State Formula Aims to Solve Inequity Between Foes

Private schools won 43 percent of state championships in 2009. “I think it’s about wanting to get scholarships, wanting to put yourself in the position, individually, to be seen and play for a certain coach,” said assistant athletic director Michael Babinec.

Private schools won 43 percent of state championships in 2009. Yet, private schools comprised only 16 percent of the Ohio High School Athletic Association.

The OHSAA created the Competitive Balance Committee in January 2010 to address concerns about private school domination in state championships. For example, only one of seven teams that won a 2009 high school football state championship was a public school.

The committee comprises selected OHSAA staff members, superintendents, principals and athletic administrators. It includes educators from school districts of various sizes and demographics.

“The committee has come up with different proposals to try to help with the situation,” OHSAA senior official Bob Goldring stated.

According to Goldring, all proposals are presented to the OHSAA board of directors.

Once the board approves a proposal, 820 high school principals across the state vote on it. For a proposal to pass, it needs a simple majority vote.

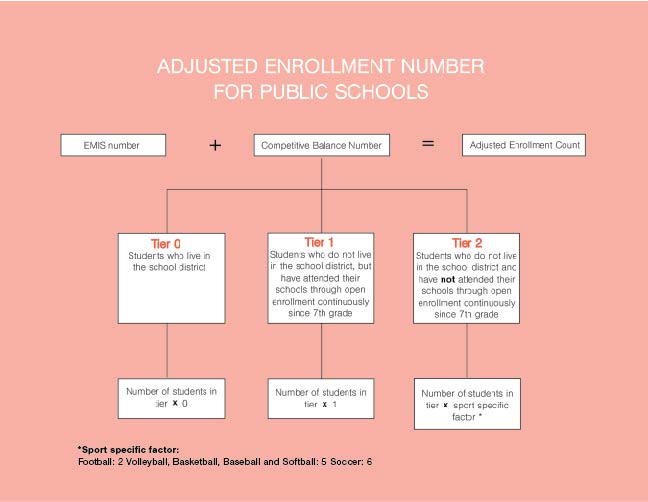

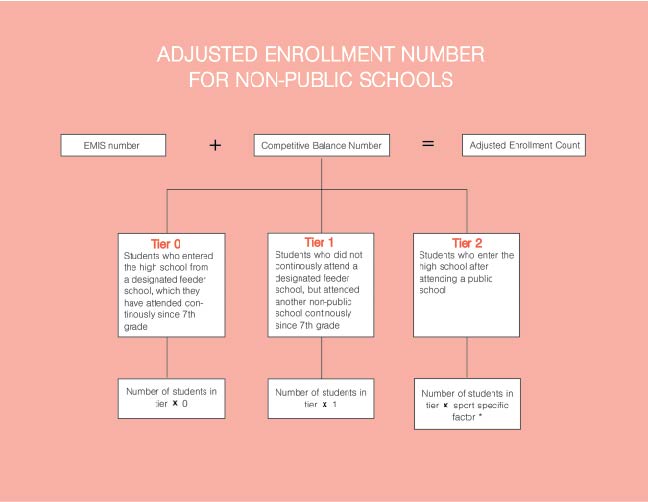

Before the competitive balance proposal passed, the OHSAA placed teams into divisions based on their state-assigned Education Management Information System number, which is the number of students enrolled in grades 9-11.

However, in a 2014 decision, the committee passed a proposal that created a new formula that calculates a competitive balance number, which is added to a school’s EMIS number.

The EMIS number for male sports is the number of male students enrolled in grades 9-11, and for female sports, the number of female students enrolled in grades 9-11.

The competitive balance number for each school, as calculated by the formula, is added to these EMIS numbers. The resulting number determines which divisions Ohio high schools compete in, Division I, II or III.

The competitive balance number is derived by categorizing athletes into three tiers by a complex set of criteria. In short, the state looks at the student’s home address and where the student attended school previously.

Each student is assigned to a particular tier based on these two factors. Then, each tier is assigned a multiplier, which is added to the school’s EMIS number to generate an adjusted enrollment count.

The formula addresses schools that attract more athletes from outside of their feeder schools, giving them a competitive advantage. Public and private high schools draw the most students from their affiliated middle, or feeder, schools.

Private schools attract more students from outside of their feeder schools, so their competitive balance numbers tend to be higher than those of public schools.

The News-Herald Mentor’s Elijah McDougal carries during the Cardinals’ victory over Shaker Heights on Oct. 7.

The formula amplifies the large gap between the largest and smallest schools in Division I.

Because Shaker does not offer open enrollment, no Shaker students legally reside outside of the district’s attendance zone. Therefore, the school’s competitive balance number is zero.

According to the Ohio Department of Education, 17.9 percent of Ohio school districts don’t offer open enrollment, which allows students to attend a school outside of their residential districts, tuition free. Sports teams at non-open enrollment schools, including Shaker, comprise only students who live in the school district.

Last year, varsity football had an EMIS number of 645. Because Shaker has a competitive balance number of zero, the adjusted enrollment count after the formula was still 645.

St. Xavier, however, had an EMIS number of 1,178 and a competitive balance number of 354, giving the school an adjusted enrollment count of 1,532. St. Xavier has won three football state championships.

Skilled athletes flock to private schools to win state titles and pursue athletic scholarships. In addition, private schools enjoy greater access to and flexibility in funding.

Bleacher Report stated, “Private schools can receive money from big-shot donors and use that money toward whatever sports programs they want.”

Private schools can use such funding to participate in more tournaments or buy more practice time on ice, for example.

Private schools’ winning athletic culture gives them an advantage over public schools, and school officials are trying to level the playing field by elevating successful Division II and Division III private schools into higher divisions.

This action is meant to give public schools in Division II and Division III an advantage by sending their strongest competitors to fight against bigger foes.

Michael Babinec, assistant athletic director, said that the point of the formula is to bump up dominant Division II and III schools such as Archbishop Hoban into higher-skilled divisions. Archbishop Hoban has won football state championships in 2015, 2016 and 2017.

Goldring agreed. “So, if multiple factors are added to school enrollment figures based on where schools obtain their team members, the result is a school will move up to a higher division for tournament competition,” he stated.

Yet, the formula doesn’t affect the placement of most Division I public schools, such as Shaker.

“When we do our competitive balance, it really isn’t a factor for us because we’re pretty much always going to be at the Division I level. We’re kind of towards the bottom end of Division I in terms of enrollment, but I don’t think we’re anywhere near benefiting from dropping to Division II,” Babinec said.

Dropping down to Division II would likely lead to Shaker’s dominance, because Division II schools have fewer students and thus a smaller pool of athletic talent.

Dropping down to Division II would likely lead to Shaker’s dominance, because Division II schools have fewer students and thus a smaller pool of athletic talent.

Shaker wouldn’t benefit from moving to Division II because the Raiders are already a competitive Division I program, having won Division I OHSAA state championships in seven different sports.

Even if Shaker wanted to drop down to Division II and win more state championships, the state wouldn’t allow it unless enrollment declined sufficiently. Falling enrollment would be harmful to the community and district, and while Shaker could win more state titles, dropping to Division II might also mean the Raiders would find themselves consistently dominating opponents.

If the Raiders were to consistently outperform teams in Division II, Shaker would lose the competitiveness that is vital to the strength of high school athletics.

Whether the competitive balance formula reduces the gap in athletic success between private and public schools has yet to be seen.

“That answer will probably be in the eye of the beholder,” Goldring stated.

“Has competitive balance made a difference? Right now that is difficult to say,” he continued. “It may just be the cycle we happen to be in.”

The cycle Goldring referred to makes high school athletics unbalanced, with athletes from all demographics flocking to successful private schools and public schools. According to Goldring, the formula can’t stop this cycle.

State championship-winning school districts attract kids because of their winning culture.

According to Babinec, the modern high school sports culture is oriented to success and individual opportunities.

“I think the mindset has changed at the high school level. It used to be a chance to play with your friends, kids you’ve grown up with your whole life, and put on a jersey that represents your community,” Babinec said. “Now this doesn’t matter as much. I think it’s about wanting to get scholarships, wanting to put yourself in the position, individually, to be seen and play for a certain coach.”

A popular public school belief, reinforced every time private schools dominate state championships, is that private school athletics are superior because private schools recruit athletes.

Neither private nor public schools are allowed to recruit athletes.

In bylaw 4-9 of the OHSAA Handbook, section one states that “any attempt to recruit a prospective student-athlete for athletic purposes is strictly prohibited.”

However, there are two specific exceptions to this bylaw.

First, coaches from a public high school are allowed to contact students in grades seven and eight who currently attend a middle or elementary school within that school district.

According to the OHSAA, the rationale behind this exception is that “those seventh-eighth grade students are already enrolled within that public school district and thus it should be permissible for coaches in that district to contact them concerning athletic participation.”

The second exception is that private school coaches are allowed to contact athletes within their feeder schools or district zones.

The handbook also states that “marketing with a solely athletic focus, regardless of the mechanism of distribution, is prohibited.”

St. Ignatius senior and former hockey player Will Sauerland, who attended Shaker schools from kindergarten to eighth grade, said that there was no recruiting process for him.

“Once they heard that I was interested in coming there, they came to one of my games and that was it,” Sauerland said.

Private school sports might be superior just because of the winning cultures they build. A successful, championship-winning athletic program is a recruiting tool in itself.

Who wouldn’t want to play for the best high school and have a chance at winning a state championship every year? The success of private school sports might be the reason they draw athletes from outside their feeder zones, not illegal recruiting.

While the competitive balance formula challenges Division II and Division III schools who draw athletes from outside their feeder zones, Division I private schools are untouchable.

They will remain in Division I no matter how many athletes flock to their schools.

So, boys will continue going to St. Ignatius to win Division I state championships. No formula will prevent these powerful private schools from filling their trophy cases with state titles.

A version of this article appears in print on pages 52-57 of Volume 88, Issue 2, published Feb. 8 2018.