Is Hallway Diversity Enough for Shaker?

Student’s in Nathaniel Hsu’s 2015-2016, first and second period Advanced Placement Biology class demonstrate the divide between males and females in STEM classes.

A community may be known by the schools it keeps, but when the community is so diverse, the students end up keeping to themselves.

One of Shaker’s core values holds that diversity makes us stronger, but, especially in the high school, that same diversity is harder to point out than statistics may suggest.

“While I think there are many opportunities at Shaker, and the community is very diverse, I see a lot of segregation,” said sophomore Anna Sternberg. “We call ourselves a diverse place, but when I walk in the cafeteria, I see white tables and black tables — not a lot of mixing.”

On paper, Shaker is a diverse high school, with 52 percent of students African- American, 37 percent Caucasian, 5 percent multi-racial, 3 percent Asian and 2 percent Hispanic.

Once inside, however, students separate themselves.

“The school is extremely diverse” in economic status, ethnicity and interests in activities, but all of those types of people don’t necessarily interact or ‘play well’ with one another,” said sophomore Julian Hinze-Gaines.

High school cafeterias everywhere are scenes of social divisions, and one look at Shaker’s lunchroom reveals that students segregate themselves here as well, despite the community’s reputation for and commitment to embracing diversity. These divisions are visible in classrooms, sports teams and student activities as well.

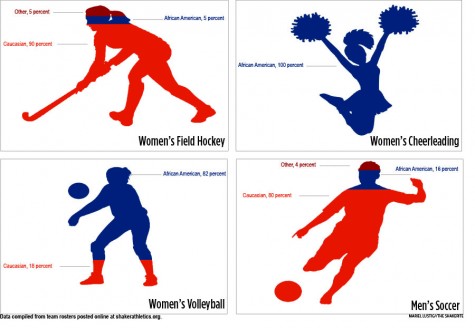

Most fall sports teams do not resemble the diversity of the school. Women’s tennis is one of the few teams that displays racial variety. This year, among the athletes comprising the varsity A, varsity B and junior varsity women’s tennis teams, 56 percent are Caucasian and 26 percent African-American. Eighteen percent of the tennis athletes identify as “Other,” a designation that means they do not identify as Caucasian or African-American. Women’s tennis athletes are significantly more diverse than those comprising other fall teams.

“The team’s diversity has definitely benefitted the team,” said captain Allison Kao. “We’ve gotten to know each other so well to the point that our differences and varying perspectives have impacted one another.”

Tennis has long been affiliated with white, affluent — even country club — culture, but this identity is changing nationally as more African-American athletes, such as Venus and Serena Williams, establish themselves as dominant professional tennis players. It seems that Shaker’s women’s tennis program mirrors this trend.

Players and coaches from less diverse teams, however, offered some theories about their sports’ homogeneity. They frequently cited economic barriers to participation.

Sophomore figure skater Maddy Suna said the figure-skating community lacks diversity.

“Mostly everyone I skate with is white and from an upper middle-class family,” said Suna. “I think this [imbalance] exists because it is one of the most expensive sports. If you want a good pair of skates, it’s probably about $300, plus the blades are another $200. Then, you also have to pay for ice time, dresses, shows, competitions and a skating bag.”

Suna noted that early skating programs are more racially balanced, however.

“If you look at Learn to Skate, it is pretty diverse because people can afford to pay the $5 to rent skates and the money to enroll into the program,” she said. “But, once you get to club, it is often too expensive for many families.”

Head field hockey coach Hilary Anderson said that the costs associated with playing sports can limit participation.

“I believe the main reason for the lack of diversity [in field hockey] is the overhead cost — the stick and mouthguard, for example,” she said.

Intermediate to expert field hockey sticks at Dick’s Sporting Goods cost $60 to $250.

Although racial and ethnic diversity at Shaker is easy to see, economic disparity among the student body is less obvious — but increasingly present. According to the 2005 Shaker Heights City Schools Fact Book, the poverty rate among all students was 23.3 percent. By 2010, the district reported, it had risen to 31.6 percent.

The district Fact Book does not present poverty rates by racial or ethnic population. However, in the United States, poverty rates among ethnic groups vary widely, with African-American and Hispanic Americans experiencing poverty at more than twice the rate of whites.

According to US News and World Reports, the national poverty rate for non-Hispanic whites was 10.1 percent in 2014. They accounted for 61.8 percent of the total population and 42.1 percent of the people in poverty.

By comparison, the poverty rate for African-Americans was 26.2 percent. For Asians, the 2014 poverty rate was 12.0 percent and among Hispanics, the 2014 poverty rate was 23.6 percent.

Some activities, such as band, more accurately represent the racial composition of the student body, perhaps because of efforts to remove financial barriers like those that are present in sports.

“I think [band is diverse] because we had to play an instrument in fifth and sixth grade,” Suna said. “The kids who genuinely enjoyed it continued, and those who couldn’t afford instruments can get them through the school for free.”

Band students are also given the opportunity to raise funds for international trips, which typically cost about $3,000. The band travels internationally every three years, and students often start their fundraising efforts as early as fifth grade. The band booster parents also offer partial scholarships.

“We are always told the excitement of going on a trip to a foreign country, and those who can’t afford it can get financial help,” Suna said. “Shaker makes it very accomodating for anyone to play an instrument.”

Band Director Tim Clemens acknowledges that band can be an expensive activity.

“Uniform fees are paid through the boosters,” he said. “Some generous parents pay two or three times the cost of one uniform to pay for others’ uniforms.”

Additionally, initiatives such as Shaker’s Beyond the Desk program strive to remove socioeconomic challenges from the equation. By providing a stipend to students who would otherwise not be able to afford extracurricular costs, the scholarship program enables those working students to work fewer hours and attend activities instead.

“Schools can’t and shouldn’t lift students’ socioeconomic standing,” said Beyond the Desk founder Marcia Brown (‘15) stated in a Shakerite article titled Proposed Stipend Program Could Help Students Do More. “However, schools can help ameliorate equality of opportunity within their red brick walls.”

Beyond sports and activities, the racial and ethnic division within the high school is evident in classes, which, while not entirely divided, do not match the high school’s diversity.

“[The classes] don’t reflect the total diversity of the student population of the school, but it is not solely one ethnic background,” physics teacher James Schmidt said. “I look around my AP classes and generally see white, middle-class kids,” Suna said.

In the case of the IB diploma program, now in its fifth year at the high school, English teacher Charles Kelly said diversity is a goal served by promotion.

“I think that we’re are trying very hard to get access to all levels of students in all groups whether it’s in racial diversity or other kinds of diversity,” he said. “Because it’s a new program, I think we’ve done a degree of work towards trying to make students aware of the program.”

In addition to student separation, there is also a lack of diversity among the high school faculty.

Currently there are no African-American teachers teaching Advancement Placement or International Baccalaureate classes at the high school, which means minority students in the AP and IB tracks do not see themselves reflected in classmates or teachers.

“I think [the AP/IB staff] pretty representative of the general teaching staff as a whole,” said math teacher Caroline Markel. “And think that there could be more diversity in the teaching staff as a whole.”

Evidence of racial and ethnic separation within the student body is abundant whether this self-imposed segregation is an issue of nature or nurture.

“I think that people gravitate towards things that are comfortable for them,” Superintendent Gregory C. Hutchings Jr. said. “The issue not only here in Shaker Heights but globally [is that] people typically don’t like to be taken out of their comfort zone, so you may gravitate towards someone who looks like you or someone who acts like you or someone who has the same values as you or part of the same circle that you’re in.”

Because of this natural tendency, Hutchings said, clubs, organizations and sports are often populated by people who share characteristics and experiences.

This belief that segregation, even in diverse communities, is due to learned experiences, is common among Shaker students.

“I think we stereotype by experience. [For] example, no one is born with prejudice,” Sternberg said. “Most typically grow up in a household with people [who] look alike and have similar values, so we make friends with people who seem similar to us because this is what we are familiar with.

“When given the opportunity to learn about other cultures or races, people usually take it, but in general most people seem to stay close to what they’re used to.”

“I do believe there is some degree of people unintentionally, or intentionally, grouping with people of similar ethnicities and cultures,” said Hinze-Gaines. “I consider [the grouping of non-similar persons] to be fairly unnatural, but [it has been] taught in little ways to every person as they develop into young adults, and that’s what creates the divide in the teen years.”

“I think people segregate based on how they perceived their similarities and differences,” said nurse Paula Damm. “So I think if you have a group of kids and adults, the kids will all hang together and the adults will all hang together.”

The difference between the school’s reputation for diversity and the reality of student interactions is a concern for Hutchings.

“I think that we need to find a way to not only say we embrace diversity, but really get engaged in diversity,” Hutchings said. “What I mean by that is a lot of our students say that they attend Shaker High School, which is very diverse high school, but a lot of the diversity happens in the hallways.”

Hutchings wants to improve integration within the high school.

“When you’re in the cafeteria or you’re in a specific classroom, you don’t see that same diversity that you see when you’re walking down the halls,” he said. “What I would like for us to have is that same kind of diversity in our hallways throughout everything that we do, whether it’s a program or an event or a sport or the cafeteria or our classes.”

Hutchings’ goal supports a common belief that growing up in a diverse community and attending a diverse school gives students an advantage far beyond high school.

Shaker students think that’s true.

“I think being with lots of different people during high school will prepare me for all different sorts of people I may have to work with the in future, like [in] college,” said junior Gloria Ng. “Being with lots of different people is good because there are lots of people in this world, and being accepting of lots of different types of people is good.”

A U.S. News and World Report examination of this belief determined that diversity in the educational setting is important for eight reasons.

The report concluded that diversity expands worldliness, enhances social development, prepares students for future careers and a global society, increases a student’s knowledge base, promotes creative thinking, enhances self-awareness and magnifies the power of a general education by providing multiple perspectives.

Parents agreed that diversity is an asset when entering the “real world.”

“Diversity was definitely a factor when we decided to have our kids go to Shaker,” said Mike Yost, father of freshman Lyle Yost. “I, personally, was raised in a small town in Pennsylvania with essentially no diversity. My wife and I both have always felt that our kids should live in as diverse a setting as possible to shape their perspectives early on in life,” he said.

“We definitely feel Shaker’s diversity will help our kids throughout their lives because they see people as people, not as ‘different’ because of ethnicity or race or other factors.”

In keeping with this belief, colleges typically have formal diversity programs and personnel.

“We try to create diversity in college by being respectful in people’s views and perspectives in the way that they see the world,” Andrew L. Bundy, library assistant and chairperson for Kent State’s Student Diversity Committee said.

“We also foster relationships by offering campus events that foster diversity in many different aspects, from conversation to being able to share experiences that will expand their horizons,” he said.

“Overall, we try to make our campus a strong, diverse environment and we try to experience this in ourselves as well.” Bundy said that coming from a diverse high school is an asset in college.

He attended Liberty High School in Youngstown.

“Coming from a diverse high school, I have to say that it does provide some advantages in college and in life as well,” Bundy said. “I had many friends who came from different backgrounds in which I was able to understand how interesting our world is as a whole.

“If it wasn’t for my experience with diversity in high school, I would not be who I am.”

Shaker alumnus Jeron Gaskins (’15), a freshman at Capitol University, agreed with Bundy’s assesment.

“I personally think the diversity in Shaker prepared me for college,” said Gaskins. “Because unlike what we are constantly told [in school], it is even more diverse outside of Shaker because outside of Shaker is the whole world.”

Gaskins has taken his experiences with diversity at Shaker to his school’s diversity office.

“It’s really interesting getting to work with all these different groups on campus that want to be represented,” he said.

While coming from Shaker might give you an advantage in some aspects of college, it can also have a negative effect.

“The diversity at Shaker has given me really unrealistic expectations of other people when it comes to their cultural literacy,” said Shaker alumna Whitney Erin (’15).

Erin is a freshman studying at Ursuline College.

“I’ve never been around so many white people who were comfortable jokingly using the n-word in my presence or touching my afro without asking. “Additionally, people are really ignorant about classism, racism and homophobia compared to Shaker students,” she said.

“At orientation we did SGORR-esque activities and I was usually the only one to raise my hand when they asked who’d done them before.“Thankfully my college has a phenomenal department of multicultural affairs.”

Given the general acceptance that diversity is desirable and beneficial, should Shaker worry that the cafeteria is segregated, the sports teams are homogenous, the faculty is overwhelmingly white? Or is simply attending school and living in a diverse community enough, even though students do not experience diversity in every school setting or activity?

Yost said, “[Students’] baseline for tolerance of people’s differences will be much higher growing up in a diverse community like Shaker, and they will have the chance to live without barriers that others, from less diverse backgrounds, have to learn to tear down in their lives. Shaker’s diversity is certainly a blessing for us all.”

Investigations Reporter Elena Weingart and Journalism I Reporters Andrew Mohar, Claire Ockner, Kaiah Callahan, Katrina Cassell, Nicholas Lorenzo and Shaye Robbie contributed reporting.