Invest in Restoration, or Abandon It

Restorative practices have the potential to improve the Shaker community

August 26, 2019

Restorative practices. Over the past few years, it’s a phrase we’ve been hearing a lot around Shaker. It began with my class at the middle school in 2015. Since then, it has been the subject of persistent conversation throughout the district. But in the four years since restorative practices appeared in my life, the effect has been limited.

My first experience with Shaker’s version of restorative practices occurred in my eighth grade history class. One student caused a conflict with a classmate, and a few weeks later, we held a harm circle to discuss what had happened. By the time we got around to convening the circle, the class was had almost forgotten the incident, and the restorative practices were ineffective. While the same problem between those two students never occurred again, there was no real healing and no real closure for the victim. But I believe restorative practices can be much more effective when implemented correctly.

The purpose of restorative practices is to repair, rather than punish. From altercations between students to excessive tardies, these behaviors would launch efforts to discover the root of the problems, rather than just disciplining students.

Restorative practices are meant to strengthen relationships between individuals and within communities. A correct implementation of restorative practices would benefit students. If students and teachers could better understand and trust one another, the school environment would be both healthier and happier.

After speaking to Gabriella Celeste, a Shaker resident and expert on restorative practices, I learned how restorative practices could begin to solve inequity problems at Shaker. She said that while restorative practices are a good first step, “My sense is that in order to tackle equity, like in the disproportionate use of out of school suspensions, schools have to adopt an explicit racial equity approach.”

“Restorative practices come down to building authentic relationships. It’s not about a single approach, but a whole culture shift in how we engage with each other. And right now our district is in need of serious trust-building between students, staff and the community. Restorative practices could help us get there, but it has to be done right,” she continued.

This is why restorative practices are so important.

A March 1 letter written to the administration and signed by 12 parents requested that the district begin implementing restorative practices at the high school. The parents asked that the school invest the resources necessary to effectively begin using restorative practices and that it make a clear plan, using lessons learned at the middle school to help make decisions.

One person at the center of this push for restorative practices is our next superintendent, Dr. David Glasner. He was principal at the middle school when I was there and he led the implementation of restorative practices at that time. In an interview, he told me that there is both quantifiable and anecdotal evidence proving that restorative practices have been successful in the middle school. He’s talking about suspension rates, which have decreased. But there is still uncertainty about whether behavior is changing for the better.

In the March 18 Shaker Heights Teachers’ Association newsletter, eighth grade history teacher Michael Sears wrote, “In recent weeks, there have been an alarming number of student fights where staff members are seriously injured.” Sears also wrote the principal of the middle school, Miata Hunter, had to call an assembly to remind students of behavioral expectations. In the same newsletter, seventh grade English teacher John Koppitch cited instances in which teachers have been injured while attempting to break up fights.

So, it is important that these practices begin falling into place correctly. After talking to Lisa Vahey, an advocate for restorative practices in Shaker, I learned that low-level training has occurred in Shaker, but not enough to make a real impact.

Shaker has two choices: Invest heavily in restorative practices, or abandon them. Simply not suspending students and calling the statistical results proof that restorative practices are a success won’t work. If the district wants results — and credit for their use of restorative practices — they must put in the time and money to ensure it works properly.

I’d argue that the solution at the middle school is not to revert to previous ways of punishment, but to provide more training and resources to teachers, to make that investment.

Middle school science teacher Christopher Oryl told me that fostering a community in the classroom is difficult to do in a short period of time without a consistent framework. He’s in favor of restorative practices and he thinks community circles are helpful, but he wishes they didn’t cut into his class time. This is a complaint echoed by teachers across the district: Restorative practices are good, but restorative practices without funding and effort can create an unsafe and unproductive learning environment.

Restorative practices will help sustain the community we’ve worked so hard to build only if we implement them the right way. A good example of this is the work done in California’s Oakland Unified School District, which has become a model for instituting and supporting the approach.

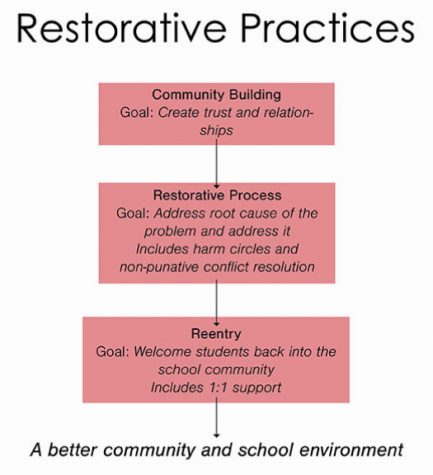

In OUSD, there is a three-tier plan for restorative practices. It begins with building community, which includes classroom circles and aims to create trust and relationships. This is followed by restorative processes, which include harm circles and other non-punitive conflict resolution strategies. The goal of the second stage is to find the root cause of the problem and address it. Finally, OUSD utilizes an individualized re-entry program which helps to welcome students after they have been removed from the school environment for disciplinary reasons.

In addition, according to a Feb. 12 Edusource story, OUSD employs five restorative justice coordinators and about 24 facilitators, who work in district schools and “are responsible for all restorative justice efforts at the school sites.” The five coordinators “manage the facilitators and train teachers and students in restorative justice techniques.”

OUSD serves approximately 49,000 students and spends about $2.5 million on restorative practice annually. (Protests have followed a proposed cut of $850,000 in the OUSD restorative justice budget, however.) Shaker is a district of 5,000 students. By rough estimate, the cost for a similar program would amount to about $260,000 a year.

A well-conceived and staffed approach such as OUSD’s has the potential to change the game at Shaker, so long as adequate resources are devoted to it.

Restorative practices aren’t only about changing the way we implement discipline, but the growth of our students as human beings. Our community is worth this investment.

A version of this article appears in print on page 54-57 of Volume 89, Issue II, published April 26, 2019.