New Testing Regimen Begins with 325-Minute Pilot Test

Shaker will pilot one of Ohio’s new End-of-Course Exams in April, a 325-minute English test for ninth graders, to be administered by computer.

A sample of freshmen will take the test, just one pilot of 10 end-of-year assessments currently in development by the Ohio Department of Education. These tests aim to assess “college- and work-readiness,” according to the ODE website. A coalition of 18 states and the District of Columbia called the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers, or PARCC, is creating six of the 10 assessments, those testing math and reading proficiency, to “measure 21st century content and skills in math and English.”

The math exams currently in development will assess proficiency in algebra I and II and geometry, while the three reading tests concern English language arts 1, 2 and 3.

Included in the 10 end-of-year exams in development are computer-administered tests in science and social studies, including physical science, biology, American history and American government. Ohio is creating these four tests separately from PARCC.

As these 10 exams are finalized, they will be administered to all Ohio public high school students.

Administering the Pilot

Only a sample of Shaker’s ninth graders will pilot the April exam, which tests English language arts 1. According to Principal Michael Griffith, the method of choosing those students will be “probably random.” To gain feedback from team, college preparatory and honors English students about the assessment, “we probably are going to be looking at it more in terms of how many sections,” he said.

“There will be four ninth grade classes piloting PARCC,” English Department Chairwoman Elaine Mason said. “That’s all we know right now.”

Shaker’s April pilot test will have no bearing on anything other than feedback to the school and the exam writers, Griffith said.

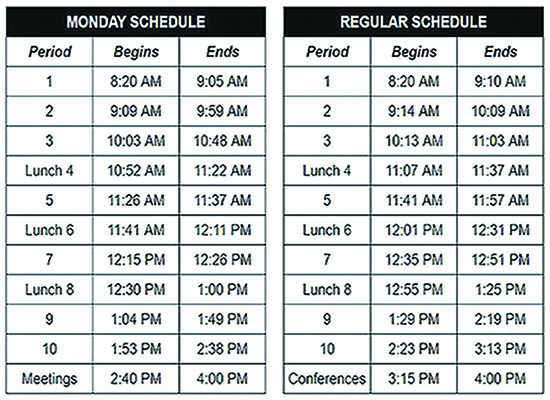

Details concerning that pilot test’s April administration are still unclear. “We have not determined yet how we’re going to actually implement it,” Griffith said. Three segments comprise the 325-minute exam, two of which “might be in the neighborhood of a class period or slightly longer than a class period.” In that case, “we might be able to pull it off where it’s a slightly adjusted day, but not crazy,” Griffith said. “So we don’t have to do something, at least for now . . . of major impact to the school day, like delayed starts.”

Lesley Muldoon, the associate director for PARCC state engagement and policy, said PARCC is “trying to make sure that no student runs out of time to complete the test.” As such, “for the pilot tests this spring, we will take about 50 percent more time than we think students will actually need,” hence the length of Shaker’s pilot exam.

According to Griffith, Shaker will pilot the ninth-grade end-of-course English exam because the ODE requested schools from across the state to pilot these tests. “We didn’t get to pick our subject area. The subjects were offered to us,” he said. “[The ODE is] probably testing out questions. . . . They’re probably trying to look at the whole body of the test, probably trying to look at length. I suspect they’re trying to get feedback about everything.”

“They’ve developed the questions, but they need to determine how the questions will work when administered to actual students,” Shaker’s Director of Research and Evaluation Dale Whittington confirmed. “They couldn’t embed questions like that into an existing test because the test hasn’t been administered yet, so that’s why they’re doing the pilot. It’s a way of getting an idea of how these questions are going to work so that they don’t end up putting bad questions on the test when the test counts.”

The 10 tests are “all at different points of readiness in terms of either being written or being piloted,” Griffith said. He said the state is “trying to prepare pieces and parts to begin next year,” including the English language arts 1 exam that Shaker will pilot.

“As I understand it, we were asked if we were interested in participating, and we said, ‘Yes,’” Griffith said. By piloting the test, Griffith said he believes the school will gain “a snapshot or a sense of what the direction is, and what is being thought about in terms of the structure of the assessment,” as well as “some generalized feedback in terms of what this might do in terms of the rigor and the challenge.”

With that information, Griffith believes that “a year from now, we’ll be sitting in a different place, where we’ve got a lot of the structure there, and then we’re talking about the quality of the structure and tweaking, which will be a good place.” However, this year “is just a lot of running and trying to get all the pieces and things in place,” he said.

English teacher Carol Boyd is resigned to the impact of testing on instruction.

“I see it as a necessary evil,” Boyd said of the upcoming pilot test. “We’ll learn to manage it because we have to.”

The time required to administer the pilot test worries Boyd, who teaches 9 Honors English. While one day of testing would not negatively impact her curriculum, a week of test-taking would create a significant interruption. In that case, “I would not be able to cover all the curriculum I need to cover,” Boyd said. “I wouldn’t be able to put as much on my final exam.”

In addition, the ODE requires administration of end-of-year assessments in American government and U.S. history this year while it finishes developing its own end-of-course exams in those subjects. Shaker’s CP U.S. History and U.S. Government exams will suffice for those assessments in the meantime.

Shaker selected the CP exams because they met the state’s description of a standard. “We said our college prep is our standard,” Griffith said. “It’s a temporary measure.”

Acquiring the Technology

This year, Shaker’s computer supply should suffice for the relatively small group of freshmen who will take the April pilot exam. “Between our labs and our COWs [Computers on Wheels], I think we’re going to be fine internally to be able to pull it off this year,” Griffith said. However, in the future — when more End-of-Course Exams are administered and taken eventually by all students — the district will face challenges.

“There will be logistical problems, technological problems, resource problems,” Griffith said. “There’s no end to all of the pieces that we’re going to have to figure out to make it doable and reasonable given the expectations, and also with the same goal in mind that we always have: trying to minimize, as much as we can, the negative impact on the instruction.

“Our goal is increased [technological] capacity. We know that already. We were already on that track and have been even before this,” Griffith said. The science department possesses computers on wheels — carts housing netbooks that students may use for research during class — as does the library. “Our intention is to try to get to a point where we have maybe three [COWs] in every single department,” Griffith said. “During testing times, if you took all of those and combined them together, you’ve got a fair arsenal, so to speak, of those that you could pull into spaces and manage the testing with.”

Currently, Griffith plans to use the netbooks housed in the school’s COWs for the pilot exam, stating that “in all likelihood we probably have to.” However, “it’s unclear whether the netbooks are the best tool for what this is going to be about,” he said, citing concerns about the devices’ speed. “If it turns out that we’re not clear that the netbook is the best tool, then we’re going to have to find a Plan B to pull it [the testing] off.”

Kathy Fredrick, district director of library media and instructional tech, said the netbooks should work. “They do meet the specifications that PARCC has set up for the devices that can be used,” said Fredrick. “Part of the nature of the pilot is that they’ll be testing all sorts of devices.

“We know that there are problems when [the netbooks] first load, and we are working on those issues,” Fredrick added. “My concern is having the pipeline that we need — the bandwidth that we need to take the test.” This year, with relatively few people taking the test, capacity should not be a significant issue, she said. However, in coming years when more students take the exams, it could be a problem.

The Government’s Guidelines

Muldoon wrote in an email that when the End-of-Course Exams are officially administered, “PARCC will offer a 20-day testing window” for its exams, though “states may opt to use a shorter test period within that window.” She said PARCC estimates that “most schools will be able to complete testing in as few as five to 10 days.”

Currently, Ohio’s State Board of Education, whose Graduation Committee drafted the plan for the End-of-Course Exams’ administration, does not have a timeline for how many days schools will need to complete testing altogether.

The Graduation Committee’s plan, formally approved in November, dictates that the End-of-Course Exams will replace the Ohio Graduation Test. Each exam will be worth a maximum of five possible points. Students who take all 10 tests will be required to earn a minimum of 25 points total to graduate.

According to the board’s plan, the class of 2018 — currently eighth-graders — will take five End-of-Course Exams as part of their graduation requirements; the class of 2019, eight; and the class of 2020 onward will take all 10 exams.

However, C. Todd Jones, chairman of the State Board of Education’s Graduation Committee, said “districts have the possibility of eliminating the first math and English end-of-course exams.” That decision would reduce the number of end-of-course exams administered at a school to eight. The two tests that districts may choose to eliminate assess proficiency in algebra I and English language arts 1.

The math and English end-of-course exams are elements of a new testing system called the Next Generation Assessments, created by the 18 states and the District of Columbia in the PARCC consortium. According to PARCC’s website, the Next Generation Assessments aim to align with “the full range of the Common Core State Standards.”

The Common Core State Standards Initiative was formally developed in 2009 by the National Governors Association. The Common Core includes standards for mathematics and English language arts, to “provide a consistent, clear understanding of what students are expected to learn, so teachers and parents know what they need to do to help them,” according to the Common Core’s website. In mathematics, each grade level and domain of the subject has different standards. In English language arts, different standards exist for different categories, such as “Reading: Literature,” “Reading: Foundational Skills,” “Writing” and “Speaking & Listening.”

Adoption of the Common Core standards is not mandatory. The initiative “is a state-led effort . . . being driven by the needs of the states, not the federal government,” according to its website.

The state of New York piloted tests associated with the Common Core in April 2013, prompting student and parent protests alike. According to The New York Times, the test results showed “that about 31 percent of the state’s students in third through eighth grades met or exceeded the proficiency standard in language arts . . . down from about 55 percent in 2012 and 77 percent in 2009, when the state tests were easier.”

According to PARCC’s website, the consortium, using a $186 million grant from the federal Race to the Top program, aims “to develop a common set of K-12 assessments in English and math anchored in what it takes to be ready for college and careers.” Pearson Assessment, whose tests are administered in more than 70 countries, and the Educational Testing Service, which writes the SAT and Advanced Placement exams among others, develop PARCC’s exams. Race to the Top promotes reforms in education nationwide, rewarding schools’ educational improvement with funds.

Race to the Top also affects Shaker’s involvement in the pilot tests. “We’re doing the full deal as a district, and we are completely immersed and involved, I believe, in all the different elements [of testing], and that is, I believe, strongly connected with the fact that we are a Race to the Top district,” said Griffith. “If we weren’t, I think it wouldn’t have eliminated this; it would have slowed it down.”

In a year, he thinks, schools not associated with Race to the Top will adopt all the exams Shaker currently administers and “will be going through some of the growing pains that we’re facing. And we’ll be in a position where many of the things are more solid,” he said.

Further Testing in the Future

However, the number of standardized tests administered in Ohio will only increase in upcoming years. “The state is going to be rolling out — they need a measure of what they call ‘college and career readiness’ that at this point is just a general assessment, and they’ve made a contract with ETS [Educational Testing Service] to use the PSAT,” Whittington said. Next year’s sophomores will take this required PSAT in October. “It cannot be used for any grading for students. It can’t be used for college admission or anything like that. That’s forbidden,” Whittington said.

At a later date, however, Whittington said “the state may break that contract [with ETS].” She clarified that “it’s all rumor at this point,” but said the state is considering a “switch over to something called Aspire, which is being developed by ACT to replace the PLAN and Explore [tests].”

“On the books right now, technically the PSAT is being required for next year,” Whittington said. “Will that be the case a month from now? Maybe not.”

High school students will not be the only ones hit with increased testing. Students in grades three through eight will also take end-of-course exams developed by PARCC, with both March and May components. The “performance-based” March component will be handwritten, while the May part will be administered by computer.

Like the exams at the high school, the March parts of the English exams for fourth- through eighth-graders will take approximately three and a half hours to complete in three shorter sessions, according to Muldoon. “Third graders will have a shorter set of essays and will only spend about two and a half hours on this part of the PARCC assessment,” Muldoon wrote in an email. For all grades, the March components of the math exams will take about two hours. The May segments of both exams will also take about two hours to complete.

Third- through eighth-graders “will also be taking performance-based assessments developed by a different testing company [than PARCC] in science and social studies,” Whittington said. Those science and social studies exams are being created by the state of Ohio.

These exams come in addition to requirements from the new Ohio Teacher Evaluation System, enacted last year, which include the Student Learning Objectives tests administered to every public school student in every subject in the fall and spring, or in January for semester courses.

Boyd does not think the ninth grade English pilot test will affect her students’ preparation for SLOs. “I don’t think it would because they don’t prepare for this [pilot] test,” she said, and “you wouldn’t prepare for your SLOs.” However, Boyd added, “I don’t know enough about this test to really say.”

Griffith was unsure about what effects the final end-of-course exams might have.

“In theory, I think they [the End-of-Course Exams] have potential. In practice, I’m not convinced,” Griffith said. “I think they have great potential because the kinds of questions they’re asking are really good questions. I’ve seen some of the sample questions in math and some of the other areas, and they are very good, conceptually-based questions, and you really have to understand and have good knowledge. At the same time, when I say ‘in practice’ — the bombardment of testing, and the volume of testing, and the consequences to instruction are not necessarily a very good thing. In fact, I would say they’re clearly not a good thing.

“It’s just the quantity of it, and all of it being tossed on at the exact same time . . . I’m not convinced that that hasn’t had a very detrimental impact on their ability to focus on the instruction in the way that we feel is best,” Griffith said. “It has great potential to distract us from the true teaching that needs to go on, so I’m concerned about it. I’m concerned it’s taking away the sense of time and motivation and energy that teachers would have been putting into their instruction and working with young people.”