Free, But Not Easy

Shaker athletes and coaches describe the preparation and pressures that go into free throw shooting

August 25, 2020

Dribble three times. Pause. Spin the ball. Shoot.

Repeat.

Despite practiced routines, basketball players at all levels of competition can struggle to consistently make a shot misleadingly described as “free.”

And despite an NBA that employs more knockdown three-point shooters and ever-more athletic players, one thing has remained consistent: free throw percentage. Since 2000, the NBA league average has consistently hovered around 75 percent. LeBron James carries a career average of 74 percent.

The free throw, along with basketball itself, was created in 1891 by James Naismith. Originally, the free throw line was 20 feet away from the basket. It was moved five feet closer in 1895 because players had little to no success from the original distance. Teams also originally chose the player who took the foul shot, no matter who was fouled. In 1924, a rule change required the player who was fouled to shoot the free throws.

According to an NCAA study of every Division I men’s basketball team since 2001, teams that shot more free throws won more games. “Teams could shoot dozens of 3-pointers a game, or none, with virtually no impact on their win percentage. The same goes for 2-point field goals. But free throws? That’s where we saw the difference,” the study’s authors stated.

But in the age of social media, pressure to perform well in big moments is higher than ever, as people watch game highlights and voice their opinions instantaneously, anonymously and at a digital distance.

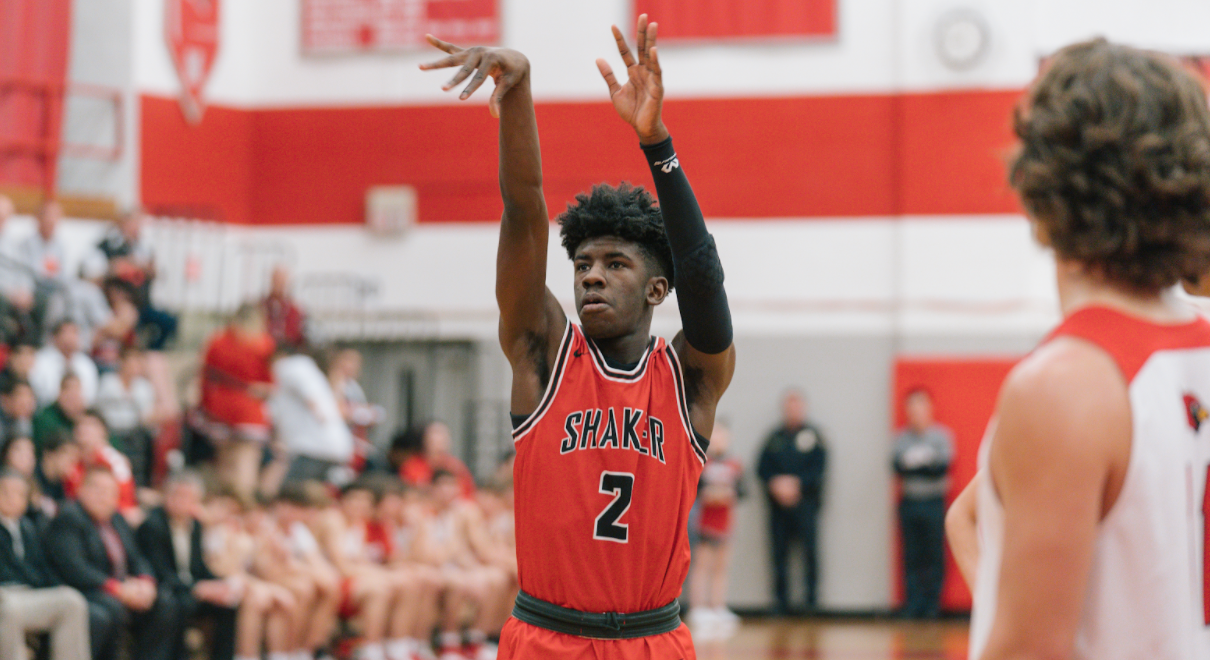

Junior men’s basketball guard DeAndre Hall said his worst nightmare is choking: the failure of an athlete to maintain performance in big moments. “Whenever someone misses high-stake free throws, it is always over social media after the game,” he said. “I know I never want to see myself in that position, and I never want to see myself on Instagram missing a big shot, so I try to re-create those moments when I’m practicing by myself.”

Dan Cohn, who has a masters degree in sports psychology and works at Greene Clinical and Sports Psychology outside of Philadelphia, said he guides young athletes to overcome psychological pressures. “A lot of it has to do with the magnitude of the moment.” Cohn said.

“Typically, I help them develop some strategies to deal with the nerves that they might be feeling in that moment; how to build their ability to focus their attention on the task at hand. I make sure the athlete feels comfortable when talking to them, while giving them the proper space they need and reminding them it’s confidential. In some ways, I’m a mental coach for them,” he said.

Cohn said that a basketball player’s thought processes can affect their performance.“If they have a high level of belief, it’s more of an automatic process,” said Cohn, ‘but if it’s something that they struggle with and they doubt themselves, sort of dealing with their own thoughts about free throw shooting might be part of the pressure.”

One player accustomed to high pressure moments – especially at the free throw line — is men’s varsity point guard Danny Young, Jr. Young, a sophomore, made 13 of 14 free throws against Lutheran East Feb. 5 to help the Raiders defeat a team that played for the Division III state championship last year.

“Free throws are all mental,” Young said. “You can be the most athletic and have the best handle, but at the end of the day, games are decided by free throws. I train my free throw every day.”

Last March, in the district quarterfinal game, the men’s basketball team hosted University School in front of a sold-out crowd. With the Raiders leading most of the way, University School managed to tie the game late in the fourth quarter. After Young, then a freshman, was fouled in the waning moments, he had to hit two free throws. He calmly drained both despite a chaotic environment and helped Shaker win, 53-49.

One way to preserve concentration in a chaotic environment is to perfect a pre-shot routine and execute it every time you shoot. Every basketball player creates a unique pre-shot ritual, but why is it important?

“If you’re in a fast paced, intense game, it’s important to calm your team down, especially yourself,” women’s varsity head coach Fred Howery said. “Having a consistent routine you’re used to helps your focus and makes you comfortable, which is what you want.”

Young relies on his routine.

“I always take my three dribbles and pause. I always try to stay calm and not try to rush my routine,” Young said. “The situations we do in practice always help when it translates to the game, whether it be 20 seconds, 10 seconds or five seconds left. We are all used to these types of high-pressure situations in close games.”

Clutch time — the term for the last few minutes of the fourth quarter — can be stressful and intimidating for players. “I remember when I was a freshman, and I was always nervous during my games,” senior women’s basketball forward Adaeze Okoye said. “That really had an effect on how my shots were, especially my free throws. My free throws aren’t perfect, but as I’ve gotten older, I’ve felt more comfortable at the line.”

Howery said he puts his players in high-pressure situations during practice to prepare them for games. “You’re not going to be able to come in from an off-season and expect to be good at shooting — especially free throws — if you don’t work on it all year round,” he said. “We always try to practice a lot from the line and do some games to put them in pressure situations so they’re comfortable for when games come.”

Junior guard Tahsja Jackson, who leads the women’s team in scoring with 9.6 points per game, described one way her team practices free throws. “At the end of practice, we have to make seven free throws in a row in order to go home,” she said. She described a time when she stayed late trying to accomplish that task. “One night, I stayed over an hour after practice was over, shooting free throws,” she said.

Hall described a drill the men’s team practices to improve their foul shots. “During any type of break or after we do big runs, we do this ‘Ray Allen,’ and if you hit all net for your free throw, that’s two points. If it rolls around the rim, that’s one point, and if you miss it, it’s negative one,”

Allen, the all time NBA leader in three pointers and a career 89 percent free-throw shooter, is widely regarded as one of the best shooters of all time. The Shaker men’s team named the drill after him because of his success. “We all try to get to 20, and whoever gets to 20 wins, and whoever doesn’t win has to do push ups,” Hall said. “That’s a big reason, combined with my work ethic, on why I’m such a good shooter.”

Howery said that ultimately, doing well at the freethrow line depends on practice and staying calm in the moment. “Success in high-pressure moments takes tremendous focus, concentration and a lot of practice. It’s you, 15 feet from the rim, and everything you’ve been working on with your form,” Howery said. “It’s really you zoning in on that rim and putting your hand in the cookie jar.”

Young is confident in his ability to knock down the big foul shots. “At the end of the day, it comes down to practice and repetition. I know if we’re down, and I get fouled, and I need to make two free throws, I always think, ‘Come on! Come on!’ and I’m always eager for it to go in,” he said.

“But, no matter how big the environment or moment is, I usually stay calm, and I know it will go in — because I practiced them.”