152 Years Later, The Battle Begins Again

Confederate monument controversy leads to violence, stirs conversations within Shaker

Editor’s Note: After George Floyd was killed while in Minneapolis police custody May 25, some protests against police brutality included vandalization and destruction of statues and monuments raised to honor Confederate heroes, slave owners and Christopher Columbus. In 2017, protests occurred in Charlottesville, Virginia over the decision to remove a statue of Confederate Army General Robert E. Lee. Following the events in Charlottesville, former Editor-in-Chief Mae Nagusky (’20) wrote about the presence of such statues around the country and the arguments for removing and preserving them. The story appeared in print on Oct. 27, 2017. We repost it now because recent events have renewed its timeliness.

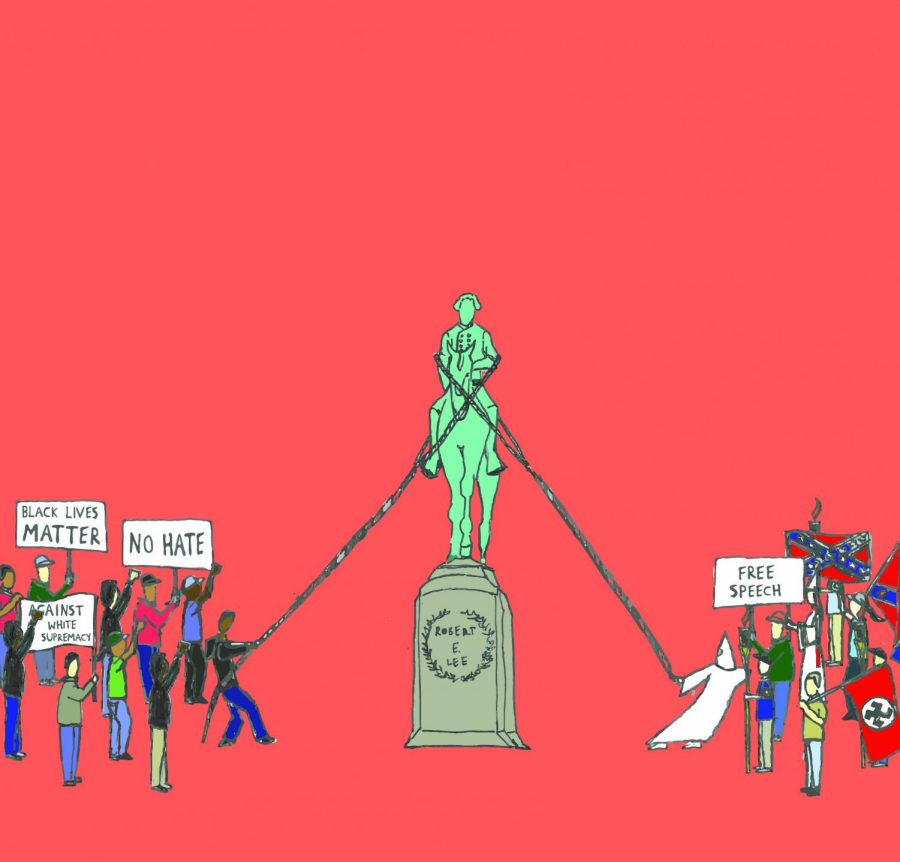

One woman killed. Twenty-one Confederate statues demolished. Brawls between white nationalists and counter-protesters mounting. Social media arguments brewing.

The Charlottesville City Council voted in February to remove a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee from Emancipation Park. In March, white supremacists filed lawsuits against the Charlottesville City Council, arguing that the city violated a state law protecting war memorials.

On May 13, a group of white nationalists protested the plan to remove Lee statue. On Aug. 11-12, white nationalists marched through the University of Virginia campus, carrying torches, in what they called a “Unite the Right” rally. They chanted, “White lives matter,” “Jews will not replace us” and the Nazi-associated phrase “blood and soil.” Counter-protestors assembled. Both groups were reportedly hit with pepper spray. The scene soon turned to chaos.

The next day, white nationalists and counter-protesters clashed hours before the rally was scheduled to begin. Protesters were injured, and the city declared an unlawful assembly at Emancipation Park. During the rally, a 20-year-old Ohio man accelerated his car into a crowd of counter-protesters, killing a 32-year-old woman and wounding at least 19 others.

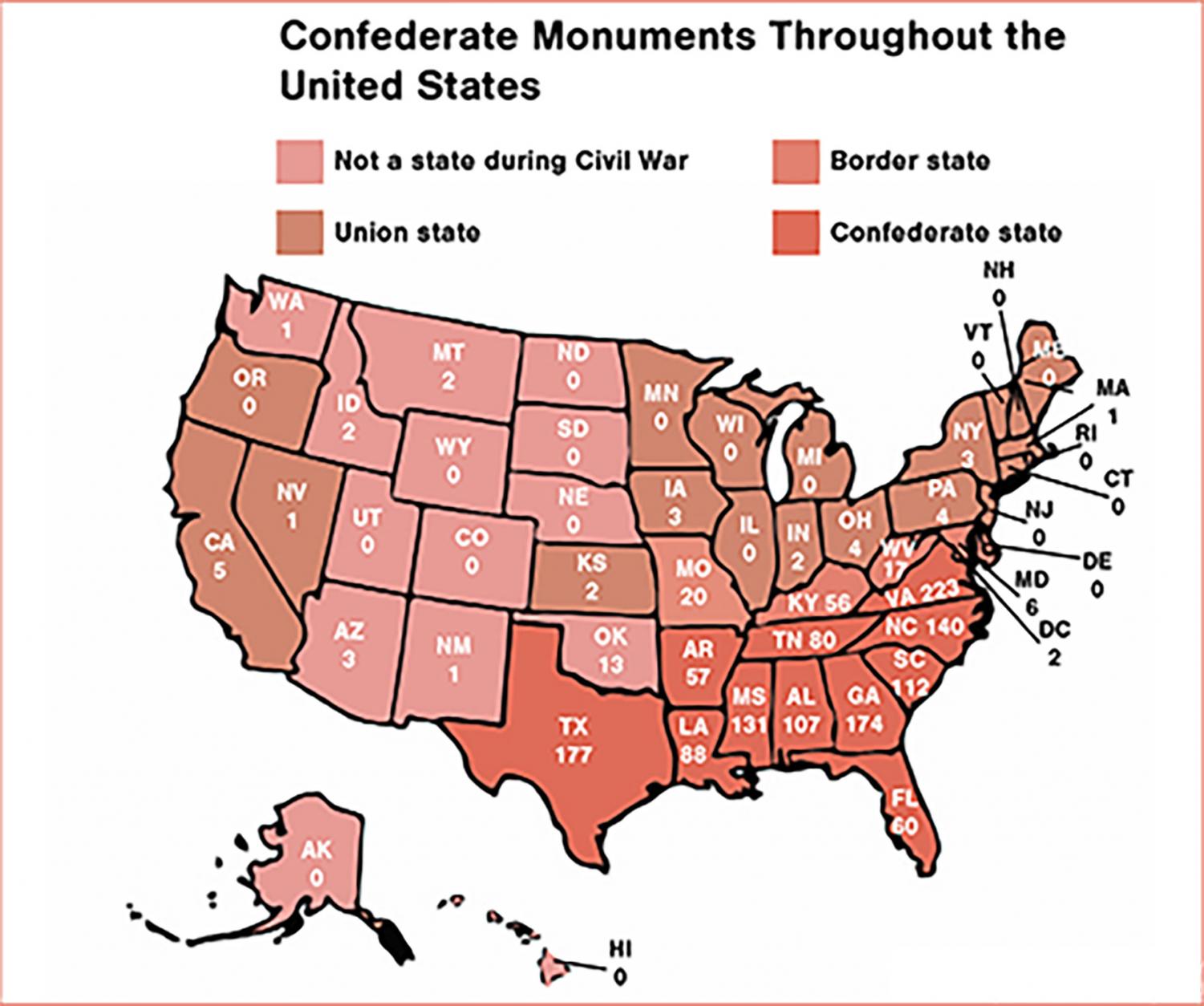

We don’t face Civil War artifacts in Shaker Heights, but more than 1,500 Confederate monuments are standing in 31 states. There are four Civil War memorials in Ohio honoring Confederate soldiers, including a plaque dedicated to Lee. In addition, 21 colleges have Confederate symbols on campus. When Shaker graduates leave this city, they may confront these symbols and the arguments that increasingly surround them.

As of Aug. 22, 18 Confederate monuments had been vandalized nationwide, including Ohio. As of Aug. 25, 32 statues had been removed. As of Aug. 28, 23 states had removed at least one Confederate monument.

On Aug. 14, protesters pulled down Durham County’s rebel soldier statue. Eight people face criminal charges for the act.Grace Lougheed

English teacher Jody Podl facilitated a class conversation Sept. 27 about current events in Charlottesville with her juniors and seniors.

The University of Texas is being sued by The Sons of Confederate Veterans for removing four Confederate statues from the main area of campus in Austin.

Almost all Confederate statues were built between the 1890s and 1950s, coinciding with the era of Jim Crow laws — a form of racial segregation and discrimination — more than 150 years after the Civil War ended. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center’s research, the biggest spike was between 1900 and the 1920s. Charlottesville’s Lee statue wasn’t erected until 1924.

The argument about keeping or removing Confederate statues boils down to whether they honor southern history or symbolize racism — and whether those two things can be separated.

Social Studies teacher and University of Virginia alumna Sarah Davis believes Confederate statues attempt to re-establish white supremacy. “I think it’s racist. I’ve always thought that; I’m from Shaker,” she said.

Principal Jonathan Kuehnle said Confederate monuments symbolize a wish to return to pre-Civil War circumstances. “Southern history is American history. We’re all in this together. However, the overwhelming amount of those monuments didn’t go up immediately after the Civil War,” he said. “They went up when it was Jim Crow, the KKK, when it was the whites in certain areas — and I say this as a white guy — trying to reassert their former dominance in the Civil War.”

“These were definitely racist gestures, and there’s no if’s, and’s or but’s about it,” Kuehnle said.

Davis said white supremacy is a legacy in American history. “So, the question is ‘Why is it so much more obvious to people?’ Part of it is that there’s a reluctance to combat domestic terrorism versus what we perceive as foreign terrorist threats, so it’s been able to grow,” she said.

Kuehnle said the argument to keep Confederate statues is invalid. “What, you’re proud that you committed treason against the United States of America? You’re proud of enslaving millions of your fellow humans? You put up these monuments at the exact time that we’re trying to offer equality and the right to vote and all of the other equity and access issues to all of our citizens, and now you’re choosing to put these up? It’s racist and treasonous.”

Davis expressed similar views. “We’re going to honor and remember and want our young kids to be like these Confederate heroes who fought against the United States government for the perpetuation of slavery,” she said. “I don’t understand how that’s a legitimate government message that should be supported by public taxes.”

While Shaker students may not be directly exposed to Confederate symbols or the debate surrounding them, teachers have made an effort to discuss the issue in classes.

Kuehnle said faculty are trained and willing to facilitate touchy conversations. “Shaker is willing to discuss controversial topics such as this, while other districts are scared of having these conversations,” he said.

Facing History and Ourselves is a national teacher training program that Shaker began collaborating with last year. Facing History provides resources and ideas about how to discuss critical current events and controversial issues in the classroom.

English teacher Jody Podl facilitated an in-class discussion about Confederate statues using questions from Facing History. “I think it’s a little bit more complicated than, ‘Should we keep these statues up, or take them down?’ Everything is a little bit more complicated than that,” she said.

Podl emphasized the importance of learning about and discussing controversial issues.

“I think part of the reason we’re in the situation we’re in is because people only want to be with other people who think the same way as they do, and that’s not helpful,” she said. “I think we have to be able to listen to each other and respect different opinions and, hopefully, we can find some common ground or even come up with possible solutions that are the result of listening to each other.”

Podl said that during the discussion, some of her students were uncomfortable. “But at the same time,” she added, “I don’t think anybody felt that their voice wasn’t heard or that they didn’t have an opportunity to say how they felt, and I’m hoping that people actually listened to each other. I don’t think you can go anywhere if you’re not going to have the first conversation.”

Podl said discussing what to do with Confederate statues offers a chance for important reflection. “Removing the statues will not prevent racism, and it’s not going to solve the problems that we have in our society with systemic racism, but it does make us think about it, and that’s an important step in the process,” she said.

“The real question is, ‘What are we going to do to fix these problems?’ Certainly, this is one step, but I hope it’s not the only step. I hope it’s the beginning of some work, not the end. That is what makes me worry,” Podl said.

Senior Jalan Morgan said he wants Confederate statues to be removed. He said keeping them up is a sign to racists saying, “You can continue being racist and a menace to society, without any repercussions.”

Junior Daniel Connors said the statues should come down because they represent hate. “There’s no statue of Hitler in Germany,” he said.

Senior Will Clawson supports removing the statues because, he said, they represent a period of hate, violence and slavery. “They should not be placed in a public space of honor as they signify the complete opposite,” he said.

Art teacher Meryl Haring said statues could be preserved in museums instead of on campuses. “I think they could have the same purpose of preserving history in a museum or out of the public eye, so that those that it reminds of a hard past — they don’t have to constantly be passing it daily,” she said.

Junior Josh Skubby said their rightful place is in a historical collection acknowledging the crimes of the figures depicted. “At the very least they should be condemned while remaining for the preservationist purposes,” he said. “But again, best case scenario, they are removed and preserved as symbols so we may never forget the worst atrocity in American history.”

Olivia Frierson (’14), a senior at UVA, also suggested moving the statues so they could be “acknowledged and not forgotten.”

“They are erected in such a way that they are celebrated, as they are in a lot of places here in the south,” she said. “So, I think it’s important to make that distinction between celebration and remembering history, and I think that’s the debate that’s really going on right now.”

James Caffrey (’15), a junior at UVA, said that at the beginning of class this year, his professors clarified that they oppose white supremacy and offered resources to help anyone concerned about the events in Charlottesville. He said professors also held a mandatory two-hour seminar in early September to discuss the importance of diversity.

Art teacher Kristina Walter emphasized the importance of student involvement in current affairs.

“Students are the people that are going to be making important decisions in five or 10 years, and I think that it’s really important for students to be actively involved in current topics like this,” Walter said.

Frierson had a similar view. “I think that because college students are the next generation, more conversations on college campuses are super important to end this in the future,” she said.

“I think students have to live in a world just like everyone else, so they should have their voices heard about their opinions on a lot of the issues surrounding them,” Caffrey said.

Clawson said white supremacy has grown because of President Donald Trump. “He has encouraged supremacists and his supporters to act upon others spreading hate and violence. The president continues to encourage spreading hate by not specifically saying what they are doing is wrong,” Clawson said. “They look up to the president to protect them because they know he will.”

On Aug. 13, the day after a counter-protester was run over and killed by a white nationalist, Trump said, “We condemn in the strongest possible terms this egregious display of hatred, bigotry and violence on many sides — on many sides.” Trump was sharply criticized for treating the white supremacist groups and counter-protesters equally with that statement.

Frierson said white supremacy has gained momentum because of the current political climate.

“I think that these ideas always existed in the United States, but I think the dialogue in this country has really opened up for people to be more explicit and there to be no consequences for those explicit actions,” she said. “It’s a lot more prevalent now because of the way we’re having these conversations and the openness and more explicit behavior shown by people in the United States today, whether they’re political figures or just everyday people.”

On Aug, 14, Trump criticized white supremacists. “Racism is evil,” he said. “Those who cause violence in its name are criminals and thugs, including the [Ku Klux Klan], neo-Nazis, white supremacists and other hate groups that are repugnant to everything we hold dear as Americans.” However, the next day, Trump defended his original statement and blamed “both sides” for the violence in Charlottesville.

Haring said white supremacists feel they can speak out because Trump has their back. “Anytime it’s newsworthy for the president to say, ‘White supremacy is bad,’ that should just be a given,” she said. “The fact that that’s a big deal to hear the president say that, that’s not great.”

Frierson said she hopes this conflict will end. “I think that eventually there will be a turning point where people realize that the things going on are not OK, and my hope is that we’ll come together as a community and politically,” she said. “Eventually, we’ll be able to solve some of these issues, but right now, I don’t see that in the forefront of our future.”

A version of this article appears in print on pages 6-11 of Volume 88, Issue 1, published Oct. 27 2017.

Comment using your Facebook, Yahoo, AOL or Hotmail account