Suspending Students, and Learning

Suspensions, expulsions, which affect minority students disproportionately, may contribute to achievement gap

November 15, 2016

Louisa sat down at a desk in a quiet room. Her pencils lay in a line. Her books were arranged in a stack. Her peers were nowhere to be seen.

The week before, she had gone into school, waited until lunch, and pushed another girl into the window. Security guards immediately intervened. They sent her to the office with the threat of suspension, or even expulsion.

Her parents’ pleading left her with only a 10-day suspension.

Louisa’s anger quickly faded as anxiety set in. “Every day I thought about how my grades would go down,” she said, “and how this would affect me in school.” But she didn’t feel bad about her actions.

Discipline comes in many forms. There are detentions, where students stay after school as punishment. There are in-school suspensions, where students go to school but don’t attend their classes. There are out-of-school suspensions, which range from one to 10 days long. Finally, there are expulsions, which allow for the removal of students from school for 20 to 80 days, or until the end of the semester (with some exceptions).

For school officials, the defining feature of each of these disciplinary actions is the amount of time a student is away from instruction.

Fifty-one years ago, the Shaker Heights Board of Education wrote a district-wide philosophy of discipline.

“The goal of any disciplinary action or counseling is to aid the student in developing self-discipline,” states the first of four guidelines.

This summer, Shaker employed Greg Zannelli as dean of students to enforce part of that ideology. “My philosophy is to do what’s best for kids and give them the skills to make better choices,” he said.

His arrival accompanied new disciplinary procedures for the high school. Zannelli recalled a consensus among assistant principals and administrators for Saturday school, one noticeable addition.

“The last thing we want to do is suspend students, because they’ll miss instruction time,” Zannelli said. “The data shows that what we’re doing should bring down the number of suspensions.”

But Zannelli explained that Saturday school is an extension of after-school detention rather than an alternative to suspension. Students sent to Saturday school receive the punishment for detention-level behavior such as having too many tardies or talking back to a teacher. Students caught fighting or participating in another suspension-level offense will not be sent to Saturday school.

Zannelli believes that suspensions detract from the end goal of education. If students are at home, their teachers cannot provide instruction.

Economics teacher Bryan Elsaesser recognizes that problem, too. “The student who is suspended usually gets way behind,” he said. “It’s usually not the kid with the A’s and B’s,” he continued. “It’s usually the kids who are already struggling anyway, so it makes it really difficult to keep up to date with everything.”

On the first day of her suspension, Louisa’s father drove her to the Shaker Youth Center. Normally she gets a ride to school with her friends, but on that day, their destinations differed.

Her schoolwork had been ferried from the high school the day before. Tutors awaited her arrival. “They gave us materials and textbooks, and we went to work,” she said. But without instruction from her teachers, she quickly became lost.

“Tutors can help you,” Louisa said, “but how am I supposed to know what I need help on if I haven’t learned it yet?”

Director of Student Affairs Ouimet Smith said the district’s goal is to continue a student’s education. “However there comes a time when we have to stop that education,” he said. “We don’t want to do that.”

Erin Davies is the executive director of the Juvenile Justice Coalition of Ohio. The group advocates for children in Ohio’s courts. “The one thing we know,” she said, “is that out-of-school suspensions and expulsions are extremely ineffective.”

“Tiered responses are essential,” Davies continued. “Discipline in schools can be as light as a teacher reprimanding a student, all the way up to a student being expelled.” She believes that those actions should match the misdeeds of the student.

Dean of Students Greg Zannelli writes a tardy pass for a late student. Tardiness is a tier-one discipline offence punishable by detention or Saturday school. Tier one discipline also includes dress code and cell phone violations.

“There is a spectrum of discipline for students,” Smith said. Shaker implemented tiered responses following that spectrum. “Zannelli will be responsible for tier-one discipline such as dress code, cell phone and tardiness violations,” the district website states. Smith handles appeals for tier-two discipline — suspensions and expulsions.

Zannelli and Smith both mentioned Shaker’s restorative justice practices. Restorative justice aims to reconcile an offender with a community rather than pursuing purely punitive measures.

Instead of detracting from education by sending students home, restorative justice sends them to a therapist or a group sit-down where they can talk about what they did and how it affected their community.

In the discipline community, it is agreed that communication brings positive change. “Starting a meaningful dialogue between students and administrators is essential,” Davies said.

“It gives students an opportunity to have a voice and share where they’re coming from,” Smith said. “That dialogue is a good thing.”

But Shaker’s restorative justice efforts occur in addition to punishment rather than in lieu of it.

Louisa’s day at the youth center ended with an hour-long group conversation. Students pulled their chairs into a circle and talked about what they regretted and why they did what they did.

Sometimes they watched a movie about anything from anger management to drug use.

“They would either pick one or two people to talk about their experiences, then we just go around and say something that’s relatable to it and then we would just give each other advice,” she said. “I liked it. It was like a therapy session.” For her, it was the best part of a long day.

Restorative measures and measured responses are helping. In middle and high school classes in Ohio, there are 33 discipline occurrences per 100 students. At Shaker, that number is 14. However, a lack of suspensions and expulsions is not the only indicator of successful discipline efforts.

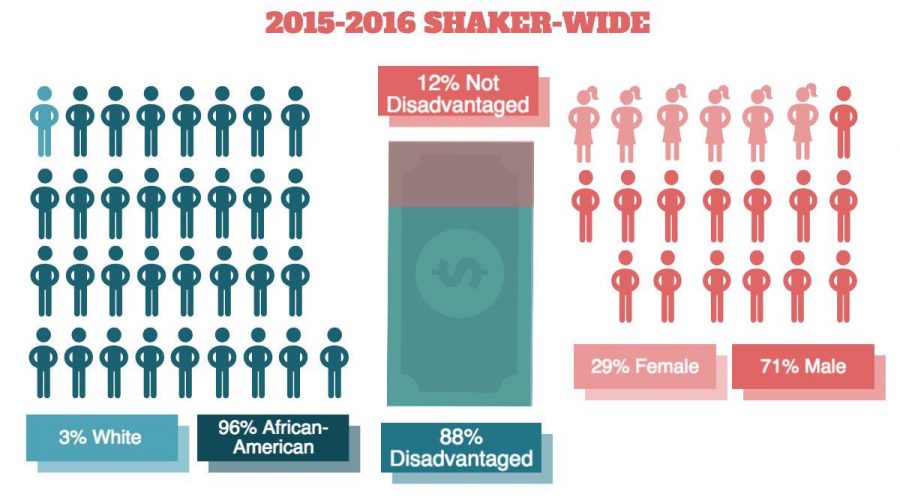

Equity is one of Shaker’s three main aspirations according to the district website. African-American students make up 51 percent of enrolled students; they account for 96 percent of the discipline. While white students make up 40 percent of enrolled students, they account for just 3 percent of discipline. Grace Loughleed

Grace Loughleed

“The numbers aren’t good, nationally,” Scott Stephens, director of communications, said.

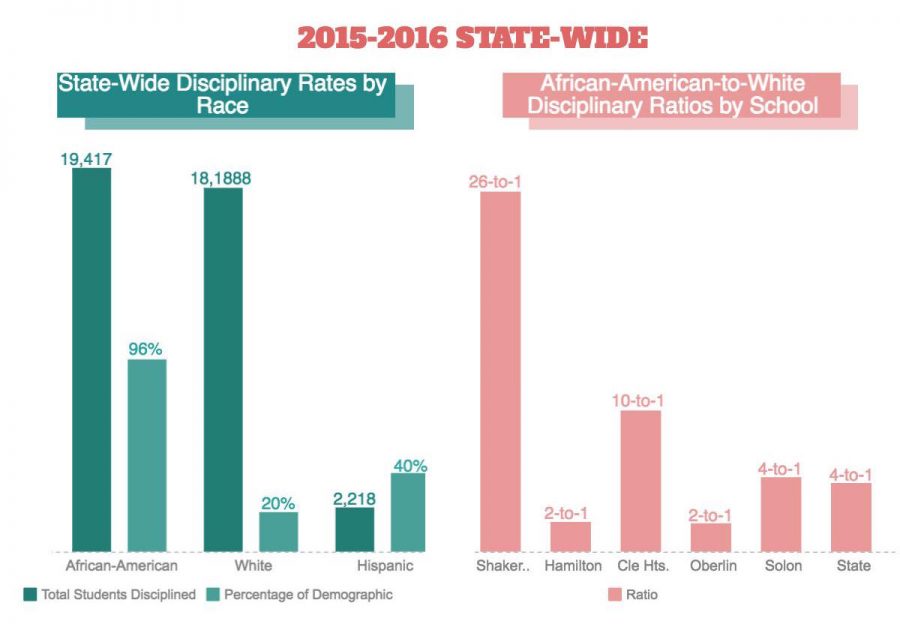

He is right. Although there are five times more white students than African-American students in Ohio public schools, the two groups are disciplined at nearly a 1-to-1 rate. When expressed as a percentage of the overall demographic, disciplined students thus represent a larger percentage of the African-American student population than the white student population.

If the same number of African-American and white students were disciplined one year, that number represents a five-times higher percentage of the African-American student population.

At Shaker, though, the percentage of the African-American student population disciplined is 26 times larger than the percentage of the white student population disciplined.

The district often points its unique features, from being diverse to being one of only eight districts nationwide to offer the International Baccalaureate program K-12.

Shaker is one of just 10 districts offering the IB Diploma Program in Northeast Ohio. But even in this selective group, Shaker is a disciplinary outlier. The Oberlin City Schools, another IB district, saw twice the amount of disciplinary actions in grades 7-12 as Shaker during 2015-16, but that discipline was more evenly distributed than Shaker’s. There, only two African-American students were punished for every single white one.

An imbalance doesn’t just arise when examining African-American versus white students. In Shaker, 278 African-American students are disciplined for each Hispanic student, and 16 for each multiracial student.

Shaker is also part of another, even more selective group. Twenty-eight schools across the nation comprise the Minority Student Achievement Network. These schools collaborate in research with the goal of closing the achievement gap between students of color and their white peers.

“MSAN districts have student populations between 3,000 and 33,000, and are most often well-established, first-ring suburbs or small- to mid-size cities,” their website states. “Additionally, the districts share a history of high academic achievement and connections to major research universities.”

In this group, Shaker is still an outlier. Cleveland Heights High School, another MSAN member, suspended or expelled a third more students than Shaker last year. But, like Oberlin, suspensions and expulsions occurred evenly across most demographics. Cleveland Heights’ ratio of African-American-to-white discipline is just 10 to one, nearly three times less than Shaker’s.

Hamilton Local Schools are in a suburb of Columbus. Its performance index — a measure of students’ performance on OAAs and OGTs — was 87.83. Shaker’s was 87.77.

Its achievement grade on the state report card was a C. So was Shaker’s. Like Shaker, its gap closing and K-3 literacy were both Fs. According to cleveland.com, it is the school most academically similar to Shaker.

But its discipline is far departed. Hamilton Local Schools saw a 2-to-1 ratio of African-American-to-white students disciplined. Grace Loughleed

Grace Loughleed

Shaker’s sub par performance on the state report card might stem from over-disciplining certain groups of students.

The West Virginia Board of Education spearheaded a study two years ago examining the “impact on student academic performance of referrals for disciplinary intervention.” They found a strong correlation between discipline referrals and failure in state math tests. Of students with zero discipline referrals, 42 percent scored not proficient.

After one referral, the number of non-proficient students reached 63 percent — with a 20 percent separation from those proficient. “This gap increased to about 33 percentage points when the incidents resulted in suspension,” they stated.

If African-American students make up the majority of those disciplined, the West Virginia Board of Education believes they’ll make up a majority of those non-proficient on state tests. At Shaker, this connection shows.

Shaker was given an F in the “Gap Closing” category of the state report card.

District wide, African-American students and students with economic disadvantages both scored 35 percent on the math state test. White-students scored on average 86 percent.

When discipline stratifies, so does performance. When gaps in discipline disappear, so do the gaps in performance. Solon City Schools demonstrate this correlation. Their ratio of African-American-to-white discipline was just five-to-one. Their African-American students scored 76 percent on the state math assessment; just 20 percent less than their white students. This success among all demographics increased their performance index to 110.59.

Solon also has 13 percent less discipline overall, another possible achievement factor.

“Every educator is aware of this,” Smith said. Shaker’s making steps to replicate it.

“Implicit bias training is really helpful,” Davies said. Implicit bias training is a part of cultural proficiency training which focuses on identifying “subtle cognitive processes” that impact how we view others, especially those of other races.

The Shaker Five-Year Strategic Plan details the implementation of cultural proficiency training over three years. A culturally proficient teacher recognizes students’ unique backgrounds and endeavors to relate with them. “It’s not walking a mile in their shoes so much as it is just taking a look around from their point of view,” Smith said.

The first year, 2014, was meant for training of principals, teachers and “leaders.” Last year was for faculty and staff. By the end of this school year, the goal was to have the entire community (including students and parents) culturally proficient to some degree.

“A lot of staff members go to the training,” Smith said. “Is it formally set up that they have to? Not necessarily. But they all have the opportunity.”

Davies believes these steps are in the right direction.

Whether students are male or female or economically disadvantaged also contributes to the likelihood of suspension and expulsion.

Males at Shaker are disciplined twice as often as females. Students in eighth grade are three times more likely to be disciplined than those in twelfth grade. Those with an economic disadvantage are disciplined eight times as often as those without.

In fact, behind race, economic disadvantage is the most impactful disadvantage there is, in terms of discipline. And in Shaker, economic disadvantage is abundant: 36 percent of students have an economic disadvantage, and African-American students make up more than half of them — Hispanic students make up another fourth. Those students account for 88 percent of students disciplined.

At Solon, only nine percent of students have an economic disadvantage. They make up 84 percent of all students disciplined.

The average Solon family brings in $15,000 more a year than the average Shaker family. Almost one-fifth of Shaker families are below the federal poverty line for a four-person household. Just four percent of Solon families are under such duress.

The socioeconomic breakdown of Shaker is unavoidable and will not change much in the coming years or decades. If economic disadvantage truly is tied to discipline, how much can Shaker’s discipline progress?

“It’s difficult,” Davies said, “but it can always be better. We just have to keep working and looking for options.” And Shaker’s discipline numbers are improving. The ratio of African-American to white students disciplined is below Shaker’s average over the past 10 years. In 2008, the ratio was 72 to 1.

“The frustration is, it’s never fast enough. Obviously, you want to eliminate expulsions and suspensions completely. You want to level the playing field,” Smith said. “But even then, I’m going to be looking for ways to make the numbers better.”

For Louisa, the only thing that could come sooner was the end of her 10-day suspension. She wasn’t reassured by a falling discipline rate. She wasn’t reassured by her teachers training to improve relations.

“The only way you can control your own destiny is with an education,” Smith said. Louisa wasn’t sure that the response to her mistake hadn’t taken her future out of her hands.

Investigations Reporter Elena Weingart contributed reporting.

Editor’s Note: The name Louisa is used as a pseudonym for a student interviewed who wished to remain anonymous.