Banned Books and You

Intellectual freedom matters

May 25, 2022

As visitors entered the 1982 American Booksellers Association Trade Exhibit and Convention, they were greeted by five-hundred books contained between a few large padlocked metal cages. A sign overhead warned them that some people considered these books dangerous enough to ban them.

This exhibit was a success, and prompted the American Booksellers Association, the Office for Intellectual Freedom and the National Association of College Stores to create Banned Books Week, an annual tradition dedicated to the celebration of intellectual freedom. Every year at the end of September, bookstores and libraries across the country promote, sell and host readings of banned books.

Throughout US history, book censorship has been a common mechanism to restrict the flow of ideas and information. Indispensable classics and great books have been barred from shelves, including Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Angie Thomas’ “The Hate U Give,” Susan Kuklin’s “Beyond Magenta,” John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men” and many more. The point of reading and promoting banned books is to show the worth they have as introductions to new perspectives and ideas. By picking up a banned book, you’ll not only learn more about the subject at hand, but you’ll also gain insight into the agendas of those who banned the book.

Not all book censorship is explicitly political. The ALA reports that the most common reasons cited for challenging books is that they are sexually explicit, contain offensive language or are unsuited for any age group. However, these complaints and ones like them are often masked political actions; it is common to see a book involving otherwise controversial (for lack of a better term) characters or events called out for these reasons.

Thirty-two percent of book challenges come from parents, who are often participating in organized movements. For instance, No Left Turn in Education offers examples of challenge letters and petitions for parents to imitate.

A larger trend has emerged through the past few years: justifying censorship on the grounds of getting rid of Critical Race Theory. Critical Race Theory, as an actual theory held and discussed in academic circles, primarily arose in legal circles, and holds two main tenets: that race is a socially constructed categorization, and that racism can be embedded in legal systems and policies. However, the word has become something of a catch-all in political usage for anything identifying racism with systems and groups rather than wholly with isolated individual actions. ‘Critical Race Theory’ is now so vague of a term that it has now apparently been spotted in math textbooks.

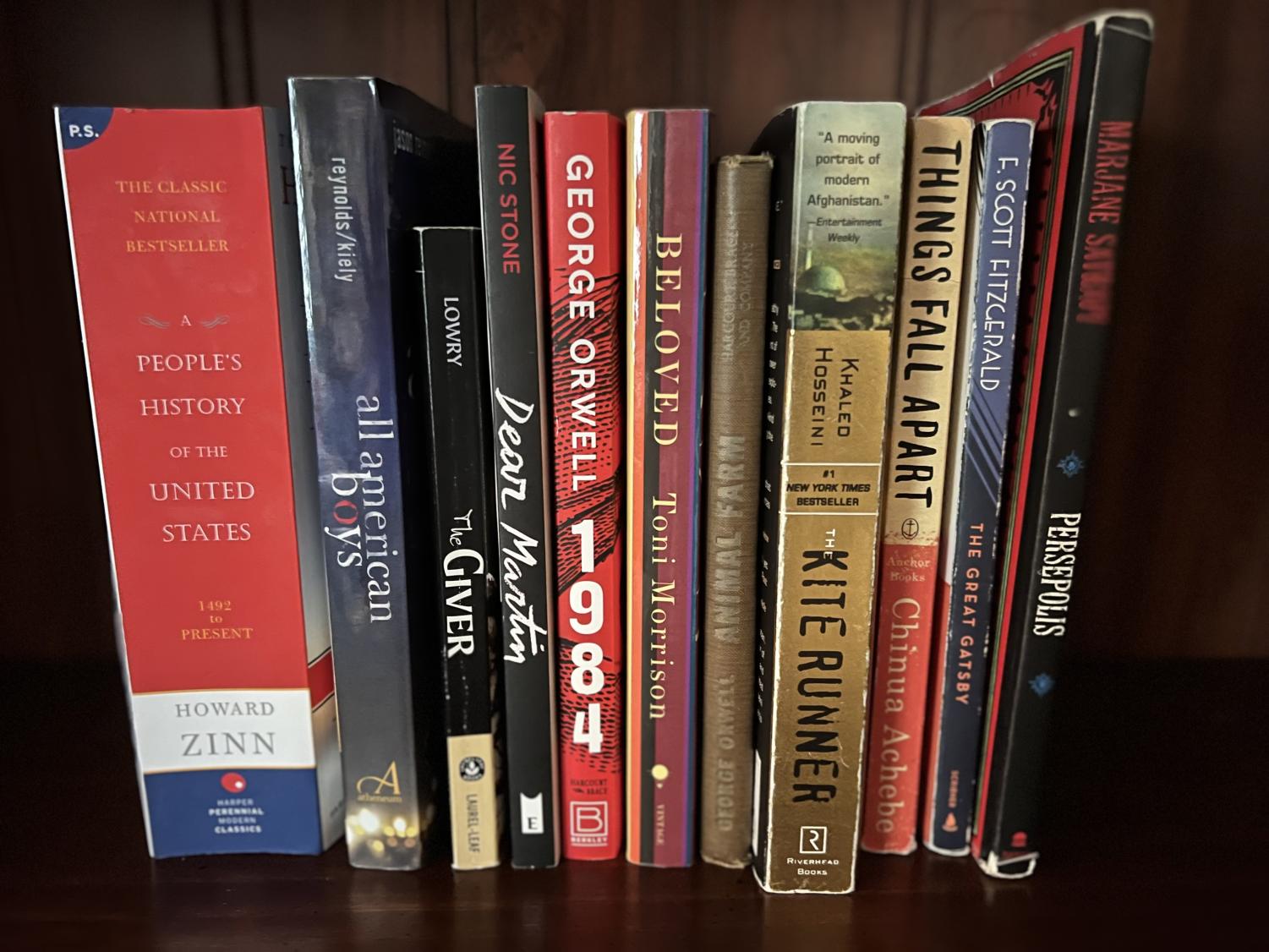

Frankly speaking, Critical Race Theory is more often than not used simply as a term to justify otherwise motivated political goals: the normalization of censorship, the need to protect the US from any justified criticism and so on. Under the guise of eliminating CRT, numerous books discussing or even mentioning antiracism, police discrimination, white supremacy and the ability of public institutions to propagate racism have been challenged or banned, including: “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “All American Boys,” “The Confessions of Nat Turner,” “A People’s History of the United States” and “The Hate U Give.”

Ohio House Bills 322 and 327 are part of the nationwide political protest against Critical Race Theory. The House Bills, currently sitting dormant in the Ohio State Legislature, seek to eliminate the teaching and discussion of certain concepts relating to race and bias, such as unconscious bias. This includes the use of certain books in curricula and their addition to library collections. There are a number of other things the bills seek to restrict or eliminate as well, including the awarding of credit for attempting to influence public policy. This particular clause will, of course, eliminate numerous fruitful projects in current curriculum, and the elimination of these would discourage political activism among younger generations. The bills were originally introduced in June, 2021 and were up for discussion in September of 2021.

These bills threaten to undermine Shaker’s track record of being mostly book-censorship free. According to high school librarian Robin Sweigart, the high school hasn’t banned books in the five years she’s been here. However, some books Shaker teaches in Language and Literature classes, such as The House of the Spirits and The Bible/As In Literature, have been challenged by parents, according to Language and Literature Department Chair Emily Shrestha. Alternative resources and activities are available for students who don’t want to or whose parents don’t want them to participate in the units involving these books and topics. No recent attempt to challenge a book being taught has gone as far as to try to remove it from the school’s curriculum, according to Shrestha.

Both Needham and Shrestha said that they would be very hesitant to police what students are reading. “I am, as probably most of my colleagues are, vehemently against censoring books and censoring thought,” Language and Literature teacher Nalin Needham said. Shrestha additionally expressed hope about Shaker continuing to resist censorship in light of last year’s House Bills – Shaker has been vocal in the past about opposing other bills that could be detrimental to schools if implemented, “My hope is that we would continue to reflect that,” she said.

Shaker students are also skeptical of heavy book censorship. “All books or points of view should be out there and displayed equally for people to see,” freshman Naran Khoury said. Junior Christopher Waters noted that even if books were banned, students would still be able to access those books on their own. “It’s better to learn in a controlled environment,” he said.

Cleveland Public Library doesn’t ban books, according to Cleveland Public Librarian Erica Marks; “If we had to really ban books because of everybody’s opinions and their concerns, we would be doing a disservice to a lot of young people,” she said. If parents call the library and ask for a book to be removed, librarians usually recommend them to accompany their child during visits to the library instead of trying to restrict everyone’s access to a book. The library also participates in Banned Books Week every year. Banned Books Week is celebrated at Shaker Heights High School Library as well.

Local independent bookstores additionally celebrate intellectual freedom and avoid book censorship. Mac’s Backs on Coventry hosts a large variety of new and used texts, including classics, new releases, obscure but nevertheless great reads, books by local authors and most importantly, banned books. Mac’s Backs celebrates Banned Books Week not only with the display and promotion banned books, but also with engagement with visitors on the issue of book censorship.

The bookstore’s selection corresponds with Mac’s Backs owner Suzanne DeGaetano’s emphasis on disseminating new perspectives and ideas. “A collection’s goal is to have a broad range of choices for everyone. What one parent deems inappropriate, another may deem essential,” DeGaetano said. “I don’t think kids and teens need to be protected from ideas, I think they need to be exposed to ideas. They will make their own value judgments and learn and grow from the reading experience.”

Shaker’s High School Library, as well as Cleveland Public Library, are meant to curate a wide variety of perspectives and literature, according to librarians from both. Librarians tasked with choosing the books for the shelves know what they’re doing. “In order to become a librarian, you take classes, graduate-level classes, and we’re taught about book selection and given tools to use in order to make the best decisions, and then a lot of librarians, we use those tools – there are journals that have book reviews, there are places online that give book reviews – that we look at, that we use to take into consideration,” Sweigart said. Librarians and teachers are careful to select materials and provide context for students. Hence, there is no reason to worry about creators of curriculum purposefully disseminating misinformation.

We’ve come a long way since the first recorded case of book censorship in what was to become the United States. No longer are books banned for being “fraught with profane calumnies” against the “good and chief men of the country” and “the ways of God.” Nevertheless, book censorship is a political vehicle in the modern social climate. “We shouldn’t be afraid of books, we shouldn’t be afraid of characters and we shouldn’t be afraid of ideas that are different than what we think,” Shrestha said.

So this September, visit a local bookstore or library and help celebrate the tradition of honoring banned literature that started all those years ago with a few padlocked metal cages full of books and a sign.