The Asking Olympics: Why Can’t Girls Go For the Gold More Often?

Examining the gender roles attached to school dances

The Olympic games are a cutthroat event. Like people all over the world, I’ve come home each night the past two weeks glued to the TV, watching cliffhangers unfold before my eyes. Athletes are given one shot to leave it all out on the rink, the court, the slopes — with sometimes just seconds to make the difference between glory and anonymity.

Combine that same competitive intensity with teenage girls, social media and a school dance, and you’ve got the Asking Olympics.

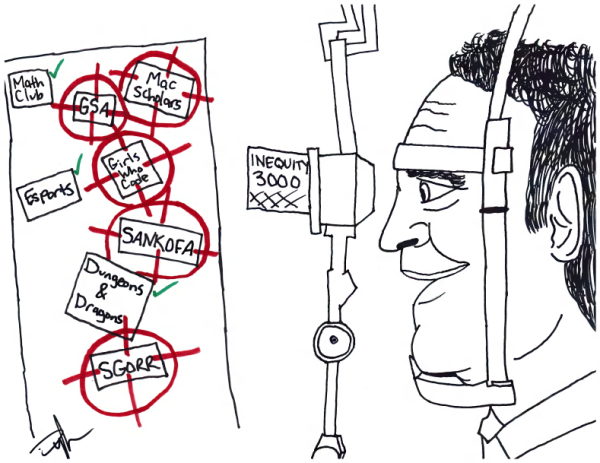

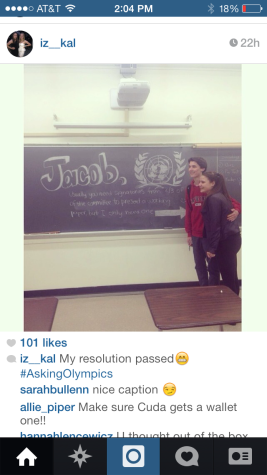

Developed by Student Council, the Asking Olympics are a plan to encourage girls to ask guys to the dance with the promise of free tickets for the most public and creative proposals. To date, the contest seems to be working quite well, with girls posting all manner of imaginative requests. So far, more than a week prior to the March 1 Olympic Ball dance, girls have not been holding back, with proposals involving lost and found posters, a feigned arrest and even a full-fledged marauder’s map Harry Potter scavenger hunt.

Despite all this success, however, the Asking Olympics and the whole concept of a girls-ask-guys dance are part of a trend that just may be on its way out. In a world where not only same-sex couples, but gender equality as a whole are finally becoming one of society’s higher priorities, doesn’t it seem a bit outdated to have dances where we must specify who may ask whom?

Senior Zach Steckel acknowledged the deeper significance of having every dance dictated by which gender assumes the stress of choosing a date. “I feel like there’s definitely a lot of pressure on guys to always be the one to initiate relationships or ask girls to dances and such. I’m definitely OK with a dance when the responsibility is taken off of the guys for a change, but I would be way more okay if the social norm got entirely away from the ‘one gender asks another’ thing,” Steckel said. “Yes, it’s nice to have a dance when the girls ask the guys, but that just emphasizes that the guys have to ask the girls for all of the other dances. I wish that it went both ways all of the time, you know?”

Steckel echoes the sentiment of a generation that may be finally ready to cast off gender roles that have been in place for far too long. Shaker’s need for just one dance set aside where girls are allowed to be in control is indicative of our society’s expectations of men and women as a whole. Will it ever be a majority opinion that it’s alright for a girl to take initiative outside the confines of a Sadie Hawkins dance?

Junior Narayan Sundararajan addressed the social constructs that accompany dance proposals. “From what I’ve seen, it seems to me that whenever a girl asks a guy to a dance that’s not MORP there’s always gossip about whether the guy who was asked was ‘man enough’ or what the girl was thinking when she made that decision,” Sundararajan said. “Basically, I think that once that stigma is removed there may be a shift towards more girls asking guys to any school dance.”

However, removing a social stigma is easier said than done. Sundararajan also admitted the difficulty of changing the way a culture approaches relationships. “I think that our society has a deep rooted sentiment that when it comes to something like romance, guys have to do the work — and I think that that’s something that’s not really going to change, at least in the foreseeable future,” Sundararajan said.

All in all, Sadie Hawkins (sometimes called MORP for prom backwards) dances are a positive thing, because they give girls the chance to take matters into their own hands. What’s troubling about them is the fact that they need to exist at all. If a girl, or anyone for that matter, wants to ask someone to a dance — or even later in life, propose a marriage — can’t he or she be able to go ahead and do so without worrying about how it will be perceived?

Sundararajan finds the concept of being asked to a dance refreshing. “In terms of romance, gender roles have always been skewed in favor of the male — we’re supposed to front the bill when it comes to a date, we’re the ones who are usually supposed to ask the girl in a proposal, and, of course, we’re usually expected to ask a girl to a dance. I think that it is nice to an extent; it ties in with the whole notion of having a male be chivalrous, and encourages them to actually be forthright and more kind to girls,” Sundararajan said.

Despite the idea of chivalry, Sundararajan wouldn’t mind a girl going ahead and asking him herself. “Asking a girl to a dance is probably one of the most stressful things you ever do in high school; you have to make the way you ask the girl look nice, you have to accept that the girl may say no, and you have to actually build up that courage when doing so. I enjoy having at least one dance where we’re able to have the chance to sit back and let the stress and planning fall on the girl. I’ve heard from a lot of guys that it feels nice not to have to think of ideas for asking someone to the dance. I’ve heard from some guys that they get stressed out and feel awkward if a girl doesn’t ask them, but I personally think that that opinion is a minority one and that for the most part guys are more ‘chill’ when it comes to a dance such as MORP.”

Boys aren’t the only ones open to the idea of girls taking the lead more often. Sophomore Abby Connell hopes to see the Sadie Hawkins tradition continue beyond just one dance. “I don’t like the expectation that the guys should be the ones to propose,” Connell said. “ I’m all for chivalry and being a gentleman but I think that we’re at a point where women should take initiative too! And so we shouldn’t send the message that asking to dances/proposing is the guy’s job.”

Senior Monica Nemeth summed it up perhaps best of all. “Well, I suppose I don’t stand by the traditional definition of chivalry. I always offer to pay because I never expect or assume that that is the guy’s responsibility,” Nemeth said. “I see chivalry as simply as acting politely or holding the door for someone. So by my own standards I could consider myself chivalrous.”

According to Nemeth, chivalry is not dead — it’s just becoming universal. It makes complete sense. Though it’d be naive to hope that gender norms have been re-invented by the time the next Olympics rolls around, as seen by opinions of students like Steckel, Sundararajan, Connell and Nemeth, we may be off to a good start. Perhaps it’s realistic to hope that some generation of Shaker students in my lifetime will enjoy a dance — and a culture — where gender roles are no longer barring girls from being able to take the lead.