Shaker Heights Middle School staff face IB implementation, a new retention policy and a building full of 12- and 13-year-olds as they attempt to improve both the school’s state report card rating and community reputation.

The ‘Difficult Years’

Looking at what shapes Shaker's lowest-ranked school

May 3, 2014

The Great Mace Incident of 2011 occurred during the middle of the school day, in the middle of the school, at Shaker Heights Middle School.

A female seventh grader brought mace spray to school to retaliate against another girl for an out-of-school disagreement. In a hallway near the cafeteria, she sprayed the girl, she sprayed bystanders and she sprayed teachers who tried to intervene. Ambulances arrived at the Shaker Boulevard campus, and the incident has immortalized itself in Shaker memory.

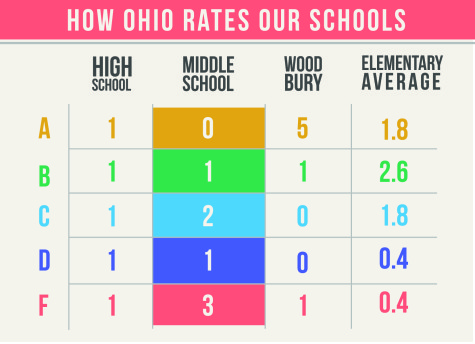

Such extreme events happen rarely at SHMS, but they contribute to the middle school’s poor reputation. The middle school has also performed the worst of all Shaker buildings on the state report card since at least 2009. It had eight infractions resulting in suspensions or expulsions in the first 17 weeks of school this year, more than any other building. According to a district survery, just 55 percent of middle school students find their courses challenging.

Of the Shaker Heights City School District’s eight schools, the middle school has the worst reputation. Over the past quarter, The Shakerite’s Campus and City section investigated why that’s the case, and what’s being done to fix it.

State Report Card

One reason for the middle school’s negative reputation is the the Ohio Department of Education’s annual report card. The most recent report card, released in August 2013, gave SHMS an F for three of its value-added scores: overall, disabled and the lowest 20 percent of students. Value-added scores measure students’ improvement during the school year, based on tests given at the beginning and end of that year. Besides the middle school’s three F’s, the most any other Shaker school earned was one.

Two C’s rounded out the middle school’s rating, one for the annual measurable objective, also known as gap closing, which takes into account students’ reading and math scores and graduation rate, and the other for its gifted value-added score. The middle school met three of its five standards, earning a 60 percent and D in that category. All other Shaker schools met 100 percent of standards.

Other local school districts lacked the same gaps in ratings between their middle schools and their other buildings. Orange City’s Ballard Brady Middle School had higher ratings than its elementary school, while Chagrin Falls’ middle school and elementary school were ranked almost identically. Of the Cleveland Heights-University Heights district’s three middle schools — Roxboro, Frank L. Wiley and Monticello — Monticello was tied with an elementary school for the district’s worst rankings, but Wiley was ranked highest.

Superintendent Gregory C. Hutchings, Jr. said the state places too much emphasis on its end-of-year assessments. “We’re looking at one test date. So you have one bad day. Anything could have happened that day. That one day now determines how effective your year was,” Hutchings said.

He explained the school shouldn’t be judged on one test, just like a student shouldn’t be. “They don’t look at all the factors that come into play: maybe you made it to school every single day, maybe you did your homework every single day, maybe you did have a relationship with your teacher, maybe you did have a job,” Hutchings said. “None of those things are a part of the rating.”

“It’s an important factor — don’t get me wrong — but it’s just one piece to this puzzle,” he said.

Middle School Principal Danny Young agreed. “I just think it’s one snapshot. It doesn’t give the full school experience,” he said. “We’re going to tackle it and work hard to close the achievement gap and improve our status.”

Transition

Young thinks his school performed poorly on the report card in part because of the “tough transition” between Woodbury Elementary School and the middle school. At Woodbury, “you’re escorted and walked to every class” and there are five transitions.

“Then you’re sent here, and now, boom! Nine classes, you’re on your own, you have to get a feel for nine different teachers’ expectations and styles,” Young said.

“Some kids hit the ground running because they’re organized, they’re motivated, they have a system in place, they know how to go from class to class and write down their assignments; they know how to advocate for themselves. And we have some students that need a bit more support with that.”

Seventh grader Esmé Alexander-Jaffe agrees that middle school students face challenges because “it’s a lot different from Woodbury and elementary school,” she said. “It’s a lot harder.”

Shaker parent Chris Ramsay, whose three children attended the middle school, also saw difficulties in the transition. “There’s this huge transition for the kids,” he said. “For a lot, homework is an issue, focus is an issue, and the social stuff becomes more and more a part of their daily lives.”

According to “Measuring What Matters,” the district’s profile of its schools, 55 percent of middle school students say their classes are challenging. That number is 70 percent for Woodbury and 78 percent for the high school.

Young pointed out that while Woodbury has 57-minute classes and the high school has 50-minute classes, the middle school only has 39-minute classes. “I think that’s a big goal as far as we need to improve on instructional time,” he said.

“Every transitional year, you see a little dip [in test scores], and you see it come back up that next year. I think that’s across districts. I think that’s not a Shaker thing, I think that’s a school-wide, school district thing,” Young said. “We’re having more transitional programs to sort of ease the anxiety of kids as they move building to building, and I know that’s a big goal and initiative for the future.”

Hutchings agreed, saying, “One area that I had a concern about is the transition from Woodbury to the middle school and the transition from the middle school to the high school. I think that we need more of a robust transition program or process, because I don’t know if we’re having enough collaboration with our teachers.”

Consolidating schools would lessen the number of difficult transitions. However, “It’s nothing that’s on the table today,” Hutchings said. “But I think it is something that we can definitely have discussions about for the future because from what I’ve heard, a lot of the parents have a concern about going from the K-4 to a 5-6 then to a 7-8 then to a 9-12, and they feel that the moment the school really gets to know their child at Woodbury and the middle school, then it’s time to transition to a new building. They have to start all over.”

Hutchings said combining buildings is not under discussion for the five-year strategic plan the district is developing. However, Young said, “I think, in the near future, I could see Shaker moving towards fewer transitions.”

Developmental Age

Another reason for the subpar state report card, according to Hutchings and Young, is that the middle school comprises 12- and 13-year-olds who are maturing.

“You’re trying to figure out where you fit in, as far as, you’re trying to figure out which group you’ll kind of grow close to. ‘Who are my friends? What’s my niche going to be?’ Your bodies are changing. Everything is just kind of going haywire internally,” Young said.

Hutchings agreed. “I think that the developmental phase of the middle school is a very important factor that we have to put into consideration with everything,” he said.

At middle school students’ ages, social media gains importance as well. “There’s all this bizz-buzz that happens at that age online and then gets to school,” Ramsay said. “So there’s that complexity that’s in the mix now too, which makes it even tougher.”

Hutchings said SHMS is “just like any other middle school . . . Through my experiences, in regards to what happens in the middle school here, it’s what happens across the country. Kids are at the same developmental age in their lives. You still have the same issues with students who don’t like other students and cliques — it’s the same type of issues. There’s nothing that I believe, at our middle school, that’s so abnormal from any other typical middle school.”

Hutchings said that in every district he’s worked in, “the middle school has always been the most challenging. And I think a lot of that is because of that developmental piece. I really do.” He said middle school is “always the focus, wherever you go.”

However, students’ developmental ages are a hard task to tackle. “I don’t know if there’s a pill we can swallow to fix it,” said Hutchings, who does, however, think the district can be more “proactive” in dealing with it. He would like faculty to hold discussions with students to help them understand “why some of these things are happening,” he said. “This is normal to be trying to figure out who you are. This is normal to be on an emotional rollercoaster.”

Behavior

Students’ developmental ages play a role in behavior at the middle school. “Research says, scientifically, you begin to have emotional changes, which causes you to have an attitude one day, and the next day you’re fine,” Hutchings said.

However, other sources of bad behavior exist at SHMS as well. Ramsay believes that teachers currently lack the necessary tools to handle bad behavior, and that some students take advantage of that.

Ramsay mentioned a field trip he attended at a movie theater with one of his children’s classes. Teachers “had to separate all the kids . . . so they didn’t poke and prod each other. But there was seat jumping like an Olympic event, there were people on their phones and throwing food.”

Ramsay said he told his concerns about the students’ behavior to a teacher, who responded, “ ‘Oh, this is pretty good.’ ”

Young said students often become “squirrelly” on field trips. He said teachers “most definitely care about behavior.”

In an attempt to improve behavior at the middle school, Hutchings hired a Response to Intervention specialist before this school year. He said he brought RTI specialists to many districts he worked in before as well.

In an email interview, the RTI specialist, Robert McMahon, said he has “many of the same duties and responsibilities as the two assistant principals. I would estimate that 65-75 percent of a typical day for me involves handling student discipline and student affair issues in an effort to assist and support the assistant principals.”

According to data provided by Young, as of April 16 the middle school had a total of 143 suspensions and one expulsion this school year. All of last school year there were 147 suspensions and three expulsions. In the 2011-12 school year they suspended 214 students and expelled two.

“Our goal is to keep kids in class, because if they’re not in class, they’re not learning, therefore the odds of them doing well on the tests kind of decreases. So we’re making a concerted effort, when at all possible, to keep kids in class,” Young said.

Eighth grade English department chairman Ronald Grosel said testing is a concern when addressing behavior.

“They don’t want to suspend or expel kids because of the testing,” he said. If administrators do suspend or expel a student, the student “misses out on all the teaching and then they’re not going to do well on the test.” Grosel added that he thinks there’s a good balance. “If a kid needs to be out of here, they’re going to be out of here,” he said.

Young said it’s important to ensure “that we provide [disciplined] kids with the work. So the teachers will provide the work for the kids while they’re out on suspension or in-school [detention].”

Grosel said McMahon has helped. “For example, he’s put together a list of people who are chronically late to class. If they’re late, it goes directly to him and he deals with them immediately.” Grosel said the list includes about 15 students. “Those kids are getting to class.”

“Having more people is definitely better. More security guards would be even better,” Grosel said. SHMS currently has three security guards. “The more people that can take care of what’s going on, the better.”

Grosel has worked at SHMS for seven years. “To be honest, since I’ve been here there hasn’t been a lot of fighting. There’s some hallway issues,” he said.

Alexander-Jaffe disagreed. In March 2013, reflecting on her past six months of seventh grade, she said fights occurred “almost every week.”

“In Woodbury, if two kids got into a fight, it would be broken up immediately,” she said, adding that is not the case at SHMS.

Alexander-Jaffe suggested that teachers pay closer attention to students who get into fights. “It’s usually the same kids that get into fights,” she said. “I feel like [teachers] shouldn’t be all over them, but they should watch them.”

Young said McMahon gave the leaders of each seventh and eighth grade team a list of “kids most likely not to score ‘proficient,’ ” with charts of ‘Best Practices’ in math, English and behavior management. “We asked [the team leaders] to go back to their teams during their team-leader meetings to talk about what strategy can they implement with those kids and track during a six-week period and see if they make some gains and some differences with kids. So we meet every month and talk about, ‘Is it working? Is it not working? What should we do differently?’”

“Behavior with middle school aged children is often a challenge, and my goal is to counsel students to make good choices when it comes to their behavior,” McMahon said. “Discipline and consequences should be more than punitive in nature. I believe discipline must include a reflective element that encourages students to think about what they did, take responsibility for their actions, and learn a lesson so the misbehavior is not repeated.”

Young said McMahon has “done a phenomenal job with supporting kids as far as responding to their learning needs.”

Both Young and Grosel said they would be in favor of the district hiring another RTI specialist for the middle school. Hutchings said he would have to analyze data at the end of the year to see if that would be worthwhile.

Social Promotion

Hutchings announced he was ending social promotion at the middle school last August. The district’s retention policy allowed students to progress to the next grade even if they failed one or more of their classes.

Social promotion was never an official policy. The Board of Education amended its previous retention policy, written in 1987, in April. “The decision to promote, retain or accelerate will be made by the building principal following consultation with the teacher/s and the parent/guardian,” the previous policy said. “The parent/guardian has the right to appeal the recommendation to the Superintendent’s designee.”

Hutchings said he thought the general language of this board policy allowed social promotion to take place. Asked why the board waited more than six months to change the official policy, Hutchings said the revised policy incorporates “some of the state mandates that have changed, we had to adopt some of the state language into that policy.”

One middle school teacher provided The Shakerite with a document summarizing the school’s Feb. 10 “Building Leadership Meeting.” “Retention discussed w/ upper management. Draft of process planned to be in place by end of 4th quarter,” the document stated.

Grosel, who was at the meeting as the eighth grade English department chairman, said that was the first time teachers saw anything about the new retention policy in writing. “Early on there wasn’t quite a plan. Say first quarter. So a parent would call in, and a counselor wouldn’t know what the actual plan was. It was just kind of, ‘This is the idea, this is what we want to do, but nothing set in stone,’ ” he said.

However, Grosel said teachers are not doing much differently now that social promotion is over.

“They’re doing their thing: making phone calls, having conferences, giving kids missing assignments. But the difference is now when they come in, there’s an urgency for them. ‘Oh, we might not go to the high school, so we’re actually going to do the work, we’re going to come in to conferences,’ ” Grosel said.

“We want them ready for the high school. That’s the bottom line. If they’re not ready, they’re not going,” Grosel said.

Young said he doesn’t think teachers feel pressure to pass students so they won’t be retained. “I think they feel validated. I think they feel like, ‘Man, my subject matter really counts, and now the kids kind of have to meet me halfway and really do the work,’ ” he said.

“Pretty much it was up to parents previously” whether their students were retained, Young said. “We might make a few recommendations [to retain kids], but then a parent could say, ‘No, that’s OK, I don’t want that,’ and they moved on.”

The revised policy does not mention parents. “The promotion of each student is determined individually. The decision to promote or retain a student is made on the basis of the following factors. The teacher takes into consideration: reading skill, mental ability, age, physical maturity, emotional and social development, social issues, home conditions and grade average,” it states.

“Now we have more specifics as to how a student can be promoted, how a student cannot be promoted. Now we have more specifics so that we’re being more consistent with our practices, and people have a better understanding as to what our expectations are for promotion and retention,” Hutchings said.

Grosel supports the move because he thinks socially-promoted students haven’t been prepared for the high school. In 2013, 74 freshmen were held back for failing one or more classes, about 15 percent of the grade. “I think there are too many students who don’t take their education seriously, and in the past, there hadn’t been any repercussions; they would always go to the high school. So we could tell them you’re not going to be able to do this at the high school, but they wouldn’t listen,” he said.

Ramsay agreed. While his children attended the middle school, “there was a sense that, you know, sometimes [students] figure out, ‘Well, my grades really don’t count, and I’m going to get put up to the next grade no matter what.’ There was no real threat of, ‘They’ll force us to repeat,’ or something like that,” he said.

District Communications Director Peggy Caldwell said she was unaware of any data the district keeps on the number of students socially promoted at the middle school.

Mark Storz is a professor in John Carroll University’s education department, the associate dean for graduate studies in JCU’s College of Arts and Sciences and a former middle school principal. He opposes social promotion. “When we socially promote kids, we really give them a false sense that they’ve mastered the knowledge and the skills that they need for later success,” he said. “That’s going to affect their performance in high school and, quite frankly, it’s going to affect their performance in college.”

Social promotion also disadvantages teachers, Storz said. “If I’m in a classroom with eighth graders, and I’ve got eighth graders in there who are doing eighth-grade work, but then I also have these folks that have been socially promoted without the knowledge and the skills to do eighth-grade work, and I’ve got both of these groups of children in my classroom, it makes my teaching really hard because of the different needs that these kids are going to have,” he said.

However, Storz said exceptions exist. “There are some students who, for whatever reason, need to be socially promoted, and I think that kind of stuff happens on a case by case basis, and the principal, the teachers, the guidance counselors can make those kinds of decisions,” he said.

Hutchings agrees and, accordingly, has not ended social promotion entirely. “Social promotion is appropriate for certain situations,” he said. He gave the example of a 15-year-old who transferred into Shaker’s seventh grade this year from another school district. The school is exercising “alternative ways” to raise that student up to grade level as quickly as possible, including online learning and a tutor, and the student will likely be socially promoted at the end of the year to a grade more appropriate for his age. “He may not ever catch up, but maybe he’ll only be one year behind, versus two,” Hutchings said.

Seventh grade social studies teacher Michael Sears said student age is a concern. “The challenge becomes, with this age group, do we really want a 16-year-old driving to the seventh grade?” he said. “That may be an extreme example, but there are social and emotional issues about retaining kids at this age.”

Hutchings said state law recommends that schools not retain students more than twice during elementary school and more than once during middle school, “so the law really prohibits you from retaining kids over and over . . . Anytime a student is being retained multiple times, there’s another issue,” he said. “So I think it’s our responsibility as a school district, as educators, to try to identify what those barriers are.”

However, most students failing classes will not be granted exceptions. As such, the district has instituted new measures to keep students on track this year.

Hutchings explained that SHMS alerted families of students who had failing grades in the first four and a half weeks of school, asking them to encourage students to attend tutoring and conferences. At nine weeks, the school contacted struggling students’ parents again, and had guidance counselors talk to the students. After the second quarter’s progress report was sent home, SHMS contacted students’ families again and Hutchings held an assembly for those students at school. Assistant Superintendent of Secondary Education Marla Robinson sent out a plan about “how we’re trying to serve or meet [students’] needs so they can finish school and pass” at the end of first semester.

Young said that as of April 8, 132 students are at risk of being retained. “That’s not bad out of 860 kids,” he said. “Do I want any number? No, but we’ve got to be realistic. Some kids aren’t going to do their homework.” He said he expects fewer than 50 students will be retained at the end of the school year, and that in five years, “probably none” will be retained.

“That’s just my gut,” Young said. “Can I guarantee that? I can’t guarantee anything.”

“What I think is going to happen after a year or two of this, I think the message is going to go out, and it’s going to change the perception that the middle school really does count,” Young said.

Grosel agreed. “I think we’re starting to see it a little bit, but I still think people don’t quite believe it,” he said. He said he thinks one round of students will have to be retained before everyone believes it. “Next year I think the word will get out, ‘They’re not kidding, they’re going to hold you back,’ ” he said.

IB MYP

SHMS is in the process of implementing the International Baccalaureate Middle Years Programme, which comprises grades five through 10. The district has already been certified for IB Diploma Programme, grades 11 and 12, and Primary Years Programme, grades kindergarten through fourth. The district will apply for MYP approval in October and will hear back from IB in spring 2015.

In a September interview, Hutchings said the district was one semester behind in the MYP certification process.

“I personally believe that IB is very well aligned with exemplary middle school practice,” said JCU’s Storz, who has documented the Cleveland Heights-University Heights school district’s IB implementation. “IB really provides opportunities for students to be engaged in their learning, and when students are engaged, they’re actively participating, and when they’re actively participating, there is the potential for much higher levels of learning and thinking and developing many of the 21st-century skills that we talk a lot about in our field.”

Alexander-Jaffe said she and most of her classmates find interactive learning more “fun” and effective. However, she does not think IB is accomplishing that.

So far, she thinks IB feels forced, rather than well-integrated. “I feel a lot of people find it annoying,” she said. She said SHMS is “trying to make everything about IB,” but “I feel like if someone asked someone to describe IB, they wouldn’t know how.”

Grosel thinks students are “a little leary of it, but just because it’s challenging, and they know it’s work and it’s not easy.”

Storz said that early on in IB implementation, “a student could see it as being forced, when in reality, let’s stick with it for a few years, and as it becomes more fully implemented over the course of one, two or three years, it’ll make more sense. I know that’s the case in Cleveland Heights,” which is in its second year of implementation. SHMS has been implementing IB MYP for four and a half years.

Dexter Lindsey, the middle school’s MYP coordinator, viewed students’ dissatisfaction with IB differently. “Our students are adolescents,” he wrote in an email in February. “Developmentally, it would be uncharacteristic for them to share with us that they like MYP.”

Storz understands Lindsey’s opinion, stating that “at the time I was principal [of a middle school], I probably would’ve said something very similar to what that teacher said. Sometimes it does seem like young adolescents have difficulty with change.”

However, he said all people find dealing with change difficult, not just adolescents: “I think that’s true of a lot of us across the lifespan . . . I’m guessing that there are a lot of students who, as time goes by, are really going to appreciate the IB because of the way in which it’s meant to engage them,” he said.

“With any big change, it takes time to implement it fully and sometimes, along the way, it doesn’t always look like it makes sense,” Storz said. “But if we go through the process of change, at the end of that process, it works.”

Making IB work at the middle school is Hutchings’ goal. He hopes integrating IB will raise instructional quality there. “I think that if we can have good instructional practices in our classrooms, if we can get our authorization for IB MYP . . . if we can begin discussions around some non-negotiables as to what needs to happen in all classes at the middle school regardless of what your teacher’s teaching or who you are, that we’re going to get the biggest bang for our buck,” he said.

Young also believes IB will improve classroom instruction.

Grosel supports IB because it makes teaching more uniform. “In the past too many people were doing their own thing. While that’s good for maybe that group of students, it’s not good for everyone throughout the whole school,” he said.

Storz believes IB’s emphasis on interactive learning and its “interdisciplinary nature” between units of study make it a worthwhile curriculum. However, he thinks such components “are also part of good middle school practice.” He did not know enough about SHMS to comment on its faculty or teaching methods, but said that rather than replacing curricula, in a good middle school, IB “just reinforces what good middle school practice is.”

The only distinction between MYP and good middle school practice is “global-mindedness,” Storz said. “The inclusion of languages, the inclusion of the study of culture across the disciplines, I think that’s a distinguishing piece that’s important for a lot of American students. We tend to be pretty isolated compared to other countries in the world.”

“If teachers really engage the IB philosophy, and if they really work to implement the type of teaching that IB encourages, then I think the kids will begin to see really positive changes,” Storz said. He believes that providing teachers with professional development opportunities such as attending conferences and visiting other IB schools is necessary to implement IB effectively, because IB is also new to teachers, not just students. He said professional development helps teachers “understand and implement a change.”

Storz believes IB will benefit SHMS in the end. “I wouldn’t want to suggest that IB is going to make things better because that’s saying things aren’t good, and I’m not in a position to say that,” he said. “But I certainly think IB has the potential to enhance what’s going on in the middle school.”

Substitutes

According to Grosel, the middle school’s substitute teachers are “awful.”

“For me personally, I try to never be absent. And I’m not, except when I have to do professional development,” he said. “They’re asking us to do more and more [for IB, RTI and Common Core]. It’s kind of a given that when you’re gone, nothing gets done.”

Grosel said teachers worry about their students doing worse on end-of-year assessments, which are part of their teacher evaluations. “The more you’re out, the less your kids know, the worse they do on the test, the more it affects you,” he said.

Young said he hears concerns about substitutes from teachers frequently. “Every year we’re going to try to decrease the number of times teachers are out of the classroom” for professional development, he said. “They’re not out just twiddling their thumbs. Every time they’re out, there’s a specific, targeted reason.”

Grosel agreed: “Based on what’s going on [with IB, RTI and Common Core], it’s necessary.”

Grosel and Young both said that the district’s best substitutes are typically hired as full-time teachers.

Because they don’t want to miss class, Grosel said the English department is devoting the first two weeks of summer to tailoring its curriculum to the PARCC exam, which tests achievement of Common Core standards. “I think using summertime is a good option,” he said, but added that it’s difficult to get every member of a department to agree to forgo vacation time.

Instruction

Hutchings said he goes to SHMS around twice a month and frequently visits classes. “In some of our classes, I’m not going to say all, particularly some of our CP classes at the middle school, I’m seeing a lot of low-level work happening in the classroom,” he said. “I think it’s important for us to provide high-level, higher thinking, critical thinking and analytical skills in classes regardless of what level it is. And that’s one thing that I’m not seeing consistently throughout the building, so that’s a concern.”

However, Hutchings said he sees this “in different pockets throughout Shaker schools,” not just in the middle school. He said he thinks the Ohio Teacher Evaluation System’s accountability system will allow him “to address that.”

“I also think that as we move forward into the next five years, with our five-year strategic plan, because we have a focus on instruction and establishing protocols on how to teach our kids, that we’re going to see some commonalities in regards to teaching practices throughout Shaker, throughout the entire district, and we won’t just see it in pockets,” he said.

“I see a lot of good instruction. I see a bit of bad instruction, too. I would like to consistently see good instruction no matter what class I go in, no matter what building I’m in, no matter what time of the day it is.”

Unlike middle school teachers, Hutchings would like to “provide teachers with more professional learning on how to reach all students in classes . . . [and] how to use data to make instructional decisions in the classroom.”

Hutchings said he considers professional development key to improving report card grades at SHMS. He said his 4-year-old son’s generation learns in a very different way than his generation did because of changes in technology. “We have to provide our teachers with the skills to meet the needs of that next generation,” Hutchings said. “What is it that we have to do to get you all a better conceptual understanding of the material? That is going to be our biggest shift.”

Wrap-around services

Social studies teacher Michael Sears said teachers need to have “higher expectations for the kids who are struggling. We have to expect that they’re going to be able to focus in class for 30 minutes or 40 minutes and expect that they’re going to try their best, and they’re going to do some homework, and that there are going to be programs in place to help them so that they’re working somewhere between four and six [p.m.]. Something has to be happening between four and six, because when you get to middle school, if there’s nothing happening outside the classroom, you’re just falling further and further behind.

“I think we sometimes overlook the social-emotional needs of kids in middle school, and if we could improve those needs, the academics would improve,” Sears said. “We just have to get kids more involved who aren’t in activities or don’t have a sport or a club, get them feeling connected.”

Young said SHMS is trying to “implement more wrap-around services, more support programs” to help struggling students.

Young gave the example of a new program in which six parents “volunteer to come in during the lunch [and] study halls, to come in and meet with tardy kids who, we’ve told them, that they probably could work with around organization, around getting their planner filled out, making sure they have a plan to go to conferences that we can see, just so parents can be that facilitator of how to navigate the middle school right now.”

Hutchings cited an initiative in which an employee of Bellefaire, a non-profit that provides children with a “variety of behavioral health, substance abuse, education and prevention services,” is based full-time at the high school and middle school. That way students have access “in house, whereas in the past, we would refer students to their [Bellefaire’s] center.”

Young said the employee based at SHMS “can help with the social and emotional needs of the kids to make sure they have some support with their social, emotional help that might translate into the classroom to help them.”

Young said the middle school’s guidance counselors and administrators each have “10 kids that we take, and we just check in to make sure that, you know, they have what they need, and if there are some barriers that are up that need to be broken down, we’ll do what we can to try to break them to, to help them be successful.”

Principal

The district announced in March that Young will replace long-time Shaker administrator Randall Yates as principal of Woodbury next year.

Young’s move to Woodbury was part of a larger administrative “reorganization and succession plan.” The district has hired a national search firm to find a new middle school principal, assistant superintendent of business and operations, curriculum director and director of technology and media services.

Hutchings said they hired the firm because “these are four very important areas.” He said all four jobs focus on areas that the community expressed concern with in the leadership profile for his job. The same firm wrote this profile when the district sought a new superintendent last year.

“We want to get it right so we’re not in the position of having to hire somebody [new] three to four years from now,” he said. “We can’t have people coming and going every couple of years. That would be a disaster.”

Asked why he wouldn’t hire a new principal at Woodbury and keep Young at SHMS, Hutchings said, “We grappled with posting the position at Woodbury. We wanted to try to provide them with some stability in regards to having an individual that understands Shaker schools, that understands the city, that understands what we’re striving for in regards to our fifth and sixth graders, because they’re going to the middle school, so we need someone to understand what we’re trying to produce.”

Hutchings stressed that moving Young to Woodbury was not a pre-determined plan. He said Young’s name came up when Hutchings’ cabinet discussed the vacancy, and they decided that Young’s seven years as a third-grade teacher at Mercer Elementary School made him a good fit.

Hutchings added that moving Young to Woodbury was not an indictment of his middle school performance. “If he was not good enough for the middle school, if he didn’t have the skill set, the knowledge, the ability to be an instructional leader, he wouldn’t work in Shaker Heights. I don’t believe in moving someone who’s ineffective to another building. I believe in moving them out of Shaker City Schools. If you’re not good enough for one group of kids, you’re not good enough for the other group of kids.”

Hutchings said that if Yates had not declared his retirement, Young would have remained at SHMS. “This opportunity opened up. We took advantage of it,” he said.

However, Hutchings did not seem to mind that the move creates a vacancy at SHMS. “If we have a perfect candidate that can take Woodbury where we need to go, and will give us the vacancy at the middle school to accomplish what we need there, it’s a win-win. He’s a perfect fit for what we need in this building, then we go find who we need to run the middle school,” Hutchings said.

Hutchings said the middle school needs someone “who is going to be able to put all these different pieces together.” He said the pieces include Common Core, IB MYP, negative perception about SHMS and issues associated with developmental age. “It takes a special person with a special skill set to be able to do that.”

“Mr. Young was the right person for the time that Mr. Young was there,” he said, adding that the decision had nothing to do with state report card grades. “That was not a part of the decision.”

“It wasn’t really about the middle school for this decision,” Hutchings said. “It was about what we needed at Woodbury.”

Young said he was happy to accept the cabinet’s request that he move to Woodbury, and offered some advice for his successor: “Be open-minded, love the kids, listen, try to reach consensus, use data to make decisions and just work as hard as you can.”

Young is also head coach of the high school men’s basketball team. Hutchings said he has talked to Young about his balancing of basketball and his full-time job. “As long as the principalship is always the priority, and that doesn’t interfere with your role and your responsibility as a principal, I can support that,” he said.

Young said he hasn’t considered giving up coaching. “That’s my outlet, that’s fun. It keeps me — IB word — balanced,” he said. “I use that as a way to get kids to school. All my kids go to college.”

Grades

Hutchings said he would give SHMS a B- compared to the district’s other schools, which he gave straight B’s. He based this on “outreach we do to our parents, the opportunities we offer our students, the academics we provide for our students, the skills that our teachers have, the supports that we have for our teachers, the discipline, the safety.”

“If we had all A’s, there would be no point in me being here,” he said. Hutchings would not rule out having same-sex classes, uniforms or replacing administrators and teachers to improve SHMS. “I’m open to anything that will provide a better learning environment for our students.”

Young said he would give the middle school an A. “I think the best thing is the arts, the choices in levels that kids have. I think we have a plethora of sports clubs, activities that kids can get involved with, to make the middle school experience well-rounded, just not academics, you know, math, studies, social science, English,” Young said.

“Kids can find their niche,” he said. “We have a lot of different things that people can get involved in besides sports, and the sports just make it that much more meaningful for kids.”

“Not many schools offer three, offer four foreign languages for kids every single day. I have a lot of friends who are administrators of other middle schools and foreign languages are offered every other day. We offer Mandarin Chinese, French, Spanish and Latin every single day,” Young said.

Grosel, eighth grade English chairman, said he would give SHMS a B. “There’s a lot of good things going on, there’s a lot of new things going on. There’s a lot of people [faculty] working hard, and we have a lot of good students.”

Courageous conversations

Two SHMS teachers declined interview requests for this story in person. One guidance counselor referred comment to Caldwell, the district’s communications director, while another did not return phone and email requests for an interview.

When asked if she would be willing to be interviewed, one of the teachers said she was afraid if she spoke candidly she would lose her job.

Hutchings said she had nothing to fear. “I would never fire a teacher for speaking up. Actually, I would encourage it,” he said.

“The culture that I’m trying to lead, facilitate, is a culture of transparency and courageous conversations. What I tell our teachers, our administrators, our cabinet members, is that if we are not open and honest about things, then we’re not going to grow, and we’re going to keep on producing the same stuff,” Hutchings said.

“We have to stop pretending like everything is perfect, because no one’s perfect.”

This story appeared in Volume 84, Issue 4 (April 2014) of The Shakerite on pages 3-10.

Correction: The story has been revised to clarify middle school suspension data for the 2013-2014 school year. A total of 143 suspensions have been assigned so far this year. The number of unique students suspended is unknown.