Didn’t Do It? Don’t Worry, You Have Another Chance … and Another

Under new policy, SMS Teachers cannot assign zeroes, must accept late work as district standardizes grading

January 10, 2015

Middle School Principal David Glasner speaks to parents in the middle school library after he was hired last spring. One of Glasner’s first initiatives as principal has been instituting a new, standardized grading policy.

No more zeroes for missing work. Mandatory acceptance of late work. Chances to retake tests, rewrite plagiarized papers and redo assignments.

When the year began at Shaker Middle School, a new era of grading began as well. And similar changes are coming to the high school as the district, in keeping with its strategic plan, pursues “consistent grading and homework practices/protocols,” designed to provide unlimited opportunities for mastery, beginning with elementary schools, followed by the middle school and after that the high school by 2018.

David Glasner, in his first year as middle school principal, came to Shaker knowing that revising the grading policy would be an immediate project, and over the summer, teacher leaders and administrators met to discuss the middle school handbook — in which the new grading policy would be printed. The middle school’s resulting new policy is a “living” document, according to Glasner, that staff will continually revise.

The district’s embrace of mastery-based learning, a philosophy that requires students to demonstrate that they have learned, or mastered, content before moving on to advanced concepts or skills, and the resulting changes in grading policies reflect education reforms that are spreading across the nation.

Middle School Policy

Glasner began reviewing the grading policies of department chairpersons and other teachers this past summer. He and his assistant principals, Miata Hunter and Robert Rea, analyzed “specific language, looking at the math,” he said.

Glasner formed an internal “leadership institute,” comprising department chairpersons, team leaders and other teachers.

Glasner noted the new grading policy, which the leadership institute devised, is “similar” to that of his previous school, the Urban Assembly Academy of Government and Law in New York City. This public high school, a part of the Urban Assembly schools network, had 312 students, 42 percent of whom were African American, 52 percent of whom were Hispanic, four percent Caucasian and four percent Asian, according to New York City’s Department of Education’s 2012-2013 Quality Review Report.

“We presented [the policy] to them, they got input and we got that solidified by the beginning of the school year,” Glasner said. The policy is published in the Middle School Student Handbook, which Assistant Superintendent Marla Robinson and Superintendent Gregory C. Hutchings, Jr. review.

Glasner wrote in an email that some grading policy changes resulted from “input from the leadership institute participants.” They included alignment to IB MYP standards, inclusion of the IB rubric in the policy and fixes to the errors in the grading curve. The policy also included “additional information and clarity on effort and citizenship grades based on some of the conversations we had at the leadership institute.”

However, some of the teachers felt their concerns were not addressed. “I advocated (along with a few others) pretty passionately for teacher-driven deadlines in terms of the late policy, for example, to no avail,” English teacher Erika Pfeiffer wrote in an email. Pfeiffer is a team leader and teacher leader who attended the leadership institute.

The new policy allows students to turn in late work with “up to 30 percent deduction of the final grade,” but does not specify how late the work can be submitted. She acknowledged that when the policies “were initially being written at some point prior to our meeting, that there were other teacher leaders whose input went into their creation.” Glasner clarified, however, that the draft presented to the institute was written with his assistant principals.

So far, eighth grader Harlan Friedman-Romell has noticed a change.

“The classes are easier this year than last, but teachers still take off points for late work,” said Friedman-Romell. “You were always able to turn in late work, just the grade would suffer. Some of my teachers last year did not allot the appropriate time for late work from absences, and I know a lot of other kids also had similar problems.”

Friedman-Romell said he thinks it’s OK for students to turn in late work, and that most students at the middle school turn work in on time. However, he admitted that last year he had few missing assignments, saying “this year I have quite a few.”

“[N]ot everyone was ‘on board’ with the policy (no zeroes, curving all grades below a certain score, etc.) but we are responsible for enforcing it,” Pfeiffer said.

Dexter Lindsey, middle school MYP coordinator, emphasized the institute’s importance. “Prior to the leadership institute, the grading policy was consistent within the subject areas,” he said. “The leadership institute allowed us to go toward a building wide standardization model of grading practices, which is what teachers wanted.”

Seventh grade Individual Societies Department Chair Mike Sears also participated in the leadership institute. (Individual Societies was previously known as social studies and changed to align with IB requirements).

“There were a few things that we discussed at the leadership institute, and there were several brainstorming sessions and a couple minor changes made to the handbook,” he said. “However, I do not recall much discussion about the grading policy. The impression was that this part of the handbook was not up for discussion.”

Hutchings said that he is typically involved during a process such as the grading policy’s development, though he may not attend every meeting. He demands that a teacher always be involved in the document’s creation.

“If [a] teacher was involved and administrators, [and] at times parents as well as students, then, it’s easier for me to support than something that just comes from a principal,” Hutchings said.

Glasner emphasized that this policy is not static.

High School Principal Michael Griffith speaks about potential changes to the high school grading policy. Like the high school, the middle school now no longer allows zeros. The minimums grade is now a 45 percent. “Beating you with a stick and saying, ‘I’m just going to give you zeros,’ — that’s not motivating you, particularly the student who is already disengaged,” Griffith said.

“I told the teachers, this is meant to be a living document in that we are constantly trying to improve our grading policies,” Glasner said.

Sears said that part of the reasoning for the policy was to make the middle school more like the high school. While the high school does not yet have a standardized grading policy, it does not allow teachers to give zeros for missing work until the end of a grading period and encourages redos, retakes and revisions.

Hutchings and Robinson made no changes to the new middle school policy when they reviewed it.

“Prior to the request being made, I think that we set up some parameters. We didn’t discuss exactly what the cut off would be about, just the fact that if you give a student a zero, in a sense it almost prevents them from passing a course, depending on the weight that actual assignment is given,” Hutchings said.

One of the biggest changes in the new policy is the purge of any zeros from grades. The base grade – the lowest grade a student can receive – is a 45 percent.

“This is the thing that most people get kind of up in arms about, because what it feels like is that students are getting something for nothing,” said Camille A. Farrington, an associate professor at the University of Chicago’s School of Social Service Administration.

Farrington was referenced in the policy as a source of scholarship. “Students who aren’t doing any work are getting 45 points. Particularly to kids who did the work, it feels unfair.” However, Farrington believes the change doesn’t alter the letter grades students receive, but gives students more opportunity to pass.

“Getting a 45 or a 50 doesn’t sound nearly as bad as getting a 20 or a 10 or a zero,” said Glasner. “But if you think about it, in letter grades, which is ultimately what it comes out to be, if you get a 50 or a 45 you’re still failing.”

According to Sears, some teachers so far have said their grades are inflated while others report little effect.

Farrington explained the reasoning behind the shift. “I would argue that the problem is a mathematical problem and not a problem of fairness,” she said. She thinks that the problem lies with the conversion from a 100-point scale of grading to a four-point scale for GPA calculations. She cites the unequal intervals for letter grades as the problem.

“It’s not an equal interval scale,” said Farrington. “Zero-59 is an F, and then you et 10 points for all the other grades. Making the lowest grade a 45 is actually just truncating the lower part of the scale.” It’s no longer that 0-59 is an F, with intervals of 10 for every other letter grade. Now, F is only an interval of 15, making the intervals more similar.

“Really a zero should be more in line with a 50, but we wanted to distinguish between something that was not turned in at all and something that got a low grade,” Glasner said, explaining why the 45 base grade is below a 50.

Farrington believes using the four-point GPA scale would be more efficient for grading, as it would eliminate the conversion. However, in its present imperfect form, the alternate–the 45 percent base grade — is criticized.

“I think some parents look at it as ‘My kid should get a zero,’” Sears said.

Middle school parent Kim McFadden disagreed. “There have been many challenges with missing assignments,” she wrote in an email, “but I have felt the teachers have been receptive to working with the boys in reference to accepting the late work rather than getting a zero.”

“When the kids know they can make a difference with a little effort, they not only produce the work, but they try harder to produce QUALITY work because they want to earn as many points as possible,” wrote Pfeiffer. “When you can get them to engage at that level, they learn.”

Pfeiffer said students no longer have eight percents and thus aren’t discouraged from completing future assignments that, under the traditional grading system, would have increased their averages but still left them failing.

“People feel like they’re getting something for nothing, but in reality it’s still an F,” Farrington said.

“Very few people present it or explain it that way,” Farrington said. She notes that on a 100-point scale, a zero is an outlier that drags the average down. “Anybody who knows anything about math can see that that’s true.”

However, students at the school find the policy benefits them in more ways than expected. “I do like the policy very much, but probably for the wrong reasons. It allows me to have missing assignments and still have A’s,” Friedman-Romell said.

Griffith said that it should be a 50-point scale or a scale of 100 with 20-point intervals. A 100-point scale with unequal intervals is “mathematically wrong,” he said. “We’ve been doing this wrong for I don’t know how many centuries.”

“The truth is that if you don’t do something, or you do something poorly, you’re still failing. This hasn’t changed it,” said Glasner. “We’ve changed it so that mathematically, if you continue to fail, or you are failing, mathematically, you have some hope of moving into a passing range.”

Pfeiffer however, believes that while this does give students hope, too much leeway in deadlines creates a culture of infinite second chances.

“I feel it’s unfair to the students who do what they are supposed to do and adhere to deadlines,” said Pfeiffer. “Most importantly, it sets students up for later failure if we pretend that there are never real deadlines and that there are always second chances.”

“I think the stakes for students, if you inculcate the notion over time that you can redo everything, over time they’ll be up for a life-devastating problem,” said Ken Ledford, associate professor of history and law at Case Western Reserve University.

Before the policy was implemented, the administration discussed these questions of redos and base grades.

“So the conversation that we had prior to the grading policy being created or established was the fact that we want to make sure that students, one, they are held accountable,” Hutchings said. If students are able to make up a grade or receive a 45 at worst, “some people say that that causes a student to be lazy,” he said. “And I don’t agree with that.”

“I think that it tells the student that you’re going to be held accountable for doing the work,” said Hutchings. “It doesn’t mean that you can’t get an F, it just means that you can’t get a zero.”

“Beating you with a stick and saying, ‘I’m just going to give you zeros,’ ” said high school Principal Michael Griffith, “that’s not motivating you, particularly the student who is already disengaged. They’re not jumping up and down saying, ‘That zero matters to me.’ ”

Farrington added that teaching students and compelling students to do work shouldn’t just come from grade incentivization.

“I think it’s important to kind of talk to kids both about the importance of what they’re learning and the importance of learning how to be a good student,” she said. When teachers assign students tasks, teachers usually let the students decide how to accomplish them, according to Farrington, who also taught high school for 15 years. Instead, Farrington said teachers should make it “part of the culture” and “a social part of what happens in class” as they learn how to manage assignments and develop as “strategic learners.” She believes that this grading policy is “a good opportunity to focus on that.”

Hutchings doesn’t want students to be able to receive an F on an assignment and move on without mastering the material. He wants to ensure that students complete the work at a higher level.

“We want [students] to be resilient and persistent and to have the grit to get the job done,” said Hutchings. “It may not be perfect, but you will finish it. And I think that that sends a louder message that ‘OK, if you don’t do it, you get an F, and we’ll just move on.’ ”

“I think the goal for us is to work with the student, work with the parent so that the work is actually completed—that not completing your assignment is not an option,” Hutchings said.

Onaway Principal Amy Davis explains how Onaway’s grading policy works, and how it meshes with Common Core State Standards and the Middle Years Programme. The report card at Onaway spells out each of the many skills students should master at the end of grading periods according to the outlined curriculum and the Common Core Standards. This style of assessment might be an option for the middle school in the future.

“I think that is a standard that we need to have across the board in Shaker Heights,” said Hutchings. “I think that’s going to make us even greater as a district. You know, we’re already great, but what’s going to make us even greater is making sure that 100 percent of our students are held accountable for completing their work.”

Hutchings believes that giving zeros is destructive to this completion philosophy.

“I mean, the research shows that providing students with zeros is really detrimental to their educational careers, and it doesn’t help a student in regards to being a better student or having a better educational experience in our schools,” Hutchings said.

Glasner reinforced this idea by adding that students do the assessments to show mastery and learning.

“I also want to emphasize that we don’t give assessments just to measure completion,” said Glasner. “So the emphasis is on students doing the assessment because it is a learning experience for everyone involved.”

“I have found the teachers motivated to reteach or go over the material with my boys so they understand the material rather than the boys scoring poorly and never truly ‘getting’ it,” wrote McFadden. “In many of the subjects, a student needs to comprehend the material to be successful in moving forward.”

In particular, McFadden wrote, “Having the ability to stay after school and meet with the teachers during conference time is a wonderful resource.”

Sears said that many parents are confused by the reasoning behind the new policy. “You have to explain to parents the policy, and when I’ve explained it a few times I’ve just gotten a confused reaction,” said Sears. “[It’s] more an educational thing. Using teacher language, parents just don’t understand why you would get credit for something you didn’t work on at all.”

However, McFadden said her sons’ teachers have communicated with her well so far. “I felt all of my sons’ teachers did a good job in explaining the new grading process during curriculum night. In addition, all of the teachers provided syllabus with their grading information,” wrote McFadden. “My experiences with my boys’ teachers have been positive. I have found the teachers to be responsive to emails and communication. I truly get the sense the teachers want to my boys to be successful learners.”

Giving zeros lowers students’ self-esteem and dampens any hope a student might have of passing, Hutchings said. “You still want to give somebody an opportunity to redeem themselves so if they have a change of heart and they want to be devoted and educated, we want them to think they can actually make a difference and change their grade.”

Furthermore, Hutchings and Griffith believe that allowing a student to get a zero means the student didn’t develop mastery.

“The notion, I think, that I’m just going to give you a big fat zero and let you off on the way to the next assignment, I didn’t hold you accountable to mastery,” said Griffith. “I may have held you accountable in terms of behavior, but academically I didn’t hold you accountable to mastery. So if I’m intending to say that my class is about every student demonstrating mastery, I can’t just put the big fat zero on the grade book and walk away.”

In addition, this policy gives students a better chance of passing the course.

“So, if a student fails a test or paper early on in the semester, and then shows growth over time, this will allow them mathematically to pass, whereas in the past, mathematically, that may not have been the case,” Glasner said.

“The benefit I have seen for students is that it takes a lot more than it did before to render a grade completely unrecoverable,” wrote Pfeiffer. “This does actually seem to encourage them to put in an effort to bring their grades up because they know it’s possible to do so.”

Griffith added that this idea has been a part of his work on grading policy. “That’s [been] my work with the staff, is the automatic zero doesn’t matter for those kids,” he said. “If it mattered for those kids, you would see a change in behavior. If it’s not motivating them, then it really isn’t a good tool.”

Students notice the no-zero policy in their grades, although not all teachers abide by it. “Some of my teachers forget the ‘no zero policy’ and I have zeros for homework assignments, where in reality, no one in the entire school should have an assignment lower than 45 percent,” Friedman-Romell wrote. He added that no-zeros make it easier to maintain higher grades, if students test well.

In the policy’s first one and a half quarters of use, Sears hasn’t seen a big change.

“To be honest, I would say that I’m seeing the same behaviors from seventh graders I’ve seen for 20 years,” said Sears. “I think sometimes we think that grades and points are motivators, but there’s some kids who are really doing well regardless of what the policy is. They have the skill and work ethic and they’re doing really well, and then there’s other students who maybe they’re not reading at grade level or they have other problems outside of school. So the 45 percent doesn’t matter to them in terms of their effort.”

A committee of high school faculty and administrators will develop a standard grading policy. As for the 45 percent base grade, Griffith is unsure whether such a policy could work at the high school. “Forty-five percent minimum is an attempt to answer those questions. Whether that’s the best answer is open for debate,” Griffith said.

The new policy also has provisions for students who fall behind first semester. It outlines a path to pass if the student struggles or endures extraneous circumstances such as an extended absence due to illness. If students fail the first semester, the grading policy lets them pass the year if they receive a minimum of a C second semester. The students must also pass a cumulative exam at the end of the year, such as a final or a standardized test. Then, the student’s teacher must endorse passing the course.

Glasner said this situation rarely occurs. “In middle school, it doesn’t really apply as frequently. And even in high school, I can probably count on one hand the times that this actually came into play,” he said. “But the reason that’s in there is because it promotes the idea of mastery-based learning, that it’s about mastering learning objectives.”

When it does occur, however, this policy gives students a another chance. If the student succeeds in the second semester on the cumulative exam, “those are two strong pieces of evidence that you’ve mastered the learning objectives for the course,” Glasner said.

However, Glasner said that research shows it’s very difficult to catch up once you’ve fallen behind. He added that people who fall into this category do not intentionally fail first semester. To pass second semester, they might get a tutor and “try to figure out how to pass second semester,” he said.

“Here at the middle school, we have conference time, so, you know, in that situation, we do recommend that students attend conferences and that they go to tutoring center,” said Glasner. “We do have internal supports for students who need extra support and extra time. Sometimes parents will hire a private tutor, but that’s up to the parents.”

When asked if the policy is a substitute for social promotion, a policy intended to promote students to the next grade level even if they’ve failed one or more classes to keep students with peers of their age group, Hutchings and Glasner both responded, “No.” Hutchings expanded on his answer saying he thinks the policy “gives students just more hope and more options and more opportunity to be successful, to move forward,” he said.

Onaway’s curriculum follows this document. This is the fourth grade page, which outlines the skills students should master in MYP’S program of inquiry. Each theme listed horizontally is pursued in each level, with an added level of complexity each year. Below are the units that Onaway uses for their students to meet the requirements.

At this time, Glasner isn’t sure how this will change the graduation rate, but “mathematically this gives students a chance to dig out of a hole,” he said. “The grading policy wasn’t designed with the goal of trying to reduce our retention numbers, but with the goal in mind of demonstrating meeting learning objectives.”

However, Pfeiffer hasn’t seen a big increase in students doing revisions and retakes. “I have been a little disappointed in the lack of response to the opportunity to retake quizzes and tests, and to revise writing assignments for additional credit,” she wrote. “I’m not going to force the issue, but it surprises me that students don’t take advantage of such easy improvement.”

“Some students struggle with the weights of assessments, but overall the students appreciate the opportunity to retake assessments to improve their grades,” SHMS IB Coordinator Dexter Lindsey wrote of the effect of formative and summative weights, and redo opportunities.

The formative portion of a student’s grade allows students multiple opportunities to complete an assignment for mastery, including redos, retakes and revisions. This component of the grade is usually weighted less than the summative component. Typically, formative includes homework, projects and work done outside of class. Formative includes unit tests and other assessments. Depending on the teacher, quizzes can be categorized under either.

Friedman-Romell explains how this division of the grade effects some students.

“The largest portion of our grade relies on testing, so some kids (including me) don’t have stellar grades in the formative category, but we have good test grades,” wrote Friedman-Romell.

“If you are a good test taker, then you don’t have to try in the formative category due to the no-zero policy,” he wrote.

Much of the new policy correlates with the expectations of Shaker becoming an Middle Years Programme district. If approved, Shaker will be one of seven pre-k through 12 MYP districts in the United States. To convert to letter grades, teachers must adjust from a 100-point scale of grading to a 4-point scale of letter grades. MYP’s scale further requires teachers to convert grades from a 0-8 scale, to a 100-point percentage grade to letter grades.

This creates inaccuracies of conversion, as the conversion from the MYP scale to a 100-point scale is not a perfect crossover, in addition to adding to teachers’ burdens.

“Now the middle school currently, in their handbook, has a conversion from these MYP grades to a traditional grade. Now at the high school, we don’t have a standardized form of that, and MYP says that we shouldn’t,” said John Moore, high school IB MYP coordinator and science teacher.

“That conversion would be up to the professional discretion, and that is the wording that they use . . . the interpretation of these scores and what that means for traditional grades to the collaborative, professional discretion of the teachers teaching that subject at that specific course,” Moore said.

While the school is required to fulfill the state requirements, the Ohio Department of Education still wants districts to maintain autonomy.

The ODE does want districts to adopt policies that align with the Common Core Standards, according to John Charlton, associate director of communications for the ODE.

“We believe that while a district may have an overarching policy on grading, each teacher should be given some flexibility to make their own grading decision that again meet the needs and priorities of the students in that class,” Charlton wrote in an email interview.

“Every student learns differently. At ODE, we want to see results,” wrote Charlton. “The method in which a student achieves these standards is up to the districts, schools and teachers.”

Differentiated Learning and Mastery-Based Grading

The shift from letter grades to standards-based measurements begins with grading systems. It culminates in an entirely different way of gauging students’ learning.

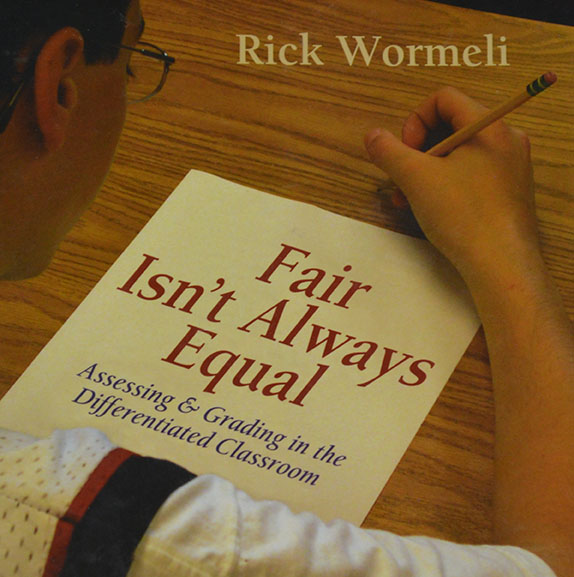

In “Fair Isn’t Always Equal: Assessing and Grading in the Differentiated Classroom,” Rick Wormeli and Robert J. Marzano outline this new philosophy in 16 chapters. Griffith bases some of his ideas for a potential high school grading policy on Wormeli and Marzano’s research.

The middle school grading policy identifies Wormeli, Marzano, Farrington and Margaret H. Small as sources for its inspiration. Glasner also used his background at the Urban Assembly as a foundation for building the policy.

Author Rick Wormeli, in his book “Fair Isn’t Always Equal,” discusses the merits of switching to mastery-based grading and how teachers should assess students using tools such as allowing redos and extending time for makeups. He also emphasizes the need for differentiated teaching, a style that calls on teachers to address each student’s learning differently based on their learning strengths and weaknesses.

To measure mastery is to measure learning, according to the philosophies of Wormeli and his cohort. They define the model as “a collection of best practices strategically employed to maximize students’ learning at every turn, including giving them the tools to handle anything that is undifferentiated.” Differentiation is an educational term that means adjusting teaching styles and assignments specifically for individual students. Thus echoing his book’s title, they write, “What is fair isn’t always equal, and our goal as teachers is to be fair and developmentally appropriate, not one-size-fits-all equal.” The two authors believe in employing the differentiated learning model, which does “what’s fair for students.”

Marzano is CEO of Marzano Research, the executive director of Regional Educational Laboratory created by the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences and a recipient of the 2008 Brock International Prize in Education. Wormeli is one of the first Nationally Board Certified teachers in America, has written four books on standards-based education and is one of Disney’s American Teacher Awards 1996 Outstanding English Teacher of the Nation.

Although other researchers may not call it “differentiated,’ they agree with Wormeli and Marzano’s premise. Farrington said that diverse schools face the challenge of meeting the problems of students from varied backgrounds, and often, it’s possible to address part of it through a grading policy. “Schools can’t change the fact that certain kids have to work every day after school and take care of their siblings,” she said. “School themselves are limited in what they can do, but they can minimize that harm that causes in their academic performance, through late work policies. Our one good way of doing that, the way that impacts students who don’t have time to study for the test, [is] setting aside time in the school day that gives them extra time to do their make-up work during the regular school day.”

Farrington remarked that if school is set up in such a way that students feel welcome and that they belong and can succeed, then students are more likely to achieve. That ideal, many education scholars and now, Shaker administrators, believe is accessible through a mastery-based system.

Onaway Elementary School Principal Amy Davis emphasized that the strength in differentiated learning lies in its ability to address different students’ learning styles. She explains that the summative assessment, which measures what a student knows at the end of a unit, can be completed through several mediums.

“We like to make it differentiated so that everyone can do it on their own level,” said Sanya Godbold-Bell, Onaway’s IB Coordinator and a second grade teacher. “Some kids will make huge posters and sing songs and some kids will just orally tell what they learned. That’s all fine with us.” She spoke in conjunction with Davis.

“It’s pretty open-ended. Then we give [students] a rubric so that they know what they’re looking for and it’s not a surprise,” Godbold-Bell said.

In the summative assessment, Onaway is looking for mastery. At the elementary level, it’s easier to allow ample time for reassessment and additional chances.

“These are the building blocks of the rest of your educational career, so if you are not getting it here, we have a problem,” said Davis.”So we have a lot of support . . . They’re also with the teacher all day. If you didn’t get it at 9:30, we’re going to talk about it at 2 o’clock and maybe you’ll be redoing it the next day.”

“If a student gets a zero, they’re going to have to redo. I think because we don’t give grades, they have to master it,” said Davis. “We don’t let kids fall through the cracks. We have so much time to redo. There’s always time to redo.”

Mastery is the buzzword of new educational philosophies, as schools and researchers push for new measurement tools. Wormeli and Marzano describe mastery as demonstrating “a thorough understanding as evidenced by doing something substantive with the content beyond merely echoing it.” Mastery in education is when a student shows, through assessment, a project or other medium, that he or she knows, understands and can explain the material.

Students learn at different rates, according to Farrington. So some students might need more than one try to develop mastery of the material.

What concerns teachers is where to draw the line on redos, revisions and retakes.

“While I agree that we want to encourage students to do their work, much of what we do loses a lot of its learning value when it is completed outside the context of the actual unit,” wrote Pfeiffer. “I disagree with the premise that authentic learning takes place when students are just scrambling to complete paperwork for points.”

Wormeli and Marzano explain in their book how teachers can set guidelines and stipulations for second chances on work or assessments. The provisions he notes require students hold themselves accountable and that teachers set expectations for such opportunities. He notes that parents should be involved, teachers mandate all work be done at their discretion, and “not allow any work to be redone during the last week of the grading period.”

The two authors set limits on how late the student can make up assignments of redo work. The SHMS policy contains such provisions as allowing students to complete work up until the week before the grading period ends. Pfeiffer believes this is not enough time to allow teachers to adequately reassess and grade many new assignments. With the current policy, teachers must accept all late work and only subtract up to 30 percent as a penalty.

“It places an undue burden on teachers to try to score piles of old work at report card time, when we are already scrambling to get current work graded in time for report cards,” Pfeiffer wrote. Because Glasner emphasized the elasticity of the document, Pfeiffer hopes this part of the policy can be amended.

Wormeli and Marzano also note that if a student performs worse on the second assessment, teachers should not “just admonish the student for not studying, and move on.” Perhaps the teacher may need to reteach, assess his or her lesson plan, question whether the first score was a “fluke” or “a valid indicator of mastery,” they write.

“The idea is that we’re not satisfied if your understanding is at the level of a C or a D or an F. We’re not going to then just move on from there,” said Farrington. “That’s not OK.”

Hutchings agrees that students should be given the second chance—“treated as adults would want to be treated.”

“There’s always a reason behind [the sub-par initial grade] and I think we have to be a little empathetic to that. The world gives second chances,” he said. “I mean, just think about that. Every adult, probably in your life, has had a second chance at some point.”

“Initially, [that] people might turn in less things right the first time will be really frustrating for teachers, but I think that if the message for the school as a whole is, ‘We’re really serious about your learning and we’re investing in doing this because we care what you’re learning,’ and shift the emphasis to what you’re learning and not what grade you’re getting, then over time students under that system respond to that,” she said. “It’s a culture shift.”

Ledford, however, disagrees that the world always gives second chances. “If you fail the bar exam, you can’t take it again for six months,” he said. “Do you think the law firm will hold your job for six months?”

Yet Hutchings maintains that he, for example, gives second chances to his staff. For instance, he said, he does not fire someone for turning in something a day late.

Griffith admitted that deciding if a student is giving the necessary effort to be allowed another chance is not easy. “The avoidance of this question though, to me, is unacceptable,” he said. “I think what happens is, because this balancing act is hard, I think what people tend to do is go to either extreme.”

“So if you kind of get it, that’s not enough,” said Farrington. “I think it sends the wrong message to kids that you can pass at that level.”

However, Hutchings believes students who put forth minimal effort have reasons for doing so besides laziness.

“There are a number of different reasons why students fail classes,” said Hutchings. “Most students don’t just wake up and say ‘I’m not going to do anything.’”

It follows, then, that students should always be allowed another opportunity. “Sometimes I used to hear the comment ‘We’re not preparing them for the world,’ ” said Hutchings.

“So I feel like, the world is a forgiving world, and it’s not just so cut and dry. Police officers even give you second chances,” said Hutchings. “The Supreme Court gives you second chances. You go into a courtroom, they sometimes give you a second chance — you get probation you don’t go to jail, you know? So I think that we need to practice that.”

Pfeiffer, on the other hand believes that teachers’ obligations are not just to get students to complete the assignment, but to do it for a deadline.

“Part of our obligation as teachers is preparing students for their future, and I do not think that this particular late policy accomplishes that,” said Pfeiffer. “I’d like to see the authority returned to teachers to set reasonable red-line dates (which in my case, would coincide with the end of that particular unit.) If we are truly striving for mastery, then the grades should reflect that, rather than a student’s ability to fill in a lot of blanks on worksheets at the last second.”

While the high school does not have a set grading policy as of this article’s publication, Griffith has been pushing for teachers to allow more retakes, redos and revisions. Furthermore, he has attempted to make zeros in the grade book anomalies. He hopes to incorporate those ideas, and some from departments’ grading policies that he has reviewed, into a uniform high school grading policy.

“Our intention this whole year is to keep talking about this and then hope as an outcome for the year to come to a more standard sense on those kinds of things,” said Griffith. “Try to standardize where it is reasonable to do. We would then have a policy, not as lock-step as the middle school’s.” The standards Griffith is most concerned with involve redos, retakes and revisions. However, he believes certain non-academic, non-curricular or behavioral matters shouldn’t be in grading policies.

“There’s extra points for things like Kleenex and tissues and extra points that have nothing to do with the mastery,” said Griffith. “If the grade is supposed to be about mastery and where you are in terms of the standards and the content, then tissues and things probably don’t belong in there.”

Furthermore, Griffith believes that even if the same course is taught by different teachers, the expectations and measurements of completion and mastery should be the same. “An ‘A’ should be an ‘A’ should be an ‘A,” he said. “We should have an established understanding of what high quality mastery is. What’s really rigor.”

Yet he doesn’t believe the high school can have “one grading policy that captures the exact process for how those are each graded.” With such a range of course offerings, it’s not possible to have something as cut-and-dry as the middle school’s policy. Griffith remains confident that a set of standards regarding the broader tenets of grading is possible, however.

“If you have the fundamentals that we all believe in philosophically when we’re grading, you have the ability for each department or subgroup within the departments to come up with something that’s reasonable, that’s appropriate and that meets those expectations.”

Within that philosophy is the expectation students will be allowed second chances. “A redo [or] a retake means you already did it the first time. Why wouldn’t you do it again? The question there is gauging mastery . . . That’s back to the question of rigor. Why wouldn’t I challenge you to do it again?” he said.

“Learning is all about choosing to put forth effort, and if we’re not putting forth this idea, it’s only the A kids who well in this system [and] have the structures in place that are based on mastery instead of one-shot deal to succeed,” Farrington said.

However, revisions, redos and retakes mainly fall under the formative category in the grade’s calculation. According to the middle school’s policy and many individual high school policies, grades are weighted between formative and summative assessments of mastery.

Glasner believes the weighting of summative versus formative assessments was 60-40 at his previous school. He cited the difference between the breakdown at his previous school versus SHMS as “a function of where this schools is at versus where my last school was at.”

At SHMS, the breakdown between formative and summative is 65-35, which Glasner said is a better system.

Although the system may turn out to help students achieve greater success in the long run, for now, Sears wonders why there was need for a policy that contains such allowances on plagiarism, late work and redos in the first place.

“You really have to ask yourself, why was this policy put in place in the high school and the middle school? And it’s because not everybody’s doing their work,” Sears said. Part of the policy is for “practical” purposes, he said, and like Farrington he believes that the school has to make students feel like they can succeed. “Who’s taking action to help kids who are struggling in school after hours. Is anybody? We have some tutoring centers, but I don’t know,” Sears said.

Sears hopes the policy will encourage students to complete their work because they feel like they have another chance.

Friedman-Romell agreed, believing the policy will help students. “The new policy helps some kids pass classes who are struggling to turn in work,” she said. “I predict this year will have a high grade-wide GPA than any other year at SMS.”

However, “the problem I have is more, if they’re not doing any homework, they’re not building the skills they need for this level or the next level,” Sears said. “So yeah, we get them through school, but how does that really set them up for success later on?”

As for the policy’s practicality, Sears said, “we don’t have the resources to make 80 seventh graders repeat seventh grade. There’s political and economic reality to this policy. We need to get kids through school and graduate.”

Sears believes skills and knowledge should be at the forefront of any school policy, but that under this new policy, “maybe that takes a back seat.”

“We can’t have 20-year-olds at the high school” or the equivalent at SHMS, he said.

Academic Dishonesty

The higher in academia a student ascends, the tougher the standards on academic dishonesty become.

Scholars and university professors expect that students understand plagiarism and what constitutes cheating.

While Professor Ken Ledford of Case Western Reserve University expects this comprehension, he acknowledges that his students come from different backgrounds and have experienced different instruction about plagiarism. So he outlines the definition of plagiarism in his syllabus, adapted from Professor Vernon Lidtke of Johns Hopkins University.

“Plagiarism covers a multitude of sins. It involves the theft of words, ideas or conclusions from another writer,” Ledford’s syllabus states. Yet it doesn’t have to be intentional, so Lidtke concludes that “The safest rule to follow is: When in doubt, footnote.”

In the middle school, where students are younger and perhaps more ignorant of plagiarism, the new grading policy specifies how teachers must treat instances of academic dishonesty. It states that “the teacher should conference with the student, reach out to the student’s parent/guardian and provide the student with an opportunity to make up the assessment.” It then specifies that “Points may be deducted on the final work product, up to 30 percent of the grade.” Students who do not revise or re-attempt the assignment are to receive a 55 percent, 10 points higher than the base grade of 45 percent. The base grade of the middle school policy mandates that the lowest grade given for any assignment, including late or missing work, is a 45 percent.

This 30 percent reduction, however, can be interpreted two ways. It could be considered a deduction of 30 points from a top score of 100 on the redo. It could also be interpreted as a loss of 30 points from, for example, an 84 percent received on the revision. According to Glasner, no matter what, the student cannot receive below a 45 percent. For example, if a student received a 65 percent on a revision of a plagiarized paper, deducting 30 points would give them a 35 percent, but with the middle school base grade, the student would receive a 45 instead.

This lack of clarity in the policy is deliberate, according to Glasner. “I’ll be honest, I left that language intentionally vague,” he said. “I wanted to give teachers a year to kind of figure some of that stuff out for themselves and kind of see what makes sense.”

“If it was me in my classroom, I would give the student full credit,” Glasner said. He reasons that if the student redid the assignment, he or she has demonstrated mastery. This mindset, however, requires a shift in thinking across the board, Glasner said.

Middle school English teacher Erika Pfeiffer has ambivalent feelings about the grading policy’s stance on academic dishonesty.

“It has been my practice in the past to take strong and decisive action against plagiarism (as in fully documenting proof of the offense, giving a zero on the assignment, and informing parents immediately) so that students understand its seriousness; my attitude is, be honest with the kids and go through the growing pains now, while it hurts less — that stuff will get you kicked out of college!” Pfeiffer wrote in an email interview.

The middle school policy, however, does not entirely align with those of higher education institutions and reflects younger students’ less sophisticated understanding of plagiarism.

Like many college professors, Ledford assigns students an F for a plagiarized paper that will then “be calculated as a zero (‘0’) into the student’s final grade.” Such instances are reported to the dean of undergraduate studies at CWRU. This is similar to the sanctions at the University of Chicago, where Farrington is an assistant professor and research associate in the School of Social Service.

The University of Chicago forbids anything that could undermine their standard of research, stating on its website, “We believe it is contrary to justice, to academic integrity, and to the spirit of intellectual inquiry to submit the statements of ideas or work of others as one’s own.”

Farrington believes that educating students about academic dishonesty is essential to combating it.

“I think the general idea of trying to figure out if a student made a mistake versus if they were actively cheating, or didn’t understand what they were doing was plagiarism versus actively copying something — those are important questions,” Farrington said.

Ledford also mentioned the similar honor codes of Princeton University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Very traditional honor codes—you cannot lie, cheat or steal, and they do not tolerate those who do, right?” said Ledford. “So plagiarism is lying. If you are accused of plagiarism in one of those schools, this honor offense goes to a student-run honor system and there’s a trial in front of students.”

“No matter what the professor does in terms of the grade in the course, you still will have to answer to the honor court system, and that goes on a separate part of your transcript,” said Ledford. “And you could be separated from the university permanently, temporarily [or] have other consequences.

Furthermore, Ledford noted that any breaches to the honor code go on a student’s record, and a dean writing a letter of recommendation to law school or graduate school would have access to that information. Ledford said that when he writes recommendation letters for students to law school, he answers this question: Does this person have adequate character to be admitted to the bar?

“At the University of Virginia, there’s a single sanction in the honor system. If you were found guilty, you were expelled and you could never come back,” Ledford said.

CWRU’s academic dishonesty policy states, “All forms of academic dishonesty including cheating, plagiarism, misrepresentation, and obstruction are violations of academic integrity standards” and are subject to university sanctions that escalate with subsequent violations. All violations are recorded in the student’s judicial record.

Ledford is concerned that under a policy such as the middle school’s, students could redo assignments they originally plagiarized or completed dishonestly, and admissions officers would be none the wiser.

“I would like somehow to know, if I have a student from Shaker in my classes, if there is in that Shaker student’s background a plagiarism accusation,” he said. “That would be invisible to me if they wound up making a C. It would just be rolled into an unusually low grade.”

“I’m all in favor of second chances in somebody’s college career, but not in my class,” said Ledford. “It would make me very uncomfortable if I could establish someone committed plagiarism in my class.”

He adds that with tools such as Turnitin.com, plagiarism is easy to discover. “Just take a 10-word sentence and put it in quotations and Google it. If they’ve copied it, it will show up.”

While Griffith, too, believes in second chances, he agrees with Ledford that students should not have the same opportunity to earn full credit if they redo an assignment.

“I have a very hard time with the concept that they could turn around then and get an A if they’ve made the choice and I believe they’ve made that choice, like cheating on a test or plagiarizing a paper,” Griffith said. According to the policy’s current notation, when a student redoes an assignment she plagiarized, she could only be deducted up to 30 percent and thus could still receive an A for the assignment. However, because Glasner, SHMS’s principal, left the language intentionally vague, that is, at the teacher’s discretion — the teacher just cannot give a student a grade below the 45 percent base grade.

“At the same time, I want to say this: we are compulsory education. Our job, in part, is to also help students become understanding of the expectation of what it means to be a good student and all of those elements. College is not [compulsory]; it’s a choice. I think they should be held to that higher standard,” said Griffith. “You’ve made a choice to come to a college or university and that’s expected there.”

“Students should have learned what plagiarism is and how to avoid it long before they seek and obtain admission to a university,” Ledford writes in his syllabus.

With the mastery-based grading at the elementary schools, students are expected to know what plagiarism is by fourth grade, according to Davis, Onaway’s principal. Sonya Godbold-Bell, Onaway’s IB coordinator, qualified this by the students’ ages.

“We don’t really say that they’re plagiarizing cases,” said Godbold-ell. “They’re just times to learn. [Students are] not trying to do it to pass it off to the teacher to get this grade. They really didn’t understand that ‘I can’t just copy.’ They don’t get the citing sources right now, so it’s not really plagiarizing for us. Just say it in your own words.”

Davis and Godbold-Bell agreed that students will understand the concept by the fourth grade, however.

“They will know what [plagiarism] is by fourth grade for exhibition because their parents have to sign a form and they have to sign a form that during this huge research culminating activity that they will not plagiarize anyone else’s work and then they talk about what it is,” said Davis. “And that’s an IB thing.” Exhibition is a creative project students complete in the fourth grade. Students work in groups to write their own unit of inquiry, and it could be compared to a capstone project.

Social studies teacher Elizabeth Plautz, who is teaching only IB and AP economics classes this year, believes plagiarism might not carry the weight it once did. “I think that the whole notion of plagiarism is getting warped,” she said. “As a teacher of an AP course, I have to be mindful it’s a college-level course.”

Pfeiffer agrees. “Better to have a hiccup on a report card in 8th grade and learn the lesson than to face the consequences at the university level,” she wrote.

“I understand the thinking behind the new policy,” Pfeiffer wrote. “It is commesurate with the efforts to encourage students to do their work and not blow projects and assignments off as ‘lost causes.’ It’s also in line with the new ‘no-zero’ policy. I think we just have to be very careful to communicate the realities of what could happen if such habits continue into the future.”

Griffith said, “Our intention here is to teach. So our motivation in anything here that we’re doing, we really should have a focus on teaching students about accountability, teaching students about self-discipline, teaching students about self-control.”

“Do we expect that in perfection from everybody at this stage in their lives? No,” he said. In college and the professional world, “That’s expected to be now in place. And therefore their consequences are much more immediate and severe.”

Ledford argued that academic dishonesty threatens the relationship between teacher and pupil. “If you plagiarize, you’ve fallen in my esteem, and on some level it’s irretrievable,” he said.

“We could penalize students for academic dishonesty, but there has to be an education that comes along with it,” said Glasner.

“It’s about education and teaching students what academic dishonesty is,” said Glasner. “Why it’s so important to avoid it, what consequences of academic dishonesty are in college, careers, and on the positive side, how do we remain academically honest? How do we cite our sources? How do we give credit to the information or knowledge that we’re using? How do we conduct research appropriately?”

“So yes, it’s important to penalize students for academic dishonesty, and the grading policy accounts for that, but it’s also for, that at the end of the day, students have completed an assessment,” Glasner said.

Common Core and the National Shift of Mind

Hutchings reasoned that the shift towards mastery-based grading follows logically from Shaker’s practice of not declaring class valedictorians or publishing lists of colleges acceptances beside students’ names.

Superintendent Gregory C. Hutchings, Jr. speaks during a meeting. “You know, we’re already great, but wha’ts going to make us even greater is making sure that 100 percent of our students are held accountable for completing their work,” he said.

“At Shaker we don’t have a valedictorian at Shaker Heights High School because our focus really needs to be on are you students really being prepared to go out into the world to take on whatever task they choose–whether it’s going off to college, or going into a career or joining the military,” Hutchings said.

Yet, according to Glasner, for a high school to shift to a mastery-based grading system, it could take three to five years. Furthermore, the constraints of college prerequisites of grades and GPAs limit how schools make such an adjustment.

Although the high school has not made the adjustment, Hutchings said “that’s something that’s definitely on the table.” He said that he wanted to wait to hear from teachers and administrators about such a policy change, saying “The sky is the limit.”

However, Hutchings said, “I think it will over time shift more so into a standards-based reporting [of mastery].”

In praise for a mastery-based system, Hutchings said, “grades, to me, sometimes, they may not tell the full story of what a student knows and what they don’t know.”

He cites an interaction with a parent whose child received an A in a course. However, when the parent quizzed the child about the course’s curriculum, the student couldn’t answer. A mastery-based system, Hutchings argued, will identify exactly what a student can and cannot do or understand. “I think that we should try to focus more on mastery of specific standards versus grades,” he said.

The decision contributes to a growing consensus that students and teachers have become “bean-counters,” as Griffith phrased it. In other words, points have become the teacher’s key motivational tool. Factored into grades, they can determine a student’s future.

Hutchings emphasized that the overarching goal is to help students succeed in and beyond high school. “That is our goal – to be prepared to go to college, to start a career, to go into the military,” he said. “To do that, you really have to have some guidelines that make it possible for kids to be successful.”

To accomplish this goal, the administration has laid out their goals broadly–under which fall an adjustment in grading policy or academic supports to help a student flourish.

“One of our core values in our five-year strategic plan is ‘Students will succeed.’ It doesn’t say students can, students might, it says students will succeed,” said Hutchings. “And a part of that is making sure we put parameters in place and we put opportunities in place for them to actually attain that.”

Griffith considers redos, revisions and retakes as ways to engage a student beyond the grade and into the learning process. “If I’m looking at you as a student, giving you feedback, are you really present?” he said. “Are you really coming to the table with your best effort? And if you are, let’s roll up our sleeves and work together. And if you’re not, how do I motivate you to bring more?”

“We’ve set a system where grades drive a whole system,” said Farrington. “There are all kinds of reasons why students should learn.” Schools should use different motivational tools that emerge from a different grading system, she said. In the schools that have made the switch, “ . . . You have to actually have meaningful work, trying to solve the problem with the food pantry and in our neighborhood, and what motivates us if we’re doing work we care about and we won’t want to let people down.”

Motivation is key to shifting successfully to a mastery-based system, Farrington said. She reasoned that students have been this,’ and they have used points as the major “socialized” to respond to grades. “ ‘I do work because I care about my grade,’ and so teachers have used that really heavily . . . ‘You’re gonna get points off if you don’t do this,’ and they have used points as the major motivational tool, and that ruins the whole enterprise of school,” she said.

“Schools are the only institution where kids are really getting graded and that’s the motivation,” said Farrington. “Grades are just such an artificial thing. If you remove that and you have multiple opportunities to do it, and there I think if all we change is the grading system, then [not completing quality on-time work] is exactly the natural behavior because that’s the system we’ve cultured people in.” Farrington believes that a shift to mastery-based grades will only be successful if there is a shift, too, in how schools motivate students to learn.

Ledford, of CWRU, said that while eliminating grades would be ideal, in America it’s a “pipe dream” because the “United States is a hyper-competitive society in which we want this fetishized system of grades.” Ledford worries that certain skills have been lost, such as the ability to read and write long-form pieces. “The one thing I think is lost is long-form writing is dead, and they’re wrong because ideas are complex and human life is complex and it takes lots of words to articulate the complexity of human life,” he said. “People still read books and books are much longer than this.” However, he does believe that there are other motivators outside of grades.

“In the absence of grades, what students garner is the esteem of their teachers,” said Ledford. “Think back to Socrates on the stoa of Athens. He didn’t give grades — what he gave was his approval and his esteem to his pupil. They knew they would be better people; [they would]learn partly for themselves and learn for their professors’ esteem.” (A stoa is a covered porch of ancient Greek design.)

Farrington also noted that with Common Core standards, it doesn’t make sense that grades don’t correlate with standards. “It’s ironic that we’ve have had standards and that’s been a primary driving force, but your grades have nothing to do with whether or not you’ve met those standards,” Farrington said. Farrington further stated the disparity between standardized test scores and grades. “Scores have nothing to do with grading,” she said. “Grading has a life of its own that has nothing to do with the primary education doctrine of the last 20 years, and the move towards mastery grading is in line with a national move.”

“If these standards are what we care about, [then] let’s grade people about whether or not they’ve met the standards . . . It’s happening all over the country and I think that over time more and more places will do this and [it will become] less of a fad and more of a ‘Let’s grade people on whether they’ve met the assignment,’ ” Farrington said.

Ledford, however, warns that teaching to the test, as some call it, is damaging to a student’s college preparation. “[Students] come in, and they’re worse than ever since the move to high-stakes testing,” he said. “The distortion that [testing] imposes on the curricular time in school has been to the student’s detriment. They are memorization machines rather than critical thinkers. They think that learning is compiling facts to regurgitate, and I don’t care about that. I care about being able to put two ideas together and analyze.”

Similar to Griffith and Hutchings, Farrington noted that the ideal end point would be a system with no grades at all, though that is very difficult to achieve. “What if there were not grades at all? What would happen?” Farrington said. “Some people would think the whole thing would totally fall apart and the only reason [students] have to [do work] is because they get a grade.”

She blames the entrenched 100-year-old American school system, whose design — the subject of her book “Failing at School: Lessons for Redesigning Urban High Schools” — subjected some students to inherent failure. “We’ve inherited a structure and a system that’s been around for over 100 years, and it was designed for a different purpose when only 5 percent kids went to high school and only 1.5 percent of kids graduated,” Farrington said. Because the public was concerned with wasting taxpayer money, they encouraged a system that failed many students in the interest of giving only “the best and the brightest” a substantial education, she said. The rest could find decent jobs without a high school degree.

Many problems schools face today are linked to that history, she said. “We have the same system and same policies and practices . . . and what ends up happening is it really stratifies achievement,” said Farrington. “The kids who do really well in school excel in that system, and then there’s everybody else, and that could be 90 percent of the people and it ends up that that kids don’t really learn well.”

Davis shares that belief. She highlighted aspects of mastery-based learning in the elementary school that compel students to learn. Yet, motivating children at such a young age is simple. Students are “intrinsically motivated” because they want “to please,” she said. “Because it’s so creative, there’s access for all levels of learners,” said Davis.

“Nobody feels like they can’t do it, because it’s creative. Now, when you get into the standards, you do have to show mastery, and they’re very motivated because of that.”

“They don’t need points, they don’t need grades,” said Davis. “They’re motivated by the process.”

The change in grading requires a change in students,’ teachers’ and administrators’ mindsets, according to Glasner. Glasner’s previous high school, where he was principal, did not employ mastery-based grading — although it has a grading policy very similar to the middle school’s new policy — but some schools in the Urban Assembly conglomeration have made the change.

“I think it really requires a shift in thinking across the board,” said Glasner. “The purpose of work across assessments is to demonstrate mastery. We’re not doing it just to complete it but to learn it. It’s evidence that we have mastered a learning perspective. If you don’t do something you will still fail; an F is still an F.”

Glasner said that two schools in the Urban Assembly, The Maker Academy and The UA Institute of Math and Science for Women use mastery-based grading. Established in fall 2014, The Maker Academy is founded on this grading philosophy. The school’s website states that mastery-based grading enables the school to meet Common Core standards as well.

Meeting the Common Core curriculum standards while satisfying the requirements of being an MYP district and IB district mesh nicely in some areas but clash in others. John Moore, science teacher and the high school’s IB MYP coordinator, believes that the IB curriculum enhances achievedment under Common Core standards.

Part of being an MYP district mandates that Shaker add units of study each year, about two per annum, so “by 2017 every unit is going to be an MYP unit,” said Moore. “Every unit is assessed with one of these rubrics. So it’s part of any grading policy–this is a necessary part–because we’re an MYP district, and so as we add more units, you’re going to be seeing [the rubrics] more and more and more. The units that we currently have are being assessed with these rubrics and eventually that will be all eight or nine or 10 or however many units a teacher covers in a year times eight subjects, times grades 5-10, so that’s a lot. And the idea is that everyone’s used to these rubrics then. It becomes part of what we do.

“So what MYP has done is not necessarily content-based at all, but much more skills-based which make a nice connection with the Common Core,” Moore said.

In other words, the IB rubrics articulate skills a student should master, whereas the Common Core standards state exactly what the student should know. For example, an IB MYP science rubric states that the student should be able to “explain scientific knowledge.”

The teacher would then look at what students need to know under Common Core standards for that year — properties of matter, for example. Expressed through the MYP rubric, that Common Core standard specifies that a student should be able to explain the properties of matter and why they are important, according to Moore.

Griffith said that the MYP rubrics are challenging to convert into letter grades, however. Because the MYP assessments were never intended to be converted to a 100 point scale, they are not as accurate as the initial grade once converted.

A committee comprising high school faculty and adminsitration is collaborating to develop a standard grading policy for the high school, and, like the middle school’s policy, it will address conversion of MYP grades to the traditional scale.

The district’s effort to standardize grading is not mandated by the state, although use of Common Core standards is.

“The state of Ohio does encourage school districts to adopt curriculum that aligns with the new learning standards which include Common Core standards in English and math,” said John Charlton, Ohio Department of Education’s associate director of communications.

“We believe that while a district may have an overarching policy on grading, each teacher should be given some flexibility to make their own grading decision that again meet the needs and priorities of the students in that class,” Charlton said.

Moore said that he thinks the MYP standards tie “beautifully with trying to push young people to deeper and deeper levels of thinking,” and coupled with the Common Core State standards, will play a role in any grading policy in the high school. He thinks MYP pushes teachers to be creative. “I think it’s all positive change. That way it can be revolutionary for our assessments.”

Because rubrics are central to IB and MYP, they will be become essential to grading policies and teachers’ unit designs. According to Moore, the policies must be easily accessible for students online, handed out in class or posted on the wall.

“The goal behind this is that they say by the end of the unit, I am going to have to be able to explain this knowledge, here’s what knowledge that is. And the rubric does that,” he said.

As for the impact of the shift, Moore doesn’t belittle the hardship on teachers. “It is so complex,” Moore said. “It’s throwing teachers through a loop . . . but change is not always bad.”

According to Farrington, schools nationally are moving to mastery-based system to achieve greater success across the board.

According to Hutchings, the year before he came to Shaker schools, as director of pre-k through 12th grade initiatives in Alexandria City Public Schools, he worked on a committee to design mastery-based grading for the elementary schools. Shaker already had a similar program.

Assessing Change

With only a quarter and a half of grading under the new middle school system, the policy’s impact is unknown. The district’s strategic plan outlines the timeline for changes to district grading policies. This year requires only the audit of policies in all buildings. By 2018, all buildings will employ a standardized grading policy. According to Hutchings, the process in each building will be a collaborative one.

Leo Izen | Feb 4, 2015 at 1:27 am

So… you’re telling me that I could copy an entire paper from the internet verbatim, have to redo it because it’s plagiarized, and then not redo it and receive a 55 percent? Something seems wrong about that. Especially since I’m not even guaranteed to get 55 if I do the assignment poorly but originally.

Second, it’s not accurate to say that “A 100-point scale with unequal intervals is ‘mathematically wrong.'” Do you know why it’s uneven, because someone who gets 55 percent on a test does not understand the material well enough to pass. A “C” is “average,” as in, not spectacular but passing. That correlates well with about 75 percent in high school or middle school.