Frank Sinatra, A Class Act

Despite the segregated and prejudiced world around him, Sinatra refused to accept the ignorance of his time

Even though I’m a young black man, my mom has a mounting suspicion that I’m an Old White Man in spirit. Some of her theory is supported by my slow, stiff walk, my awkwardly formal diction, and my general grumpiness (especially when I’m tired), but mostly her theory rests on the ungodly amount of Frank Sinatra that I listen to.

Now, my enjoyment of Sinatra’s music isn’t a new development in my life. My most vivid New Year’s memories are of humming along to “New York, New York” after the ball drop, but as a kid, I’d always thought the song was just a throwaway holiday tune like “Jingle Bells,” so I always felt ashamed when looking for it — like, who listens to “Jingle Bells” in their free, non-holiday time? Despite that, I’d always wanted to hear the song again, and laughably forgot that I could always just Google “New York, New York” at any time to find it. Finally, two years ago, my cousin introduced me to Sinatra’s Spotify page, making the man’s music readily available.

Immediately, I was hooked.

I found myself captivated by his vast discography, which conveys the emotional depth of his masculinity. While some songs are slow, lonely ballads about heartbreak, others are explosively triumphant anthems with soaring trumpets that never fail to empower the listener. Besides those extremes, Sinatra covers every emotion in between with his deep, crooning voice and simple lyrics. It’s almost as if Sinatra takes on different personalities based on the song.

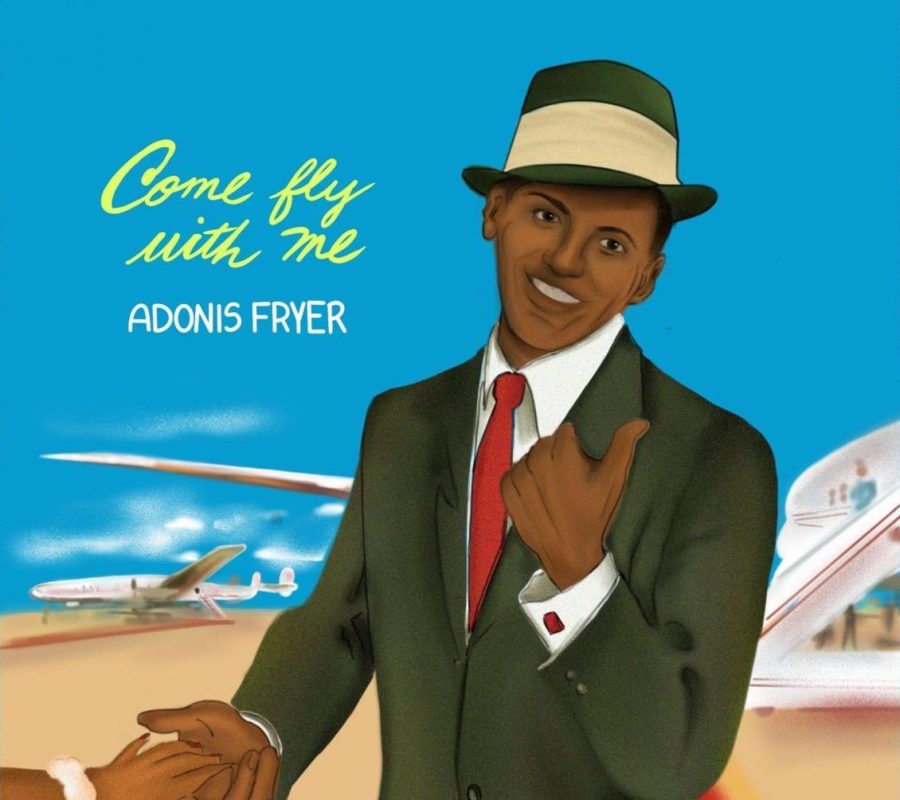

For me, Sinatra’s voice towers over the trivial noises of high-school. Whether I’m listening to “My Way” for inspiration, “I’ve Got the World on A String” for celebration, or “Come Fly With Me” for relaxation, there’s a Sinatra for every occasion.

My enjoyment of Sinatra only hit a snag when I had a late-night thought: “Was Sinatra racist?” After all, surely a rich, white man from early 20th century America would’ve been a despicable racist, right? Despite my admiration for him, I began researching, ready to be disappointed.

It’s not as though I would stop listening to his music altogether, because he’s dead and doesn’t benefit from my consumption, but I could no longer vouch for Sinatra if I discovered toxic ideologies within him.

Thankfully, I found that Sinatra wasn’t just a timeless musician, but also an activist for civil rights.

Sinatra’s distaste for racism was widely documented. He created an award-winning short-film named “The House I Live In” that tackled anti-semitism in 1945; he became instrumental in desegregating Las Vegas casinos; and he advocated integration of the music industry. His band offered equal employment and pay for black musicians, which opened doors in the entertainment industry. Sinatra was a friend to Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, Billie Holliday, Nat King Cole and many other black performers, when much of White America wouldn’t give them their due respect.

But obviously, Sinatra wasn’t a saint. For instance, “The Rat Pack,” Sinatra’s band of performers, sometimes made crude jokes at the expense of Sammy Davis Jr. — a member of the rat pack and famous black performer — during performances, and after Sinatra started supporting Ronald Reagan, his civil rights advocacy decreased. While discussing his flaws, it would also be inappropriate not to mention his womanizing, mob connections, and the other debachurious activities he was involved in throughout his life.

To me, this look into Sinatra’s history strengthened my appreciation of him. While, he wasn’t perfect, I believe his activism outweighed his flaws, and I’m really glad that I didn’t have to delete my playlist. Ultimately it taught me a greater lesson: Absolutely no one is simply a product of the time.

The line of reasoning that excuses historical figures for toxic ideologies, simply because they were common in their era, is nonsense. History has shown that, no matter what makes up someone’s identity, they can stand up against evil systems, whether they are white abolitionists in the underground railroad, or anti-Nazi Germans of World War II.

This idea is incredibly important in our modern America, where indifference to the suffering of people is excused by political motives, and where we’re becoming progressively more polarized along party lines. It’s essential to understand that progress is made by being open to the ideas of others, but remaining resistant to poisonous, hateful ideologies.

In that vein, it’s important to correct our older family members for their problematic stances. I know, it seems difficult, and it’s definitely not always worth destroying Christmas dinner over, but a thoughtful conversation at an appropriate time could do wonders.

In a 1958 Ebony Magazine essay, Sinatra famously said, “You can’t hate and live a wholesome life. Prejudice and good citizenship just don’t go together. Bigotry is un-American.”

Simply put, we can think for ourselves. And we shouldn’t allow ourselves to fall into confining boxes of ideology, no matter what era we’re born into.

Fryer is a member of CORE, the leadership of the Student Group on Race Relations. He is also a drama leader and head script writer for Sankofa. He is a senior at the high school. Guest ‘Rites and Letters to the Editor can be sent to shakeriteserver@gmail.com and the current editor-in-chief, who can be reached at astridkbraun@gmail.com. The Shakerite reserves the right to reject any Guest ‘Rites or Letters to the Editor.

John Elordieta | Oct 24, 2020 at 11:11 pm

“Was Sinatra racist?” After all, surely a rich, white man from early 20th century America would’ve been a despicable racist, right? – Is this your go-to presupposition until people get a chance to prove otherwise?