Are We Heading for Trouble?

New information about long-term brain damage magnifies danger of concussions for athletes

The high school football team plays Benedictine Aug. 31 at home.

Junior Sam Votruba started playing football this season, but his mom was not happy about it.

“The risk of concussions made my mom strongly against me playing football. She is still against me playing,” he said.

Concussions are caused by a blow to or extreme shaking of the head that shift the position of the brain, which causes chemical changes to the brain’s environment and destruction of its cells.

Most of the time, concussions are minor injuries, and athletes bounce back after rest and proper treatment. However, if the concussion is serious, it can cause permanent brain damage in the long run or, in rare cases, death.

Concussions are most common in contact sports, such as football. But Athletic Director Don Readence said that concussions can occur in almost any sport.

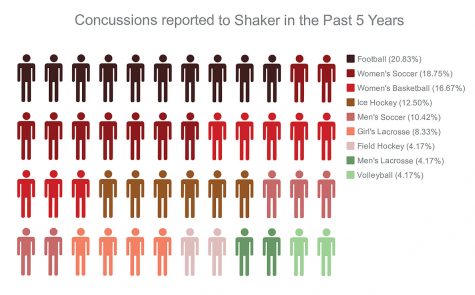

Concern about playing football is rising, but based on concussion data from the high school, parents should also be concerned about daughters who play soccer.

Over the past five years, 48 athletes have brought concussions to the attention of the high school’s athletic trainer, Bob Collins. Football has tallied the most with 10 concussions, but women’s soccer reported nine. This data only represents concussions treated by Collins. Athletes who seek treatment from their doctors are not represented.

A study done by the National Athletic Trainers’ Association found that women were 56 percent more likely than men to sustain a concussion from impact. A collision that concusses two in five men will concuss three in five women.

The study concluded that there are two reasons for this. First, women are more likely to report an injury than men are. Secondly, until women are fully mature, their neck muscles are less developed than men’s. This may account for the nine reported concussions in women’s soccer over the last five years, while men’s soccer players only sustained five.

The Ohio High School Athletic Association added a regulation for concussions in 2013, stating “Any student, while practicing for or competing in an interscholastic contest, who exhibits signs, symptoms or behaviors consistent with having sustained a concussion or head injury (such as loss of consciousness, headache, dizziness, confusion or balance problems) shall be immediately removed from the practice or contest.”

Collins explained how this policy is put into practice at Shaker. “If someone complains of headaches, we have to sit them out. The big thing is, you have to interview them and find out what is going on,” he said.

The urgency of injury prevention and protocol has skyrocketed as technology and medicine advance. Concussions were not recognized as a danger in the NFL until 1994.

Junior Journalism I reporter Juliet Tonkin sustained two serious concussions during her eighth grade year. While playing in a soccer game, Tonkin was hit hard in the head by the ball and was knocked out for about a minute. Her second concussion, which did not occur during a game, came just four months after her first. She said the lingering effects of her first concussion caused her to lose her balance.

“During my eighth-grade year, I wasn’t in school at all, basically,” Tonkin said. “For freshman year, I was on a modified schedule, so I was only taking four classes.”

Tonkin said proper treatment and recovery are crucial.

“After I had such adverse effects from my injury, I just decided that I shouldn’t go back to soccer,” Tonkin said. “It wasn’t worth the risk.”

Tonkin also stressed the importance of preventative measures to avoid severe consequences. In order to be eligible for a sport, incoming freshmen or junior athletes take a required baseline concussion test online. This ImPACT test shows the athlete a series of words and shapes that they must recall from memory. It also tests the athlete’s speed and reactions.

After showing signs of a concussion during a game or practice, an athlete will retake the test. A score lower than the baseline value usually means they have a concussion. But the test is only as useful the baseline value is valid.

Former football Head Coach Jarvis Gibson said, “A lot of times when they take the baseline test for concussions, they just run through and don’t take it seriously.”

In a 2018 story, The Washington Post stated that some athletes purposely score low on baseline concussion tests so that if they become injured or concussed, their subsequent test score will resemble the baseline score — and they will seem fit to continue playing.

“People tend to not understand the consequences of not taking the baseline test seriously. I feel that if they knew some of the things that could happen to them just in high school, maybe that would change,” Tonkin said.

Nationally, similar to Shaker, football players are most prone to concussion injuries.

The Shaker football team did not experience any head injuries this season until senior running back Rasheen Ali was hit during a game against Strongsville Oct. 13.

Ali was running the ball when one of the Strongsville defenders approached. “Someone hit me from the back,” Ali said.

Ali said that the impact of hitting the ground made him feel disoriented and dizzy. Senior quarterback Will Schinabeck walked Ali off the field after he had difficulty discussing the next play.

After the hit, Ali spoke with the athletic trainer at the game and retook the concussion test. He scored lower than his baseline concussion test.

Some players still want to play when they have a concussion because they do not want to let their teammates down.

“I believe the love of the game outweighs the risks. You’re going to get bumps and bruises here and there; it’s what you signed up for. You just have to love the game and do what you do,” senior cornerback Blare Sawyer said.

When athletes on the football team officially become concussed, they required approval from a physician or licensed health care provider before returning to play.

In accordance with OHSAA protocol, coaches must spend the first few days of the season teaching players how to tackle properly — and how to absorb a tackle. Gibson wants to make sure his players are safe on the field, so working on basics is vital. Raider athletes don’t hit each other directly during practice to further prevent injuries. “We work on form tackling and not aiming for the head,” Sawyer said.

“The number one rule is see who you hit,” Gibson said. “The first thing people think to do when someone is coming at them is to put their head down. They think that the helmet is gonna protect them, not realizing that their head will absorb the force.”

This may be why no concussions from rugby were reported to the high schools’ athletic trainer. Rugby requires a different tackling style, in which players lead the impact with their shoulders rather than their heads. Now, college and high school football teams have started to teach the rugby style to prevent injury. According to Gibson, Shaker does not yet teach the rugby tackle.

Although Shaker’s experience with concussions in football has not been drastic, this is not always the case for players across the nation.

On Sept. 30, Dylan Thomas, a 16-year-old linebacker from Pike County High School in Georgia, went into cardiac arrest and died due to a brain injury. Just two days before, Thomas took a direct hit to his head during the third quarter of a game. Scientists concluded that his death was caused by a traumatic brain injury.

Thomas’s injury was extremely rare. According to NBC News, doctors at Grady Memorial Hospital, where Thomas was being treated, explained that his injury required “the perfect amount of pressure on the perfect spot at the perfect angle.”

A more common threat to athletes is Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. This progressive degenerative brain disease was discovered 16 years ago and is similar to senile dementia or Alzheimer’s.

According to the Concussion Foundation, CTE forms when a protein called tau forms clumps that spread, slowly killing brain cells. It is impossible to know how many high school players will develop Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy at this time because the illness is only diagnosed after death.

The earliest symptoms of CTE can begin in one’s early 30s or 40s, after players retire from playing football in either high school, college or the NFL. These symptoms include depression, memory loss and trouble focusing. The symptoms become more severe with age.

The Journal of the American Medical Association published a study of 202 brains of American football players donated after death for research on CTE. Out of these brains, 177 — 87 percent — of them showed evidence of the disease.

More than half of the brains examined for the study came from NFL players. When diving further into the study, doctors found that 99 percent of the NFL specimens had clumps of Tau, indicating the presence of CTE.

Scientists acknowledged that the evidence does not necessarily reflect all NFL or high school football players’ brains. Those who donated their brains to the foundation believed that concussions they sustained affected their long-term health.

While changes in drills and tackling styles may help reduce brain injuries, football — and all contact sports — will remain dangerous, and students will have to consider the risks.

Gibson said, “With a kid who gets concussions, they have to realize, ‘Although I love the sport, I can’t play the sport.’ Health comes first. If health is at risk, never look at the sport again.”

A version of this article appears in print on page 60-65 of Volume 89, Issue I, published Dec. 21, 2018.

Comment using your Facebook, Yahoo, AOL or Hotmail account