We Are Shaker

The district employs more Black teachers than the national average, but faculty don’t reflect student diversity

July 26, 2020

Editor’s Note: This story has been revised to correct the statement that no Black faculty teach AP or IB classes at the high school. Mario Clopton-Zymler, who is Black, teaches the IB Diploma Programme Music course.

Picture this: A white teacher instructing a class of majority Black students.

This is not an unusual sight in the district, which comprises nearly 50 percent Black students. However, this image becomes especially poignant when it represents African American History classes at the high school.

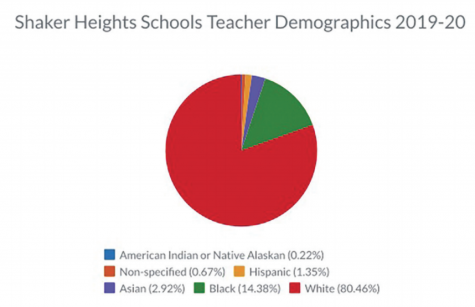

The district’s student body reflects a minority majority: 45 percent Black, 41 percent white, 5 percent multiracial, 3 percent Native American/Alaskan, 3 percent Latino and 3 percent Asian. And its teaching staff is 80 percent white, 14.4 percent black, 3 percent Asian and less than 1 percent Native American/Alaskan or non-specified. Although the district employs more than double the amount of Black teachers as the 7 percent national average, that number falls far short of reflecting the diversity of the student body.

The lack of faculty diversity is not an issue unique to Shaker. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, during the 2015-16 school year, 80 percent of U.S. public school teachers were white. Nine percent were Latino, 7 percent were black, 2 percent were Asian, 1 percent were multiracial and less than 1 percent were Native American/Alaskan.

Senior Kennedy Fletcher said she has not had any black teachers throughout high school. “It’s really easy to notice when people don’t look like you, and you take all this instruction from them,” she said.

The lack of diversity among both students and teachers in honors and Advanced Placement classes is also discouraging, Fletcher said. “What do I do? Who do I go to for guidance? Especially because I know the journey is going to be different for me than it was for somebody who doesn’t look like me,” she said.

Sophomore Journee Byrd-Allen said she shares a similar experience. “It kind of makes me feel like an outlier because I take advanced courses and honors courses, and there’s not many Black teachers there,” she said. “So it’s not like I can really get comfortable or maybe go to somebody that would understand me more as a Black student.” Mario Clopton-Zymler is the only black teacher in the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme; he teaches a Music course. This absence is not unique to AP and IB classes; only 11 percent of the district’s high school teachers are Black, while 85 percent are white. Three percent are Asian and 1 percent are Latino.

Math teacher Angela Harrell wrote in an email that each year teachers are asked which classes they prefer to instruct, and she has never witnessed a Black teacher denied when asking to teach AP or IB classes. Harrell said she cannot speak for all Black teachers, but explained that she teaches Algebra 1 Honors to encourage all her students, but her Black students in particular, to pursue higher level classes.

“So many students come into my class believing they are not good at math,” she wrote. “It is a mission of mine every year to change the student’s mindset; I want them to leave me at the end of the year knowing they can be successful in math.”

Last spring, SHHS graduate Jeremiah Caver (’19) told The Shakerite that teachers had spoken to him in a “simple-minded” way. “They talk to you like you won’t understand the way they talk to the rest of the class,” he said then, adding that he noticed teachers quickly relating information to his white friends but explaining it slowly to him, as if he wouldn’t be able to understand it otherwise.

Byrd-Allen said she felt discouraged when a teacher used this same style when speaking with her last year. “I am in the same class [as the white students] and I understand the same material as them, so I kind of feel judged there,” she said. For this reason, Byrd-Allen considered dropping the class. “I didn’t know if I could really handle the struggle of being judged and being the only black girl in there,” she said.

Harrell said teachers need to be taught how to make students feel like they belong in their class. “Conversations need to be had with teachers saying what they can do to make students more comfortable,” she said. It is also important to encourage students to take a class even if they’re the only minority student, Harrell explained. “Talk to students and tell them that they belong and shouldn’t think they don’t belong just because there aren’t other students that look like them,” she said.

African American history teacher Victoria Berndt, who is white, said she invites her students to discuss if it is inappropriate to have a white teacher teach African American history. “The overwhelming synopsis is that as long as the kids are being taught the history openly and honestly, they feel as though they can still get a good education from it; that it shouldn’t necessarily be based on race,” she said. Berndt said she addresses this topic because she lacks the perspective and experiences of a Black person. “Although I’ve had teachers who are African American in my bachelor’s program, I am still lacking a big perspective, and that’s not something that I pretend to even have,” she said.

Berndt also encourages her students to share personal experiences that she will not share outside the classroom without permission. “That’s how I try to make up for not having that background and that perspective,” she said.

There should be more Black history teachers in the district, especially for African American history classes, junior Shatara Dowdell said. “If it was taught by an African American person, I think it would’ve been different, like telling more stories about their lives,” she said. “I think I could’ve learned more about my background because I’m African American.”

One student who requested anonymity to protect the identity of their teacher, said they felt uncomfortable as the only Black student in a class when others looked at them with pity while discussing segregation and integration. The class was taught by a white teacher. “I think if my teacher was Black, [they] probably would’ve come up to me and actually checked on me to see how I was doing in the class or come up to me after school and ask if I’m OK during this subject,” the student said.

The disconnect between students and teachers of different cultures can result in microaggressions that discourage students from excelling in school, senior Adaeze Okoye said. She defined microaggressions as “intentional or unintentional insults, prejudice or derogatory terms.”

Microaggressions can lurk in compliments, Caver told the Shakerite last spring. When people offer praise by saying, “You’re so articulate,” the statement implies that the person who made that comment doesn’t expect him to be.

Senior Aaliyah Williams said some teachers or coaches speak to her in a “fake blaccent.”

“One time I was talking to a coach and [they] were like, ‘Hey, girl, wassup.’ It was a mix between southern and — I can’t even describe it,” she said. “It’s really weird because you know that’s not how they talk.”

Williams also said teachers sometimes comment on how often she changes her hair style. “ It feels like they’re treating me as if I’m something to be marvelled at, rather than just a human being,” she said. “Something about it just always feels so dehumanizing when they’re acting like my hair is not a part of me, like it’s not an extension of myself.”

Williams said some teachers also try to abbreviate her name. “They ask me if they can call me anything but my name. One teacher wanted to call me Liyah, one teacher wanted to just call me Lee,” she said. “It just feels as if they’re trying to separate me from my Black girl identity, and that’s just not something that I would ever want.”

Math teacher Jayce Bailey said being one of few black teachers creates pressure to become a spokesperson for all black people. “Sometimes it feels like you’re the go-to person. If there’s anything concerning Black cultural issues, people may ask you like you’re the only voice, and it’s hard to be one person to represent an entire culture. That’s not fair at all,” Bailey said. “While my view may be shared by some in the black community, it can also be very different compared to other Black people,” he wrote in an email. “What I am trying to say is that, while I will give my stance on a topic, you cannot assume that my one stance represents the entire community.”

However, Bailey said it’s important for him to represent Black males positively. “I think that letting kids see that Black males can be leaders can help shape them going into adulthood. They won’t just be blind and listen to what the media is displaying because sometimes the news doesn’t show a lot of successes. It just shows negative things,” he said.

It is important for all students to have a diverse teaching staff, junior MAC Scholar Rudy Collins said. “I just think that it’s good to see — after the history of African Americans — their success and how they’ve come to be a part of the world and a part of the nation today,” he said.

The district needs a teaching staff that better reflects its student body, social studies teacher Brian Berger said. “I also think it could be inspiring for people of color to see teachers of color and to realize they themselves can be teachers,” he said. “I think it’s really good to see yourself in possible jobs and positions.”

Bailey’s story echoes this idea; he said he engaged with lots of black teachers, principals and coaches when he was growing up. “I had some great teachers in high school, so I wanted to give back, so that’s why I went into teaching,” he said.

Collins said he was influenced to pursue engineering by MAC Scholar alumni who returned to talk about their careers. “It helped me a lot because there were a lot of people who came in from the field of engineering, which is now why I’m taking engineering,” he said. “Being able to see their success throughout their college career and now their working career gives me that mentality that I could do that as well.” Collins said that no scholars who went on to become teachers have addressed the group. Founding adviser Hubert McIntyre wrote in an email that current scholars decide who will be invited to speak.

A study conducted in France during the 2015-2016 school year tested whether exposure to female scientists could influence high school girls’ view and pursuit of science professions. The scientists spoke to students about science-related careers and the lack of women in the field. “The program increased the probability of enrolling in a STEM undergraduate program in 2016/17 by 2.4 percentage points, which corresponds to an 8.3 percent increase from the baseline of 28.9 percent,” the study states. Female students involved in the program were 10 percent more likely to enroll in selective STEM programs.

Would Black teacher guest speakers help influence Black students to become teachers?

Junior MAC Scholars Dalton Mosely and Evan Ward said they think so. Having Black teachers speak to the scholars may cause them to think, “He’s Black, he did that. I’m black, I can do that, too,” Mosely said. Ward said that it is beneficial to hear from alumni in any profession who have also gone through the scholars program. “When someone comes to talk to you that went through the same process as you, it shows [scholars] that they can do the same thing,” he said.

“I feel like young students seeing people that look like us would help them think that they can also aspire to be like that,” Mosely said.

Shaker alumna Angela Chapman (’81) attended North Carolina A&T State University, one of 107 historically black colleges and universities in the United States. HBCUs were founded in the early 1800s to ensure that all students had access to higher education. Chapman said the A&T was different from any other school she attended; most of her teachers were Black.

“My professors and adviser cared for me like family, and they were very concerned about my success, and about my well-being in general, not just academics,” she said.

Chapman said one of her professors visited her while she attended law school at Florida A&M University, another HBCU, to check on her and regularly kept in touch. One of her law professors also donated money to her family during a personal emergency in her second year of law school. “It was such a blessing, especially at such a crucial, highly stressful time,” she wrote in a text message. “That kind of support got me through undergrad and law school, and I will be forever grateful.”

Ayesha Bell Hardaway, vice president of the Board of Education and parent of Shaker students, said that having Black teachers was encouraging. She describes one of her Black law professors at Case Western Reserve University as “an amazing educator, very interested and engaged in my trajectory for success.

“I remember him saying to my kids at graduation that I could be whatever I wanted to be,” she said. Hardaway said she did not have this level of connection with her other law professors.

Hardaway is now a law professor at her alma mater. “I decided to teach at the law school to ensure that historically marginalized students would have the opportunity to work with a professor from a similar demographic,” she wrote in an email. Last year, she said, the majority of her law students were Black.

“I have heard from my Black students that they appreciate my teaching style and they appreciate my commitment to holding them accountable, setting high expectations and helping them figure out how to meet those expectations through our time together in the course,” she said.

Despite attending Shaker schools since kindergarten, Fletcher has had Black teachers in third and eighth grade only. “Being in third grade and seeing someone who looked like me, teach me, really did help,” she said. It’s encouraging to have a same-race teacher because “representation is important,” Fletcher said. She also believes that the lack of diversity in teaching staff may deter minority students from becoming teachers.

Chapman said the lack of minority teachers sends the message to minority students that qualified teachers don’t look like them. “It may cause one to feel that they can’t teach others as an adult,” she said. “That, in itself, is problematic because that stretches beyond the classroom.”

Mosely said, “One of the main things that would be able to motivate aspiring black students, would be that there are people that look like us.”

Diverse instructors are important to all students, according to Shaker parent Lisa Vahey. “Sometimes, as white parents, we feel like we don’t have to think about it because it doesn’t matter. My kids have had teachers who look like them. But, as a parent who cares about equity, I actually care about my kids having teachers that don’t look like them,” Vahey said. “I am a stronger human being because of my relationships with the Black women I’ve met in Shaker who’ve helped me think about things from their perspective and not only my perspective.”

Vahey said these friendships have changed who she follows on Instagram, the way she acts in meetings, what she pays attention to in the hallways of the school and more. “The value of a diverse workforce, a diverse friendship group, a diverse curriculum, I believe makes us stronger,” she said. Diversity builds a community “that is kinder and restorative and understanding, a community that has mutual respect for differences and really cares for and about each other,” she said.

Mosely said a diverse teaching staff would benefit all students, no matter their race by “helping you be more racially exposed and helping you understand new people and their perspectives and their world views,” he said, “therefore making you a more well-rounded and more experienced person.”

In addition to the benefits of career role models and heightened awareness and understanding enabled by diverse faculty, there is evidence that Black students perform better academically in the long run when they learn from a same-race teacher early in their school careers. Seth Gershenson, an associate professor in the Department of Public Administration and Policy at American University, studied the long-term effects on Black students who have a Black teacher in elementary school. The study examined factors such as college enrollment rates, high school graduation and drop-out rates to determine the impacts.

According to the study, having at least one Black teacher in third through fifth grade reduced the Black student high school dropout rate by approximately 31 percent. The study also showed a 12.4 percent increase in low-income Black students’ plans to attend college, according to high school survey results, and a 10 percent higher probability of taking a college entrance exam such as the SAT or ACT for all Black students.

Gershenson said the first same-race teacher a student has creates the greatest impact. “Even having one Black teacher seemed to really increase the Black students’ outcomes,” he said in a phone interview. The main result of the study is that a same-race teacher, even early in elementary school, has an evident effect 20 years later on whether or not Black students enroll in college, which shows the importance of student exposure to teachers of the same race.

According to the district, Erica Merritt was hired in August as the district’s Interim Equity Partner to “lay groundwork for a diversity recruitment and retention plan to help ensure the district has diverse and well-qualified candidates for future vacancies.” In the meantime, Merritt has led group discussions open to community members such as “Let’s Get REAL About Race,” “Interrupting Racism” and “How to Be an Anti-Racist.”

Later, after consulting Superintendent David Glasner, Merritt’s focus shifted to educating district administrators. “When I started to talk to Glasner about doing some more intense work, one of the things we talked about was really concentrating on people who are working in the district. Not that working with the community hadn’t been important, but because the focus had been so outward,” she said. “We really wanted to make sure the folks who were working in the district had experienced the same content and had the same baseline of knowledge.”

The internal cohort, Leading Equity, evaluates the history of racism in the United States and how it may affect education. They also discuss intervention for race-related issues on “an internalized, interpersonal, institutional and a structural level,” Merritt said. “I think that it’s focused on leadership because it starts at the top. It’s important that the people who are in positions of leading the faculty and leading the district have knowledge, and I’m not saying that teachers don’t also need it, but it really has just been a matter of starting at the top.” She said Leading Equity was limited to principals, administrators, teachers in union leadership positions, IB Coordinators, CSI cohort members and teachers with roles beyond their classrooms.

Harrell said diversity and equity training can help change a teacher’s subconscious actions. “Most of the teachers I have as colleagues have their heart in the right place, so they may do something unintentionally,” she said. Training “makes you become aware of the things you’re not aware of.”

According to Chapman, it is difficult for any teacher to share a cultural understanding with a student of a different race without intentional diversity training. “It’s not anything against white teachers. It’s just that the teachers of color and the white teachers have simply lived in different worlds and really can’t be expected, without intentional training, to have that understanding,” she said.

Merritt said equity training for teachers is only part of the solution. “I do a lot of training, and I think that it has value, but I think that it also has to be supported by other things, so that’s where the policy and practice pieces become really important,” she said. “I think what we need to do is figure out ways to both help educators to interrupt habits that are leading to negative results and increase habits that are going to lead to positive results.” Merritt said that the district’s Equity Policy and Strategic Plan would reinforce training.

Bailey said low wages are one reason Black students are not becoming teachers. “Coming from a place where we didn’t always have a lot, and I was going to college, it was always, ‘Hey, why don’t you pick something for the money?’ And I know other people that did,” he said. “They picked jobs because they wanted to make a lot of money.”

Chapman also identified low salaries as a deterrent to becoming a teacher. “People that ordinarily would want to teach, that would have a passion for teaching, shy away from teaching because teachers, historically, don’t make any money,” she said. Chapman believes that teachers need to be paid more, but said there are other ways to attract minority candidates. The district should “get some of these graduate students fresh off of a master’s program, offer incentives to help pay their student loans, and get them to contract for three to five years,” she said.

In Illinois, a Teacher’s Loan Repayment Program awards up to $5,000 to students who choose to teach in low-income schools. This federal government also offers loan forgiveness programs for teachers who work in such schools, although there is increasing evidence that the government is not honoring it.

Dowdell said if the district were to help pay her student loans, she would consider returning to Shaker to teach. “If I see that they’re actually helping me with college, not just saying they will, then yes,” Dowdell said.

Williams said she considered becoming a teacher until she realized what teachers earn. According to the National Education Association, in the 2017-2018 school year, the average starting salary for a public school teacher in Ohio was $35,923, and the national average was $39,249.

“Being a teacher seems like it can be so grueling and so horrible because you’re being underpaid for working crazy hours and doing all this emotional labor for these students,” Williams said. “But if Shaker offered to pay off my student loans, I think that that would take such a burden off of me.”

“I think that going to college then coming back and helping to raise other people into the person that they’re meant to be — I would actually love to do that,” said Williams, who added that earning lots of money to be considered successful is ingrained in American culture, and she, too, has been affected by that norm.

The starting salary for a teacher with a bachelor’s degree in Shaker is $48,075, almost $9,000 more than the national average. Shaker teachers who work five years with no further education earn $57,690.

By comparison, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, an accountant earns an average annual wage of $79,520, an engineer earns $88,800, a registered nurse earns $77,460, a social worker earns $50,410, a journalist earns $62,400, and secondary teachers earn $65,850.

Glasner said the district may be able to help pay off student loans in the future, but he is not sure. “There would be a lot of planning and discussions that would have to take place in order to offer that,” he said. “We do currently offer tuition support when teachers and other faculty are already employed by Shaker and going back to get an additional degree, or going back to school for other reasons.”

Glasner said the district has been working on other ways to diversify its staff. “Our goal is to make sure that we have a diverse representation of teachers and other staff from all different backgrounds, experiences and racial groups because we know that is what helps all students succeed,” he said.

Shaker is a member of the Cleveland Area Minority Recruitment Association. According to its website, CAMERA’s purpose is to “develop coordinated recruitment and retention of qualified minority educators that will enable member agencies to diversify their faculty more effectively.” High school Assistant Principal Tiffany Joseph, recently named Woodbury principal, attended CAMERA’s job fair with the Canton City School District last year and planned to attend with Shaker this spring. “A part of it is not only to network for positions, but it’s also to provide minority candidates with an opportunity to talk to people who might not necessarily work in administration or [human resources] to find out hiring tips, what’s appropriate and what’s not appropriate to do in an upcoming interview,” Joseph said.

However, the job fair scheduled for April 21 was canceled due to the shelter-in-place order issued by Gov. Mike DeWine March 23.

Joseph did attend the Feb. 22 Northeast Ohio Diversity in Education Recruitment Event. The group, whose events aim to help districts hire teachers who reflect student diversity, focuses on the impact that adults have on a community when they share similar experiences with students in terms of race, culture, gender, sexual orientation, socio-economic status and religion.

The district was unable to attend the Northeast Ohio Teacher Education Day April 7, due to DeWine’s order. NOTED is an opportunity for teacher candidates to meet hiring officials from districts in Ohio.

“Not only were we trying to be more visible at events of such nature, but we [were] also thinking about the people that we bring to these events, not just administration, but teachers who actually service the kids because we want to get multiple opinions about the candidates that we bring into the district,” Joseph said. “So I definitely think that it is the start of something great in terms of improving diversity in our district and impacting it positively.”

According to Executive Director of Communications and Public Relations Scott Stephens, the district will attend virtual job fairs through Diversity in Education when positions become vacant. “We are also looking at internal candidates in order to encourage upward mobility and morale within the district,” he wrote in an email. The district also informed partnering colleges of their “intent to draw a more diverse student-teaching pool,” Stephens wrote. Interim Director of Human Resources Crystal Patrick said these colleges include, but are not limited to, Kent State University, John Carroll University, Walsh University, Cleveland State University, Akron University, Baldwin Wallace University, Ursuline College and Notre Dame College.

Earlier this year, Glasner started a Black Teacher Task Force that “centers on recruitment and retention of black teachers, and is open to black teachers and black paraprofessionals,” he said. “I think they will have a lot of good input and feedback based on their experiences, to help us do a better job of recruiting with diversity and equity in mind.”

According to Merritt, the group first met March 3 and will continue to meet virtually. According to Stephens, Merritt is also working with Human Resources to explore ways the task force can be involved in the hiring process this spring. In June, she moderated online candidate forums for the two finalists for a new district’s new executive director of diversity, equity and inclusion position.

Concerns about the number of Black teachers in public schools are not new, and it’s unknown how much the lack of diversity within the teaching ranks will affect students while school is disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Collins said, “If you’re going through something that a lot of African American families go through often, and your teacher knows about it and they have lived through it as well, it allows them to be put into your shoes and see what you’re going through.”