Rebecca Harper guides a student’s hand for an art project.

Extending the Power of Preschool

What would it cost to bring first-class early education to all of Shaker’s children?

March 5, 2018

Some children are playing with blocks. Others read or listen to music. Projects and posters cover the walls. Bookshelves and tables divide the space. A constant hum of laughter and conversation fills the rest of the room.

Rebecca Harper sits at a table with three preschoolers. They are painting portraits of their families. Harper’s been teaching since 1999. Shaker’s First Class has been around for two of those years.

“I like this gray paint,” one of her students says.

“You like the gray? Well you are an artist,” she responds. “Here, do you want to open these as well?”

In the summer of 2014, the Early Childhood Education Task Force, created in pursuit of the district’s Five-Year Strategic Plan, met for the first time. Harper attended, along with 23 other administrators, teachers and researchers.

One of their tasks was to create an inventory of preschool programs available for students in Shaker. At Shaker last year, nearly 90 percent of students entering kindergarten had some early childhood education experience, according to the district. “But the quality of preschools,” said Dr. Teri Breeden, assistant superintendent of curriculum and instruction,“varies a great deal.”

“As you drive by preschools, you’ll see this thing called Step Up to Quality,” she continued. The Ohio Department of Education created the measure, assessing preschools on their teacher-student ratio and curriculum, among other things. It ranks schools using a five-star system.

“If you’re at the Beachwood shopping center and you go down the road, you’re going to see a preschool on the right hand side with four stars. You go down Lee and see one with one star,” Breeden said.

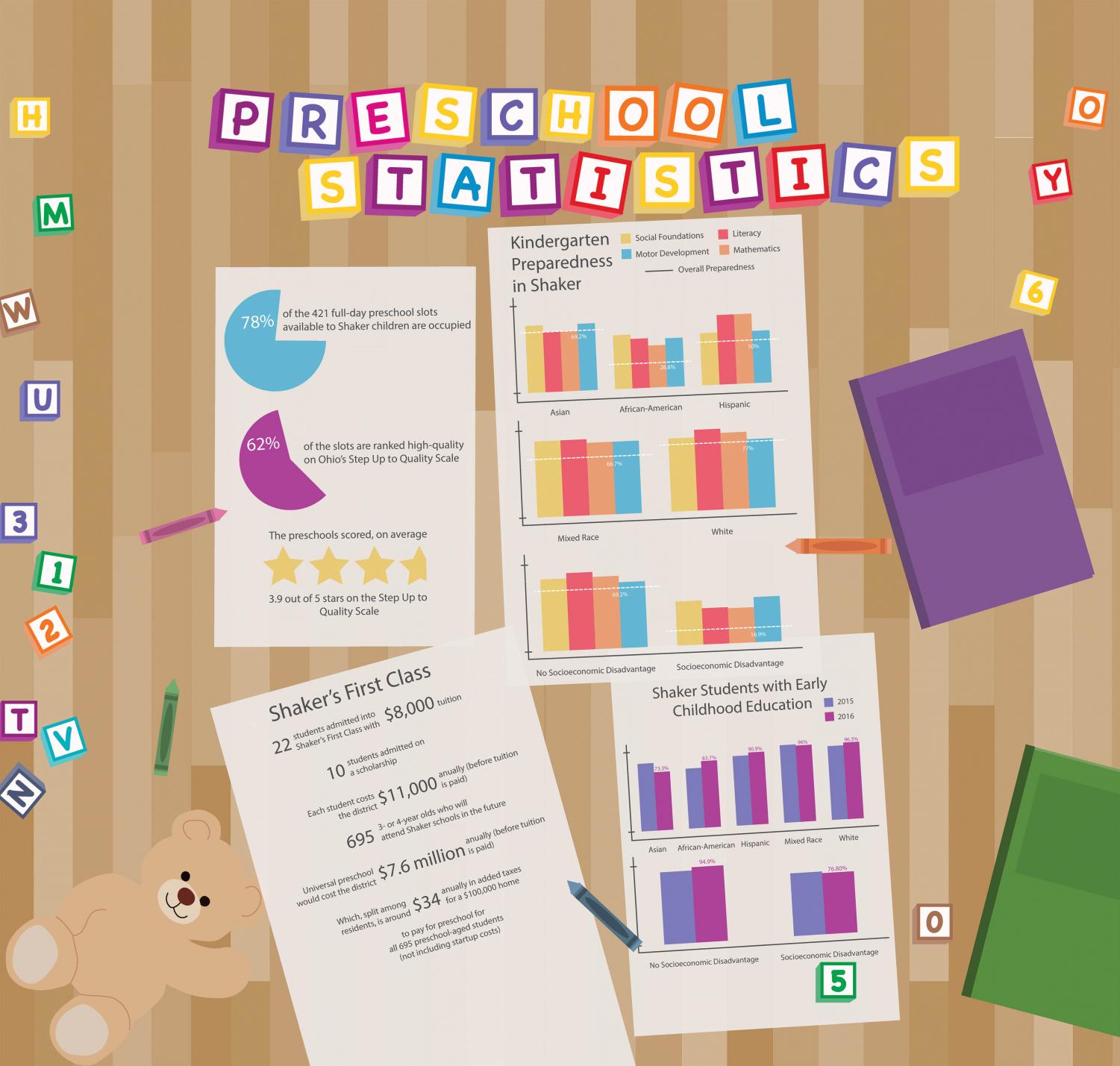

The task force found that there isn’t a lack of preschool seats available to Shaker residents. Students filled only 78 percent of the 421 full-day preschool seats around Shaker. But, there is a lack of quality. The DOE ranked only 62 percent of these full-day seats as high-quality. Part-day seats fared worse, with 27 percent ranked high-quality.

On average, preschools accessible to Shaker students scored 3.9 out of five stars on Ohio’s Step Up to Quality scale.

So, nearly 90 percent of last year’s kindergarteners went to preschool, but that isn’t the full story.

“There’s a test called the Kindergarten Readiness Assessment,” Breeden explained. “When the kids first come in, we test them with that. In Shaker, you’d think when the kids first come in, it’d be pretty high.”

You’d be wrong. Only 55 percent of the students entering Shaker kindergarten last year scored proficient on the assessment.

White students averaged 77 percent, African-American students averaged 29 percent and students who recieve free or reduced lunch — categorized as economically disadvantaged by the state — averaged 17 percent.

“One of the things that research will say is that the achievement gap is not something created by school,” Breeden said. “It meets you at the school door, when you first come into kindergarten.”

The KRA splits kindergarten readiness into several categories: social foundations, literacy, mathematics and motor development.

In all categories, Shaker’s white students scored higher than African-American students, and students with no economic disadvantage scored higher than those with economic disadvantage.

In the literacy and mathematics categories, scores of students without economic disadvantage were more than twice as high as those of disadvantaged students.

The district’s shaker.org equity resource page cites a single article on the achievement gap. It covers a speech by Stanford Professor of Poverty and Inequality in Education Sean Reardon.

“A point Dr. Reardon repeatedly made during his presentation is that . . . wide gaps in test scores exist by both race and income level at third grade, and they do not change much between third and eighth grades,” the article states. “Dr. Reardon said whole communities need to consider strategies that address the opportunity gaps that exist before third grade, including starting at birth, and that upper-income people and people in power may need to approach the issue with a different mind-set.”

A New York Times article from December 2017 titled, “How Effective is Your School District?” also used Reardon’s data. Currently, school districts are assessed on the achievement of their students. If 70 percent of Shaker students pass a state-mandated standardized test, and 50 percent of another school’s students pass the same test, Shaker would be ranked as a more effective school system. In the article, Reardon presented a new metric for effectiveness: growth of students — specifically from third to eighth grade. In Reardon’s analysis, districts such as Chicago Public Schools outscored many higher-income districts, with six years of growth for students over the five-year period.

Shaker ranks in the bottom sixth percentile in the same analysis. Reardon recorded 3.8 years of growth on average for Shaker students from third to eighth grade.

Dr. Kenneth Shores, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, worked with Reardon to collect the data. “The kids don’t really start taking tests until they get into third grade, so the average achievement level is only recorded from then on,” he said in a Shakerite interview. “One of the key findings is that the size of the gaps at grade three are pretty similar to the size of the gaps that we see at grade eight. So [schools’ gaps] aren’t really shrinking or growing a lot as the kids progress through school.”

Early learning, Shores continued, is where the greatest impact can be made.

Kristin Koenigsberger is another teacher for the Shaker preschool. “One of the biggest places you see the gaps here is the maturity of kids,” she said.

“Young kids are very egocentric; their world is all about them and what they know, so it’s hard for them to understand that there’s stuff that they don’t know,” Koenigsberger continued. “As you mature, you become less egocentric, hopefully, and you are more able to understand what you don’t know and why you need to learn.”

“We see a gap a lot in maturity level. Kids are still focused on themselves. They don’t want to sit because they don’t know why this lesson is important. And when they don’t sit, they start to fall behind already,” Koenigsberger said. “It’s not just sitting and listening; they want to play with the blocks in the way they want to play with the blocks. They don’t necessarily want to expand their repertoire and build a taller tower, a different tower.”

Harper said that when she gets to these students at age 3, this gap is not nearly as prominent. “It’s hard to see a gap because they’re all learning,” she said. “They’re all super young.”

“About this time in the second year, you can tell children who have not come from a high-quality preschool,” she continued. “You can tell from routine. You can tell from how they use materials and how they respond to materials.”

A student interrupts the interview. “Ms. Harper, Jackson’s foot was stuck in a blanket,” the young girl reports.

“Did you help him?” Harper asks.

“Yes,” the student responds and returns to her cot.

Harper continued, “Every kid should have a high-quality preschool experience.”

“That means exposure to pre-academic skills,” she said. “It means learning the routines and the expectations of a school environment.”

Harper cited at least four things that distinguished low-quality from high-quality early education.

First, good teachers. “All of the teachers here have two or three degrees,” Harper said.

Also important, Harper noted, is the student-teacher ratio. “We have enough staff in the room to hit every kid where their needs are,” she continued. “We have some kids who are reading — like, really reading — and we have some students who are still struggling to identify letters. That’s perfectly OK for them.”

Second, a strong curriculum. In Shaker’s First Class, “students journal, they write,” Harper explained. “Every Monday they have to write what they did over the weekend.”

She pulls out a student’s journal. Each page allows space for a drawing and text. “She’s writing phonetically here,” Harper explains. “We took a nap” is written in the notebook as “Wi tok a nap.”

Harper points out a newer entry. “I had two Thanksgivings, one in Hawking Hills, one at home,” it read.

But work isn’t the focus in preschool. Rather, it’s pre-academic skills they stress. “The way we communicate with each other, the way we solve problems,” Onaway Principal Eric Foreman said. “All those things that, for the majority of kindergartners, that’s the first month of school: How do I ask to go to the bathroom? How do I go to the office? These kids are getting a head start on all those soft skills.”

“Part of the soft skills include being able to sit down for story time,” Harper said. “If you have children who already know what classroom expectations are versus children who didn’t get that, then they can go into kindergarten already able to sit, focus, listen to instructions. They can process multiple levels of instruction.”

A low-quality preschool would have less structure and learning, Harper explained. It would be less of a classroom and more of a day care.

The third distinction between a high-quality and low-quality preschool education that Harper mentioned is the two-year setup. Students come in as 3-or 4-year-olds and are in the same classroom with the same teachers for two years. “You can look at research that says looping — which is a teacher term — works,” Harper said. “You don’t have to start at point A. You can just look at where they were last year and start from there. I’m able to do things that they might not start until midway through kindergarten.

“The fact that we get them for two years,” she continued, “and the families are with us for two years — there’s relationships. You lessen the gap of parents who feel like they aren’t part of the community.”

That’s the fourth indicator of a high-quality preschool: a community. “We had an event where everybody brought their own dish. There were siblings there, there were nannies there — everyone within their village,” Harper said.

“You’d have one kid running around, and some adult who wasn’t their parent would say, ‘Don’t run!’ Adults would prepare food for another person’s child,” she continued. “At that point it really became a village and not just a bunch of single individuals in a classroom.”

Charged with creating this high-quality alternative to the other preschools in Shaker, the Early Childhood Education Task Force suggested the idea of Shaker’s First Class.

In the fall of 2016, it came to life. Shaker repurposed two classrooms, one in Onaway and one in Mercer, for the use of the First Class. The preschool would accept students aged 3-5 for the two-year program. The requirements, according to shaker.org, were that the students be toilet-trained, families stay with the program both years and parents be available for family field trips. All 32 spots were filled. Tuition was set at $7,000 (raised to $8,000 the next year). Ten of the students accepted, a number corresponding with the percent of economically disadvantaged students in the district, were given full scholarships.

That November, the preschool received a five-star ranking by the Step Up to Quality measure.

Asked if she foresaw a visible difference when these students reach middle school, Harper responded, “That’s the expectation. Seriously. I think there’s going to be a noticable difference even next year.

“The expectation is that by third and fourth grade you’re not going to have to worry about the third-grade reading guarantee. By middle school,” she continued, “as long as they get all of the right pieces and parts along the way, they should be in honors-level courses.”

But there are 950 preschool-aged children in Shaker. Of them, 695 will enter the Shaker school system. Thirty-two is a start, but it’s just around 4 percent.

“I think universal preschool would be phenomenal,” Harper said. Universal preschool would be available to every student in a district. Available doesn’t just mean that there would be 695 spots; it means it’s affordable for everyone. It means every preschool-aged child in the district could attend.

“In my opinion, that’s the way we’re going to close the gap,” she continued. “We’re not going to close the gap through the likes of tutorial resources at the high school or middle school. We would be more effective, and the research says that we’re more effective, if we catch kids younger. If we had the opportunity to expand, if there was more access to Shaker families, you’re going to see a world of difference.”

Shaker’s First Class cost the district $351,000 last year. Per student, the annual cost of preschool in the district is $11,000. Therefore, imagining a universal preschool in Shaker providing access to all 695 students would require imagining a sum of more than $7.6 million.

If all students without a disadvantage paid their $8,000 tuition, the yearly cost to taxpayers would fall to $3.9 million.

The annual cost is not all to think about. The district spent another $44,000 on startup costs for things such as furniture, computers and classroom supplies. That adds up to another $1 million when accommodating 695 students.

Five million dollars is a big number. If that full cost were placed on the taxpayer, it would add approximately $22 to the local taxes for $100,000 homes. Every year after that, it would cost around $18 per $100,000 home valuation. If no student paid tuition so that the entire cost fell to the taxpayer, it would cost around $34 each year on a $100,000 home. The new facilities plan, which passed last May, is estimated to cost taxpayers nearly $132 annually on a $100,000 home, but it is of fixed duration.

“The biggest limitation is space,” Breeden said. “Right now, our enrollment is dropping. But to create classrooms for 300 more students — if there were 30 kids per class, that’s 10 more classrooms. But you have to have a lower student-teacher ratio. So space is limiting.”

Steve Wilkins, assistant superintendent of business and operations, agreed. “Most public school districts are organized for K-12 education — not PK-12. Factors such as enrollment, class hours and budgets can impact taking on this additional classroom structure,” he wrote in an email.

“Creating this additional classroom space could be done via construction, leasing space or increasing other class sizes to free up a classroom in the respective buildings,” he continued.

“I think this is what people in the community want,” Harper said.

Bridget McCarthy is one such community member. Her daughter, Alana, is in her second year at the preschool. “I would be all for it,” she said.

“I would be willing because I’m an educator and I know how important it is to have a strong preschool foundation. I would hope other community members would like to see that, to help the overall picture of the district,” she continued. “There are a bunch of families that will benefit who might otherwise have to look at centers that aren’t as structured or rigorous as our schools.”

“Every kid,” Harper repeated, “should have a high-quality preschool experience.”

Alana gets upset when she’s late for preschool. She says, “No! I won’t be there on time.” She enjoys her friends. She enjoys her teachers. Her mother sees her becoming her own person. She remembers Alana coming home and saying, “Mom, I was a risk-taker today because I tried the broccoli!”

“It’s going to make a big difference and impact on Shaker,” McCarthy said. “It might take some time because they’re only 3. But if we keep doing this it will make a big impact on the district.”

A version of this article appears in print on pages 26-33 of Volume 88, Issue II, published Feb. 8, 2018.