Back to the Lake Erie League

Shaker plays Cleveland Heights, a member of the LEL, in a softball game on April 26.

This year marked the fourth time Shaker has switched athletic conferences since 2011.

Shaker was a member of the Lake Erie League athletic conference in 2011. Then, the district left the LEL for the Northeast Ohio Conference and competed there for two years to get a chance to play new teams and expand competition. The NOC fell apart in 2013, and Shaker along with seven other teams formed the Greater Cleveland Conference. Shaker competed in the GCC for seven years. At the conclusion of the 2019-20 school year, the district left the GCC to return to the LEL, its fourth league switch in 10 years

In its announcement of the move, the district indicated that it would leave the GCC and stated “the purpose of this change is to improve overall athletic competitiveness, reduce travel costs and better support the socio-emotional development of our students.”

A conference change comprises lots of individual changes. Some are as simple as creating a new banner listing each school in the new conference to hang in the gym. (Although it is not required the banners hang in the gym, most schools do so.)

Other changes are more complex, such as renewing scouting efforts. Once teams have been in a league for some time, they become familiar with the players, the teams’ playing styles and tendencies. Once schools change leagues, they are not as familiar with the new teams and have to prepare differently.

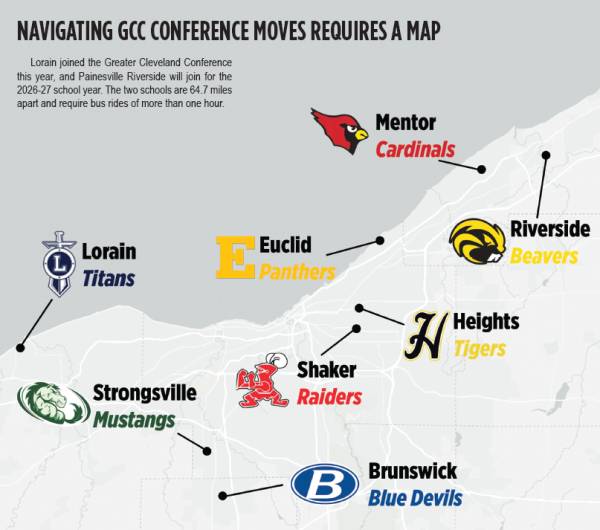

The league change also lessens the burden of time for travel on athletes. GCC teams include Medina, Brunswick, Elyria, Solon, Euclid and Strongsville. Most of those schools are not close to Shaker, creating long trips to get to and from the contest. This posed a problem on weeknights when student-athletes would come home late from a game at Brunswick or Medina and still had to prepare for school the next day. LEL teams include Warrensville, Cleveland Heights, Maple Heights, Shaw, Bedford, Garfield Heights and Lorain. Most of the teams in the LEL are close to Shaker.

Also from a competitive standpoint, switching from the GCC to LEL gave an advantage to all athletic teams, specifically softball and volleyball. Switching back to the LEL also allows Shaker to return to traditional rivalries, such as that with Cleveland Heights.

The most compelling, and disturbing, reason for the return to the LEL lies in the district’s statement about athletes’ social-emotional health. Shaker student-athletes have reported incidents of GCC athletes using racial slurs during contests. The district hopes the switch to the LEL will help to eliminate these incidents.

But why do Shaker athletes need better socio-emotional support?

Black athletes, whether they are professionals in the NBA or NFL, or in high school in the GCC, suffer from racism and discrimination when competing.

Black athletes at every level have faced discrimination and racism for as long as they have competed in sports. For example, in 2019, Oklahoma City Thunder point guard Russell Westbrook was playing a game against the Utah Jazz. He was approached by a fan near the team bench who made racist comments toward him. According to Westbrook, the fan said, “Get down on your knees like you used to.” Westbrook claims that he suffers abuse every time he plays there. Westbrook is also on video reacting to the fan by threatening him and his family. Westbrook was fined $25,000 for “directing profanity and threatening language to a fan.” The fan, Shane Keisel, was banned from the arena for life.

In 2019, Golden State Warriors center DeMarcus Cousins claimed that when he was playing against the Boston Celtics, a fan made racist comments toward him, similar to Westbrook’s experience in Utah. Furthermore, fans at European soccer games have directed racist chants at Black athletes. In Bulgaria, fans made Nazi salutes and made monkey chants. In the Netherlands, a game was stopped due to racist chants. It is obvious that racism in sports has been consistent through time. These racist acts show how Black players are treated while playing in their sport by fans, coaches and sports organizations.

Junior basketball player Danny Young, Jr. related his experiences playing against Brunswick during his freshman year. “When we were playing, I was walking to the corner, and somebody called me the N word, and everything broke loose. I fouled out and they called me the N word again. I kicked a couple trash cans and got ejected,” Young said. “I feel like [racism] is in sports a lot.”

Head men’s varsity basketball coach Danny Young cited reasons for the league change from GCC to LEL. “There were some racial issues at certain GCC games that made the decision to move back to the LEL. There were some racial tensions that were directed at our athletes during contests. I think it was the right thing to do to return to the LEL,” he said.

Young was interviewed by WKYC in 2019 about the racial slurs that were directed at Shaker players. “They were called porch monkeys and the N-word. I had kids in the locker room this year crying because they were called those names,” he told WKYC. In the interview Young also gave his opinion on the racial tensions and why Shaker left the GCC. “It’s only so much that young men can take, and you just don’t want to keep putting them in those environments where they have to be subject to that,” he said.

Young said the league switch was based on more reasons than those related to race. “We left due to location and proximity to all our games. [It] helps especially when student-athletes do not have to get home so late during weekday games. Rivalries have increased due to neighborhood games, which will help our fans be able to attend games,” he said.

The GCC schools farthest from Shaker are Medina and Elyria high schools, which are both 48 minutes away. The average distance to a GCC school is 38 minutes. The farthest LEL school from Shaker is Lorain, which is 56 minutes away. The average distance to a LEL school is 20 minutes.

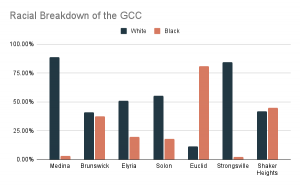

Shaker’s return to the LEL is a move away from majority-white schools and a move toward majority-Black schools. The GCC has an average of 27.18 percent Black students and 55.4 percent white students. Medina has the largest percent of white students, at 89 percent, compared to Euclid, which has a 82.1 percent Black student population.

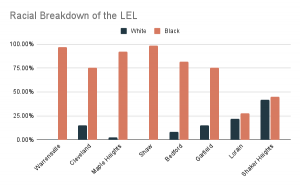

On the other hand, the LEL has an average of 78.27 percent Black students and 8.96 percent white students. Lorain is the LEL opponent with the greatest population of white students with 21.7 percent, compared to Shaw, which has a 98.8 percent Black student population.

Senior cross country runner DeAndre Hall is a minority in his sport and said GCC opponents made him aware of it. “People on my team are really cool. They accepted me as family as soon as I got there as a freshman. They welcomed me and were happy I was a part of the team. Against other teams, I get these kind of looks [from opponents] looking at me saying, ‘Why am I out here?’ or ‘Why am I running?’ They don’t think I’ve got the chance to be great,” Hall said.

Other athletes, who are white, said they were not affected by the league change as much as the Black players were. Junior field hockey and lacrosse player Maddie Lenahan said the field hockey season was not affected by the league change. “I believe some of the schools we play in lacrosse have changed, as we are not playing [Hathaway Brown] this season. I was shocked, because they are one of our biggest rivals. I do not have a strong opinion on the league switch, because it has not affected me yet,” she said.

With the lacrosse season coming to an end, Lenahan noted how returning to the LEL has affected competition. “I’ve noticed that the scores have been really unbalanced, and the competition level isn’t the same as previous years. The league change has resulted in us winning by 10 or more goals. Although winning is fun, I wish there was better competition for us to play,” she said.

Senior field hockey player Maggie Carter said returning to the LEL did not affect her much. “In the Cleveland area, there are only a couple field hockey teams, so for my sport we were not affected by the league change. We continued to play teams that we have always played, which are just the schools that have field hockey. Field hockey at Shaker and in most schools is a predominantly white sport, so we have never really had issues with treatment from opposing teams or slurs,” she said.

Despite increasing awareness of systemic racism and racial inequity, slurs directed at Black athletes persist at every level.

Coach Young said, “As you can see with the state of our country, we have a lot of work to do with racial equality.”

A version of this article appears in print on pages 54-57 of Volume 91, Issue I, published May 28, 2021.

Comment using your Facebook, Yahoo, AOL or Hotmail account