

Racial bias and offensive language target Shaker’s African-American athletes

Racism in sports isn’t anything new.

African-American baseball pioneer Jackie Robinson faced death threats in the late 1940s. Former Los Angeles Clippers’ owner Donald Sterling didn’t want his girlfriend to bring her African-American friends to the team’s games in 2014. In Europe, fans throw bananas at African-American professional soccer players.

And on Oct. 13, 2017, African-American Shaker football players were called “porch monkeys,” according to junior running back Rasheen Ali.

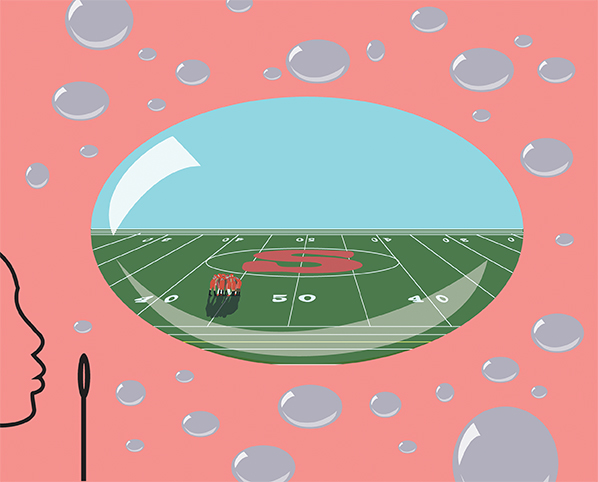

Shaker is known for being a racially diverse, progressive community. Yet, not even the Shaker bubble can protect our African-American athletes from offensive, racist language.

On that night, Shaker’s varsity football team trailed the Strongsville Mustangs by four points when senior Jamir Dismukes, an African-American quarterback, ran into the endzone. The scoreboard showed three seconds left, and the Shaker crowd and marching band erupted in celebration.

However, the referees had thrown a penalty flag on the field to call an unsportsmanlike conduct penalty on Dismukes, who, en route to score, had altered his stride into a brief high-step with no opponents nearby. That action constitutes unsportsmanlike conduct, according to the Ohio High School Athletic Association rulebook. Because unsportsmanlike conduct is a dead ball foul, or a penalty called after a play ends, a 15-yard penalty is to be administered before the next play, rather than negating, or “calling back” the previous play.

However, instead of moving Shaker back 15 yards for the following extra point attempt, the referees took away the game-winning touchdown.

Earlier in the game, the same situation occurred. Senior Sam Meinhard, a white linebacker, was flagged for unsportsmanlike conduct after a Raider touchdown. With that call, the referees let the touchdown stand and correctly applied the 15-yard penalty to the following extra point attempt.

Athletic Director Don Readance said that the second unsportsmanlike conduct call was especially frustrating because the officials had applied the rule correctly in the same scenario earlier in the game.

“They counted the touchdown in that situation and they moved the point-after 15 yards back. For some reason, they misapplied the rule at the end of the game,” Readance said.

Readance said that the reason for the blown call might be the race of the offending players; the officiating crew was all white, and the Strongsville team had only three African-American players. “If I had to place a bet, and I’m not a betting man, I do think there was some sort of bias in that call,” Readance said.

The two plays were almost identical. Each penalized a Shaker player for unsportsmanlike conduct following a touchdown. However, the call at the end of the game was on an African-American quarterback, taking away a win from Shaker, a team with only three white players.

Readance sent a video of the penalized play to OHSAA Assistant Commissioner Beau Rugg, who admitted that the call was incorrect and informed Readance that sanctions were leveled against the officials.

“[The officials] were removed from playoff contests that they were supposed to work for this year and they might be put on probation for next year,” Readance said.

Although losing teams and their fans are known to rationalize defeat by blaming officials, the officials’ act in this case did lose the game for Shaker. And we cannot know whether race played a role in the mistaken application of the unsportsmanlike conduct rule. But Shaker athletes more often experience racism through comments from opponents, most of which go unnoticed by officials, than from controversial calls.

Ali said that during the Strongsville game, players called him and his teammates “porch monkeys,” a racial slur, in between plays.

The term originated in the south in the early 1900s, when African-Americans started building bungalow-style homes with front porches. The phrase is a derogatory term for African-Americans; it implies that they are lazy and have nothing better to do than to sit on their porches.

Ali added that the opponents chanted the N-word at him and his teammates, but the referees couldn’t hear this abusive language because Strongsville football players uttered it while Shaker players were on the ground.

Shaker football players said that their Strongsville opponents used racial slurs in their Oct. 13, 2017 game.

Senior tight end Billy Dunn, who is biracial, confirmed that he heard Strongsville players calling his teammates the N-word. He added that they called him a “n*****-lover” when he was close to their sideline.

Andy Jalwan, Strongsville’s athletic director, did not respond to request for comment in time for publication.

School counselor David Peake said he was surprised when football players came to his office and casually mentioned that Strongsville players called them the N-word. He explained that these players came to him to talk about their unfair loss, not the racist language.

“Students didn’t come to me to report it. This is what is really alarming. They didn’t come to say, ‘Hey, we were getting called the N-word.’ They are so used to it that to them, it wasn’t even a concern,” Peake said.

He added that athletes have previously come to talk to him about racist language used by opposing teams. “I hate the fact that young men that are a few years younger than me have to accept that like it’s a part of the game,” he said.

Junior cheerleader Erin Harris said she saw Strongsville students displaying fake gang signs during the game and that a friend overheard racist insults about Shaker.

Harris said, “One of my friends was at the concessions line and a boy said, ‘You need to say ‘Yo, dawg’ when talking to [Shaker students] because they don’t speak proper English over there.’ ”

In a letter to Rugg and former OHSAA Commissioner Dan Ross, Readance raised the possibility of requiring officials to watch a video that would enhance their ability to deal with diversity. “There are prejudiced people everywhere. To think that all officials are fair and not biased is just foolish,” he said.

Rugg and Ross invited Readance to Columbus to discuss his idea.“I feel good that they had me come down and that they took my letter seriously,” Readance said. “Whether or not they implement something with regards to cultural sensitivity training for officials — it’s something I will follow up with them to see that something comes to fruition.”

Peake, who advises the high school’s student branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, said the club is also advocating for diversity training for officials.

Peake explained why the controversial call is an example of structural racism. “We have someone that scores a touchdown, and then you take the touchdown back. The penalty for that is not taking the touchdown away; the penalty for that is something else. In my opinion, that’s what structural racism looks like: Where you have this structure in place, you have people in certain roles that can exercise authority however they want to,” he said.

There is nothing in the OHSAA Officials Handbook that addresses how to handle offensive language. However, Rugg said that it’s clear to officials that it’s necessary to penalize language they deem offensive. “If you don’t penalize it, then someone else thinks that language is OK,” he said.

He also added that penalizing such language can prevent fighting or other physical responses. “In sports, if language offends somebody and [an official calls it], then it will prevent worse physical contact,” Rugg said.

He said that officials call on athletic directors to extinguish offensive chants or racist language that comes from fans, but “officials are directly responsible for those on the field and court.” Rugg also emphasized that it can be difficult to hear offensive language during a game.

In football, for example, it’s hard for referees to hear players’ language due to the distance they are required to maintain from players for safety reasons.

Referees also need to pay attention to every facet of the game. So Rugg, a former official, said that it’s common to become “tone deaf to what the players are saying” in order to focus on other details of the game.

Rugg said nonverbal cues are easier to penalize than verbal cues because officials don’t have to be close to the players to see gestures and body language. For example, it’s easier to see a player physically intimidate an opponent than it is to overhear racist language during a game.

Football players are not the only Shaker athletes who have endured racist language while competing. On April 10, racial slurs were directed at sophomore Elliot Green and junior Carlos Hill during an away junior varsity lacrosse game against Medina High School.

Green, who’s biracial, said a Medina player made racist comments toward him during a timeout. “As we were going to the sidelines for the timeout, he said, ‘Stupid n*****.’ I asked him, ‘What did you say?’ And he said it again as he was walking away,” Green said.

Green also heard the same Medina player tell Hill that he was “going to lynch him in front of a Christmas tree.”

Hill said he heard the Medina player call Green the N-word, “His teammates told him to stop, but he didn’t. Then he came over to me and called me the N- word and told me he was going to lynch me.”

Green added that Medina players told their teammate, who was defending Green, to leave Green and cover another Shaker player.

“The other defender came to guard me, and he said, ‘That kid is pretty stupid. He always argues with our coach every day. He’s got a problem, or something,’ ” he said.

Green and Hill told their coach, who then told Medina’s coach. The Medina coach suspended the player indefinitely, according to Readance.

Hill said his coaches were proud that he didn’t react aggressively. “They encouraged me to ignore ignorance and do my best on the field,” he said.

Readance explained the procedure for dealing with offensive language at high school games. “If something happens at an athletic event, the first step is the player tells the coach. Then, the coach tells the opposing coach. If there’s an official within earshot, you should let the official know, just so that nothing escalates into something further,” he said.

Readance added that the severity of the language might require further disciplinary action. “At the very least, there’s an athletic consequence. Every district is going to handle it differently, and we can’t dictate that,” he said. “Nor can anybody dictate how we discipline our kids.” Readance explained that the harsh reality of our time is that there are still racist individuals in our communities.

“There are [racist] people out there. We have [racist] people in this building. We have racist people everywhere,” he said. “I don’t know if this is because of the climate of the country, or because the politics in every age becomes more emboldened to speak out.”

A version of this article appears in print on page 44-45 of Volume 88, Issue III, published May 18, 2018.