Don’t Label Me, Except by My Clothes

Price tags and popular brands determine teenagers’ identities

There was a time when childhood revolved around vivid colored pencils and magical books. To marketers, young children were not a primary focus. Businesses have always labeled teens as the “consumers” and “spenders,” and our generation is finally old enough to take our place in this category. But now, instead of selling fluffy pillows and model cars, marketers focus on one thing — clothes.

In high school, to some, what we wear is who we are. Brands frame our identity. It may seem stupid — most teens think what they wear doesn’t define who they really are. Well, sorry to ruin your image of teenagers in America, but status often revolves around clothing, whether you realize it or not.

Before clothing was culture and T-shirts were worshipped, teens would save up for a football or bicycle, or even a college education. Today, people work to spend. Babysitting money and waiters’ tips could easily be going toward a new pair of Converse high tops or graphic sweatshirt to add to their pile of twenty.

A BusinessInsider.com report states that almost 30 percent of teens’ money is spent on clothing, whereas the average wage earning adult spends about 2.7 percent of earnings on clothing. That’s insane.

A survey regarding teen consumer spending habits says clothing is the number one purchased item among teens, and the annual amount of money families spend on apparel amounts to $157.6 billion.

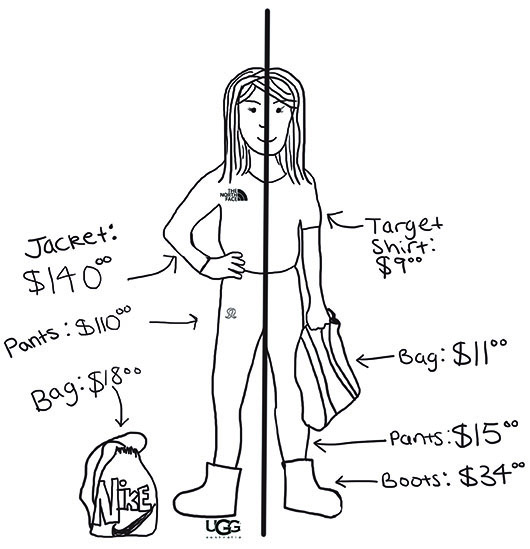

It’s one thing for families and individuals to spend all their money on clothes, but it’s another when the stores they are buying from are extremely expensive. Logically, it doesn’t make sense to buy clothing from a popular brand for more money, when similar looking clothes are available in other stores at a cheaper price.

So why do we buy expensive clothes when we can get them cheaper? Self identity. Certain brands try to create an image of the ideal person that should wear their clothing. For example, J Crew represents the preppy tribe of teens, while Urban Outfitters represents the trendy, bohemian group. Abercrombie reminds you of a skinny and popular 13-year-old girl. Nike fits the stylish yet athletic niche that America embodies. Billabong is all about surf culture. People buy certain brands because what you wear represents who you are, even though it shouldn’t.

Some believe that private school students have different opinions about brands, but an interview with a sophomore from Laurel School shows that she feels just the same as self-aware teens in Shaker. “It makes you feel good about yourself to have things that are popular,” said Elena Householder, a sophomore at Laurel.

An informal poll shows that out of 20 students, 16 chose Urban Outfitters and lululemon as their favorite places to shop. Asked what teen stores are most expensive, 19 students listed these same two stores among others.

Shoe culture is a different story. Shoes are a staple in American culture. Somehow, an irrelevant size 8 sneaker can determine social status. Nike remains the top clothing brand for all income levels. Top footwear brands for upper-income teens are ranked; Nike, Vans, Converse, Sperry Top-Sider, Timberlands and Steve Madden. Wearing designer clothing or shoes aligns you with an elite group: those who can afford it. Teenagers have grown to be able to tell cheap clothing from expensive clothing just by glancing at garments. When you wear a Vineyard Vines shirt, you appear wealthier and of higher social status than others. And who doesn’t want others to be insanely jealous of your clothes?

“I wish I could say, ‘Brands are pointless,’ and ‘I’m not going to let a label determine my status,’ but I can’t. They do,” Householder said. Junior Shaniya Weaver explains that there’s a difference among races in terms of clothing. “Black culture is all about Jordans and what type of Nike’s guys wear, but I feel like white culture is focused less on shoes and more on spending money on preppy clothing,” she said.

There is also the pop-culture side of things. Celebrities influence their fans’ wardrobe just by walking down the street.

“If an artist you like is wearing a certain brand, you feel this obligation to be like them,” said Weaver.

The Economist published an article in which the author stated, “Designers of fancy apparel would like their customers to believe that wearing their creations lends an air of wealth, sophistication and high status. And it does—but not, perhaps, for the reason those designers might like to believe, namely their inherent creative genius. A new piece of research confirms that it is not the design itself that counts, but the label.” Brand name boosts status, and while teenagers so often wish that labels didn’t define them, unfortunately they’re wrong.