Is Disrespect On The Rise?

Discipline statistics don’t reflect frequency of disregard, insults and threats teachers report

“Who the f*** are you?! Are you some f***ing sub?!”

These profane questions, uttered by a student after school one day, were directed toward a teacher.

Another student tried to insult a teacher by calling her a lesbian. A student once accused a teacher of getting angry at the class because she “hasn’t gotten any d***.”

Students have told teachers to “get the f*** out of my face.” One student yelled at a teacher for their “breath being poor.”

A teacher told a student to watch his language, and he responded with “Who the f*** does this bitch think she is?”

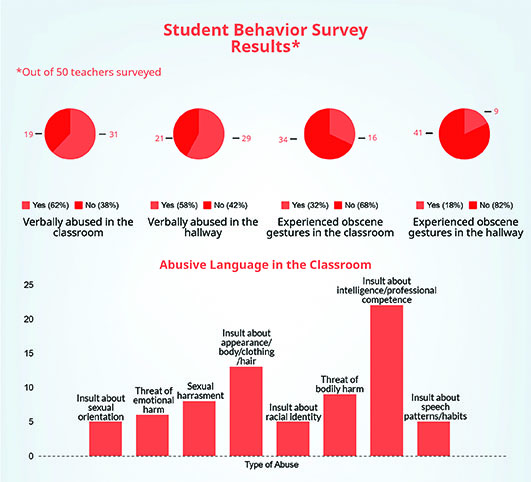

The instances above were shared with The Shakerite through a survey of high school faculty and interviews. The Google survey was sent via email to 149 teachers, and 50 teachers completed the survey within the response period. Sixty-two percent of respondents said they have been verbally abused in the classroom, and 58 percent said they have been verbally abused in the hallway.

The survey indicates that teachers experience different kinds of disrespectful behavior, from rude conversations to threats of violence. In comments teachers entered in the survey, teachers gave examples of verbal abuse that included enduring racial or ethnic slurs; being called a swear word; being the target of vulgar language; being yelled at; or receiving threats and insults.

One student told a teacher to meet him off school property and threatened to fight him. Another student lifted a fist as if to punch the teacher. Another threatened to harm a teacher physically because of a grade the student received. Another student told a teacher that she should watch out or she “was gonna get it.”

In some cases, teachers reported that students said they would enlist family members in their threats.

A student harassed a teacher and then threatened that his mother and uncles would find the teacher. Another told a teacher that his uncle carries a gun — and then looked up the teacher’s address on a county website.

In other instances, misbehavior extended beyond words. Two students began fighting during a final exam, and one student pushed the teacher while she was trying to break it up. When a teacher tried to exit the building, a student blocked her path. One student pretended to masturbate behind his teacher.

Librarian Laura Daberko and Spanish teacher Kimberly Ponce de Leon said they have been told to “f*** off” and called a “bitch” by students.

Teachers also reported that students insult their practice. A student accused Roy Isaacs, who teaches Core/Honors U.S. History and History of Popular American Music, of spending too much time talking about his Hispanic heritage in class. Isaacs is European-American and Indian — not Hispanic.

“I found that to be a little more bothersome than someone using a foul word or getting angry — if it’s based in some bigoted misunderstanding of who I am and what my intentions are,” he said.

Despite these behaviors, the high school administration shared disciplinary statistics Feb. 12 that portray a decline in suspensions during the first semester this year. Principal Jonathan Kuehnle shared similar statistics from Shaker Middle School last spring. And high school disciplinary referrals for the first semester of this school year and last school year are dominated by attendance infractions — not instances of student disrespect.

At the high school, 2,325 referrals were written in the first semester of 2016-17 and the first semester of 2017-18, combined. Four percent were written due to vulgar language, threatening language or sexual misconduct. Seventeen percent were due to disruptive behavior or failure to comply. One percent were written for harassment or intimidation.

Sixty-nine percent were written for tardiness or class-cutting.

The contrast between teachers’ survey responses and referral rates for disrespectful behavior suggest that the behaviors are not being successfully addressed, or that teachers choose not to write referrals, or that teachers cannot write referrals for hallway behavior because they do not know students’ names.

Only four teachers surveyed said they are more frequently disrespected in their classrooms than in the hallway.

“We have to understand that, in the hallways, there are teachers and students interacting that maybe don’t know each other, so the relationship isn’t there,” Dean of Students Greg Zannelli said.

Kuehnle implemented a policy Jan. 22 requiring students to wear their student IDs at all times. According to Kuehnle, the policy is primarily a security measure that allows security personnel to easily identify intruders. For teachers, the policy would allow them to identify students who ignore instructions from teachers or who respond disrespectfully.

Few students, however, continue to wear their IDs.

When science teacher Maggie Parks asks students to follow rules in the halls, some respond, “You’re not my teacher.”

“It’s hard because if I don’t know that kid by name, there’s really not a lot I can do about it, unfortunately,” Parks said.

Ponce de Leon reiterated this experience. “Students that don’t know you in the hallways feel like they can get away with disrespect because you don’t know who they are,” she said. “Most students, if they know you, they’re respectful. But, if there’s an anonymity to them, they might take advantage of that and be disrespectful.”

However, Ponce de Leon said the ID policy has been useful in identifying students. “If a student has an ID, I can address them by their name,” she said. “Right now, I don’t feel like students are in favor of the ID’s, and I’d like them to see the usefulness of that.”

Half of the teachers surveyed said they notice more disrespectful behavior than they did earlier in their careers.

Daberko said she hears more profanity in the halls. “The language has gotten worse. There is less regard for following the rules,” she said.

Mathematics teacher Angela Harrell said it has become normal to hear profanity in the hallway. “I’m like, ‘What in the world? Why is there so much trash talk?’ But then I have a conversation about it,” she said.

Harrell, who has taught at Shaker for 22 years, said teenagers today are exposed to more profanity than they were 20 years ago. This exposure changes their opinion about what behavior is acceptable. “Teenagers are teenagers,” she said. “You have to actually teach people about the importance of language and what it means and what’s appropriate here and what’s not appropriate here. That’s an environment thing.”

A security guard, who spoke on the record but was granted anonymity to discourage reprisals, said there are 12 security guards stationed throughout the building until 4 p.m., and five after 4 p.m.

He said the building can be chaotic after school, especially if there is an athletic event scheduled. “We have to babysit for that two hours,” he said. “Because they’re kids, and that’s what kids do — they get in trouble.”

Isaacs said students sometimes misbehave to relieve pressure. “If a student’s erupting in an actual physical fight, they’re having this emotional release,” he said.

The security guard said a lack of attention at home may cause students to seek it at school. “If you’re my child and all I show you is love, you’re not going to do anything but go out there and show the world love,” he said. “But if you’re my child and I’m not paying attention to you, it’s going to show.”

Sophomore Julia Schmitt-Palumbo said students act out because they don’t like authority, or because the teacher doesn’t give them enough attention. She believes that punishment won’t stop the student from acting out. “But it will show them what they are expecting if they plan to continue doing it, and if people don’t want that, then it may hold some back,” she said.

Zannelli said more respect is given in a one-on-one situation. “I have to talk to the student and teacher and see where it came from, what was said, the parameters of it,” he said. “The key component is bringing the two together to find out what’s the issue and build that relationship.”

Out of 50 teachers surveyed, 38 said they are most frequently disrespected in the hallways.

Isaacs said that tolerance plays a role in the amount of consequences he assigns or referrals he writes. “I think that I’m one that tries to not let my ego be the front of my teaching and then get into a power struggle with that kid and try not to be offended,” he said. “There’s other reasons the kid doesn’t want to do the work or to be controlled and told what to do.”

Isaacs added that a lot of conflicts with students can be stopped with a conversation. “I’m not somebody who writes a ton of referrals and I don’t really see them as doing a lot of good,” he said.

Zannelli said students are disciplined on a case-by-case basis. “If students are swearing out one another, my first instinct is to bring those students together, find out what the issue is and repair their relationship,” he said.

Zannelli and Director of Student Affairs Ouimet Smith both mentioned Shaker’s restorative practices, which they first employed in 2013, as a strategy to curb disrespectful behavior.

Restorative practices comprise two components: a proactive component in which students participate in class discussions, called community circles, and a reactive component in which teachers and administrators hold meetings, called restorative conferences, with misbehaving students. Shaker Middle School students began community circles in 2014, and circles were instituted in ninth-grade English classes this year.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, restorative practices are “a set of informal and formal strategies intended to build relationships and a sense of community to prevent conflict and wrongdoing, and respond to wrongdoings, with the intention to repair any harm that was a result of the wrongdoing.”

These methods depart from traditional punitive discipline, such as assigning suspensions or detentions, which aims to punish the student for misbehavior and thereby discourage further offenses.

Since instituting restorative practices, the district has reported declines in disciplinary referrals and suspensions. In a PowerPoint comparing first semester discipline data at the high school in 2016-17 and 2017-18, the district reported a 38 percent decrease in infractions for disruptive behavior or failure to comply and a nearly 18 percent decrease in infractions for vulgar or threatening language from the first semester of 2016 to the first semester of 2017.

The PowerPoint also documented a 13.5 percent decline in detentions, a 60 percent decline in Saturday School assignments, a 35.6 percent decline in in-school suspensions and a 14.4 percent decline in out-of-school suspensions.

This decline mirrors the trend in other states. According to the California Department of Education, “suspensions declined by a remarkable 46 percent” and expulsions decreased by 42 percent from 2011 to 2017.”

Isaacs encourages students to practice code-switching. According to Isaacs, someone who code-switches changes behavior and language to accommodate different people and situations.

“Not only is [the disrespect] wrong today and in my class, but it’s going to hurt you in the long run,” he said. “Consider really trying to switch how you talk in front of your grandparents, how you talk in your religious institution, how you talk on your walk home. It’s going to be different for each one.”

Sophomore Charlotte Cupp said it becomes habitual for students to disrespect teachers because they don’t recognize what they’re doing. “You should treat your teachers how you would treat another human,” she said. “If everyone treats others like a human being, we wouldn’t have these problems with hatred and disrespect.”

A version of this article appears in print on page 6-11 of Volume 88, Issue III, published May 18, 2018.

Comment using your Facebook, Yahoo, AOL or Hotmail account