Tracking, An Unfair Race

Over time, class placement can affect the experience Shaker students of color face compared to their white peers.

January 21, 2020

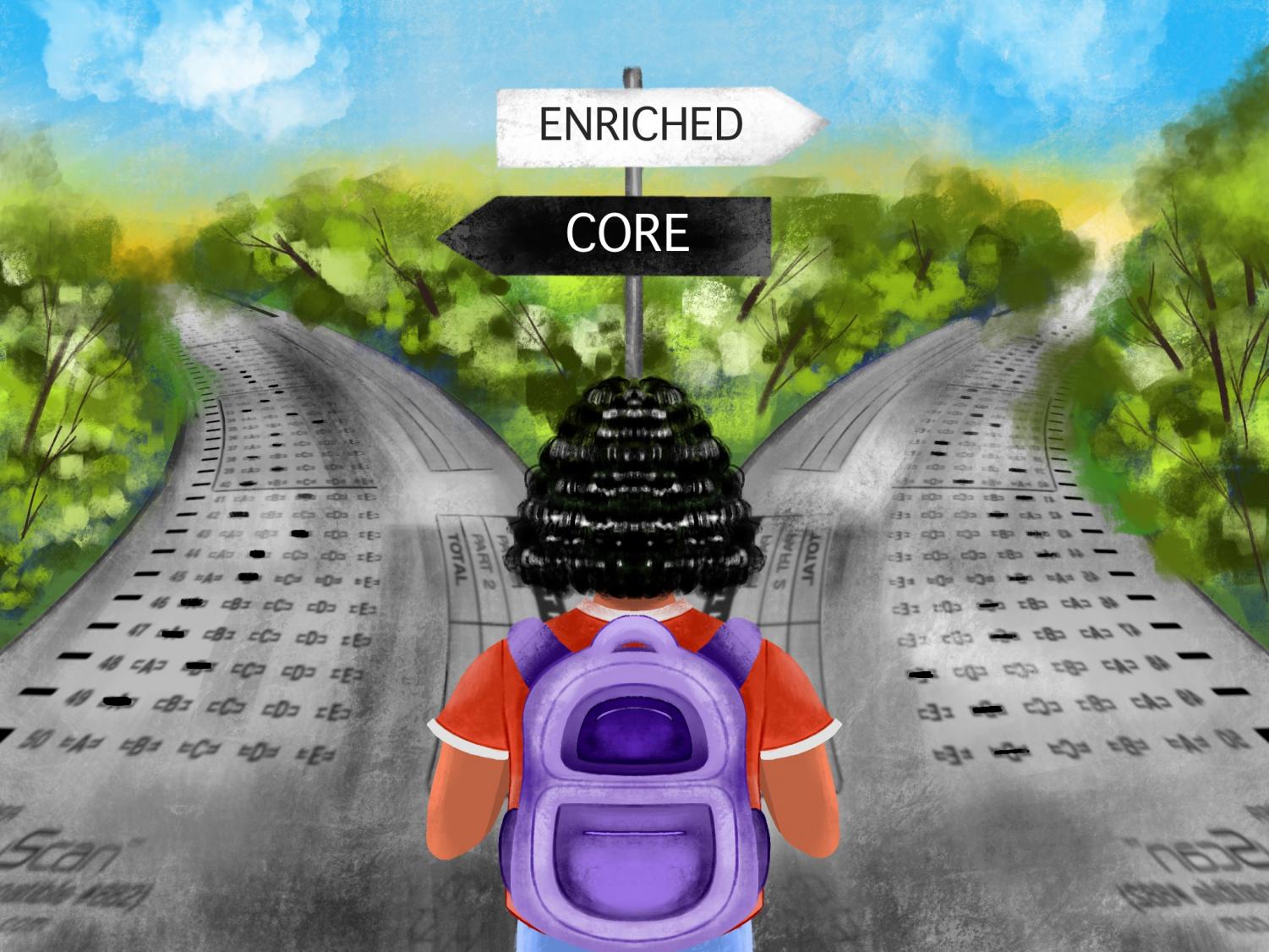

When I was in fifth grade, I was not in Enriched Math 5. I was just in Math 5. I noticed a difference between students in my class and the higher-level class: our skin colors. My lower-level class comprised black and minority students, while nearly all of the white students were in the enriched-level class. Today, 66 years after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, Shaker classrooms still appear segregated.

Dr. David Glasner, superintendent, visited a district elementary school and saw a class that appeared very similar to my fifth grade math class. Glasner, along with a few colleagues, asked a black student what they thought of the classroom demographics. The student responded, “Well, all the white students are in the enriched class.”

Students from elementary to high school notice segregation in their classes, yet no one talks about how the classes became so divided in the first place. Students think separation is just the way it is.

But this segregation isn’t a pure coincidence. This segregation stems from an old, insidious practice called tracking.

Upon entering fifth grade, Shaker students encounter significant changes as they leave their elementary schools for Woodbury Elementary. They walk into a strange school and meet new people, navigate the hallways by themselves and learn to play musical instruments.

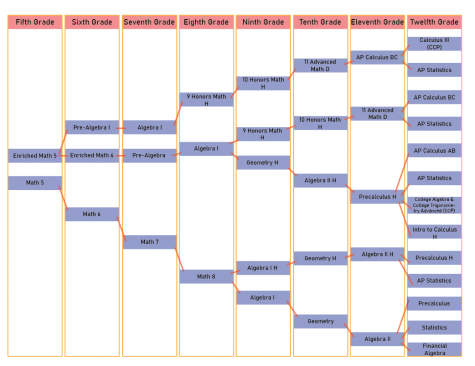

They are also placed on academic tracks that have the power to make or break their school careers; the classes they are assigned by fifth grade have the power to determine what classes they take through the rest of their Shaker educations.

Tracking is an educational practice that separates students into course levels and long-term paths. Tracks divide academic subjects into levels to which students are assigned based on their academic ability. The district recommends students to tracks according to a combination of teacher recommendations and standardized test scores. This separation begins in the fifth grade, and these academic tracks can create long-term paths for students.

In a 1988 New York Times opinion piece, Sandra Salmans wrote, “In one form or another, ability grouping has been in use in American schools since the late 1800’s. It was a response to the arrival of large numbers of ethnically and culturally diverse immigrants.”

Tracking was originally designed to ensure that students take classes that challenge them and have access to personalized instruction from teachers. It’s intended to allow students to learn at their own pace and level and reduce chances of falling behind or losing interest in a course.

A student completes an assignment with her Chromebook in an Onaway Elementary School classroom.

A less recognized part of tracking is ability grouping, a form of tracking within a class. It begins as students first learn to read and learn basic arithmetic but is most prominent in third and fourth grades.

For example, teachers divide students into groups according to reading skills. “In English class, there’s the high readers, the medium readers and the low readers. That can still be a form of tracking that isn’t discussed as much, but is just as much a part of the conversation,” Glasner said.

Dr. Erin Herbruck, director of primary education, said students are grouped based on their similar strengths and academic attributes. “They work together and grow together,” she said.

Students are placed in these groups after observations are made by teachers. According to Herbruck, teachers identify students in their classrooms who show enriched-level skills in those courses.

Then, teachers assign students to ability groups, considering the open-enrollment policy only applies to fifth grade and on. Ability grouping works by a push-in model, meaning enrichment teachers come into the classrooms in third and fourth grade instead of students leaving, as they did in the past. The enrichment teachers teach and support grade-level teachers with the whole class and small groups.

In theory, ability grouping in districts such as Shaker, one with a wide variety of academic strengths and weaknesses, is necessary and makes sense. It allows a teacher to focus instruction to meet students’ needs by working in smaller groups. But Herbruck said there is also a need for more heterogeneous groups that feature diversity in previous academic achievement as well as race and gender. Students can help one another grow and learn from one another’s mistakes. Yet, a concern with heterogeneous groups is the different instructional paces diverse students need.

Ability grouping can possibly set students back from the level of achievement they could eventually reach. Skills such as multiplication and division are introduced in third grade, skills that will never go away. They are the basis of every other math class, as well as the tests in a student’s future.

Teaching with ability groups sets up different levels of skill sets, expectations and motivation before students are placed onto tracks. Therefore, low-and average-level students deserve to face the same expectations and receive the same motivation as their enriched-level peers before they’re placed onto tracks.

From third to fifth grade, I was in the average-ability math group. I felt discouraged and lesser than my enriched-level peers. Despite performing at an enriched level by sixth grade, I always doubted my skills as I participated class with students who had already been on this track, and I still do. The message the district is sending to 9 year olds in lower ability groups can be demoralizing.

Senior Adaeze Okoye agrees that dividing students into ability groups in elementary school creates lasting, negative effects. “It seemed like there was this pedestal you were put on if you got to go to the high group, when I was in the third and fourth grade, instead of sitting in the normal class. And there’s students who think, ‘Oh I‘m not as smart as them, so I’m just not going to try anymore’ or ‘I don’t even care anymore and that mind set follows them into high school,” she said.

In addition to the long-term effects of ability grouping, the standardized tests Shaker relies on for tracking can harm minority students.

In fourth grade, students take the Measures of Academic Progress test in the beginning, middle and at the end of the year. According to shaker.org, “The program instantly analyzes the student’s response to each test question and, based on how well the student has answered all previous questions, selects a question of appropriate difficulty to display next.” The purpose of the test is to measure growth in performance over time, but the district uses it as a recommendation for class placement.

But the National Academies Press explains that standardized tests, such as the MAP in Shaker’s case, are used to measure a student’s ability to move forward. More importantly, they cause “profound implications for the development and future life chances of young people.”

Unfortunately, black and white students confront these tests with inequitable knowledge and experience. According to Brookings, a nonprofit public policy group, this inequity is considered the school readiness gap: the difference in school readiness between black and white students in terms of math, reading and behavior.

The school readiness gap is caused by differences in socioeconomic status. The American Psychological Association explains that a lower socioeconomic status early in childhood leads to a slower development of academic skills such as memory, cognitive development and language, due to a lack of resources.

In 2017, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, 15.7 percent of black families in Shaker were considered low socioeconomic status, while only four percent of white families were in that category. According to a 2018 ProPublica analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education, 41 percent of Shaker students receive free or reduced lunch.

This difference eventually leads to a racial disparity in class placement, as students of lower socioeconomic status continuously receive fewer opportunities and resources for learning.

A student’s performance and test scores in a course don’t go away as a student moves on to the next year, but begin to define the path they will follow. Due to the school readiness gap, students of color usually don’t get the same access to education and opportunities as their higher-performing and, typically, white peers.

Some 10 year olds recognize course levels and the way they correlate with skin color, and the district understands the future impact of the MAP tests. But not all 10 year olds grasp how the standardized test they are taking today can affect the rest of their high school educations.

As students head into fifth grade, they receive mail about course level recommendations.

Students and their families are informed of placement guidelines, considerations for enriched courses and where they are recommended to be placed. These recommendations are based on their performance in the course in fourth grade as well as test scores. For example, a student recommended for Enriched Math 5 may have scored 233 on the MAP math test, 218 on the MAP reading test and performed well in fourth grade.

These recommendations are not permanent placements. The district has employed an open enrollment policy since at least 1985. Although Shaker has followed the policy for more than 30 years, Guidance Department Chairman David Peterjohn said that it has been more publicized in the last five to six years. This policy allows families from fifth grade on to place their students where they want and feel they are the best fit, regardless of the school’s recommendation.

“Nothing can keep a student out of a course if a parent just says, ‘This is what I want for my child,’ ” Woodbury Principal Danny Young said.

After these decisions are made, students build knowledge and skills that will carry onto the next year. According to the 2017-2019 Academic Planning Guide, “Students are encouraged to pursue the highest level of instruction matching their motivation, interest, and previous learning.”

While the open enrollment policy gives students flexibility in courses they’re allowed to take, we need to recognize that what a student learns and masters one year follows them to the next. This starts as early as third grade, when ability grouping begins.

Open enrollment would seem to mitigate the ongoing effects of tracking. But, there are de facto prerequisites for some courses. The district does not use the term prerequisite, but according to Peterjohn, “There’s certain classes you have to take to have the foundations for others.”

“We aren’t going to turn people away from taking other classes, but obviously you have to do Algebra 1 and Algebra 2 before you do Pre-calc,” Peterjohn said.

Despite our district’s open enrollment policy, the longer you are on a track, the harder it is to break away from it and take advantage of this policy. Therefore, it’s important for families to be involved in their children’s educations before it’s too late. It is not a fourth grader’s place to understand the long-term importance of tests and placement. This means a student’s family and background are just as much of a part of their education as is the student.

According to the APA, parents of lower socioeconomic status can struggle to balance the roles that come along with family and work, and thus may be less involved in their children’s educations. These families tend to be less familiar and comfortable with the district and their amount of control over their student’s education.

Parents must do more than motivate and set expectations for their children. The ability to understand the way our district works is crucial. But not all families have the time to develop or acquire the skills and relationships necessary to understand our district. With time and resources, such as parent relationships, teacher relationships, or experience in navigating school systems, parents can understand how to use the district to their child’s advantage.

Considering the disproportionate effect of tracking on minority students, it’s important that parents of all demographics and the administration work together to guarantee that Shaker students are getting the best education possible. Students who lack support as they progress through the district can accumulate negative effects in course placement and academic performance.

The administration and community have acknowledged disparities brought about by tracking through programs such as the Family and Community Engagement Office and CommUnity Builders. While these programs bring up the discussion of the inequities in our district, that’s not enough.

It’s time to start implementing solutions and not just talking about them.

Public schools around the nation are dropping their tracking systems to work toward long-term, equal achievement between black and white students. In 2002, school districts such as Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland began to detrack their systems. This district eliminated its lower and advanced tracks to create diverse classrooms with mixed levels of achievement.

The Montgomery County Public School system comprises students of similar demographics to Shaker’s. In 2002, minority students made up 51 percent of the Montgomery district. These students face the same barriers and feelings minority students in Shaker feel. The Montgomery County Education Forum explains the need for detracking as a way to address the fact that their county afforded “upper- and middle-class white and Asian children a better education than African American, Latino, Native American, special educ

The tracks students follow are determined by their previous learning. A track can prepare a student for some future classes, but not for others.

ation, and less economically advantaged children.” It wasn’t even two years later, however, when they had to address the inequitable education minorities receive again. So, while detracking was a great step toward inclusivity and diversity in classes, it is still not a complete solution.

I do not believe that students in Shaker would thrive without the range of course levels to choose from. It makes sense for Shaker to keep the option of letting families and students pick a pace that works for them. But if the tracking system remains, more effective measures need to be taken to prepare black students equally.

The education a child receives as young as 3 or 4 years old will be more impactful than any program Shaker currently has to offer. We can achieve a more equitable education through universal preschool.

Offering pre-kindergarten education to Shaker families who otherwise would not have it would start to close the school readiness gap, or at least lessen its hindering effects. Universal public preschool would provide minority students with the earlier exposure to the knowledge and skills they will eventually be tested on.

The district currently offers preschool at Onaway and Mercer elementary schools, which each accommodate 16 students, according to shaker.org. While the Fernway fire was a tragic event for this community, it doesn’t have to be. The elementary school building could be used as a preschool. If Shaker had the opportunity to provide universal preschool, students could develop the emotional, social and academic skills that form the foundation needed to excel from kindergarten and on.

Of course, there is no telling when Shaker will be capable of offering universal public preschool — if ever. It would be expensive and require extensive planning that I don’t see possible in the near future.

Realistically, we cannot fix the inequities caused by tracking, but instead ameliorate them.

Instead of long-term actions, we should focus on what we as students and a community can handle. Smaller actions that can create change without years of planning are the best way to approach inequity brought about by tracking.

There are actions our parents and community members can take, but it would require participation from parents across races and socioeconomic statuses. We cannot expect much change to come if black and white families aren’t collaborating. Shaker parents need to break the boundaries within the Shaker bubble and strive for the common goal of unity and equity. They should also want all parents to be included and have the same experience in our district.

Having more parents form new relationships across communities will have a positive effect on the district. I have watched my parents help other black families get involved and understand our district, as other parents did for them in the past. If more parents worked to amend the disproportionate amount of black families compared to white families involved in our community programs, such as the school board or PTO, we would be closer to the goal of equitable education. It’s as easy as reaching out of our comfort zone and forming an informal network across the diverse communities in Shaker.

The same goes for us as students. We need to reach out of our comfort zones in and outside of class.

It is now five years after my first observation of almost segregated classes, and I sit in higher level classes. I see the same differences between the demographics of the higher-and lower-level classes, but I notice other things as well. It’s not just race that creates differences in a class, it’s the experiences that black students face, too.

The experience that a black student faces in Shaker is at times uneasy and challenging for reasons aside from the curriculum. I have heard black students discuss the isolation and awkward feeling of being one of the few students of their race in a class.

Black students recognize these differences more than their peers do, but they should not be the only ones who want to change this feeling.

Black and white students, along with their parents, need to reach out to each other. We should all want everyone to succeed and achieve as best they can. Smaller actions will be a great step toward breaking social barriers that divide minority and white students. Actions as small as white students including more black students in their group chats or study groups.

It could also be as small as more black students leading by example and breaking the uncomfortable social barriers that keep other black students from wanting to participate in honors or advanced classes.Imagine the progress we would see in our district if students, staff, administration and parents acted on the goal of equity in education.

Black students make up 52 percent of the high school student body and 46 percent of the district enrollment, yet they do not receive the same Shaker experience as their white peers.

We, as a district and community, know and talk about this. We need to do more, because if we continue the same efforts we have always made, the results will be the same.

It’s time to change the methods by which we approach these inequities, instead of continuing to let our students of color experience a separate education.

If we are successful, maybe it won’t take another 66 years to integrate Shaker classes.

A version of this article appears in print on pages 32-39 of Volume 90, Issue I, published Dec. 9, 2019.